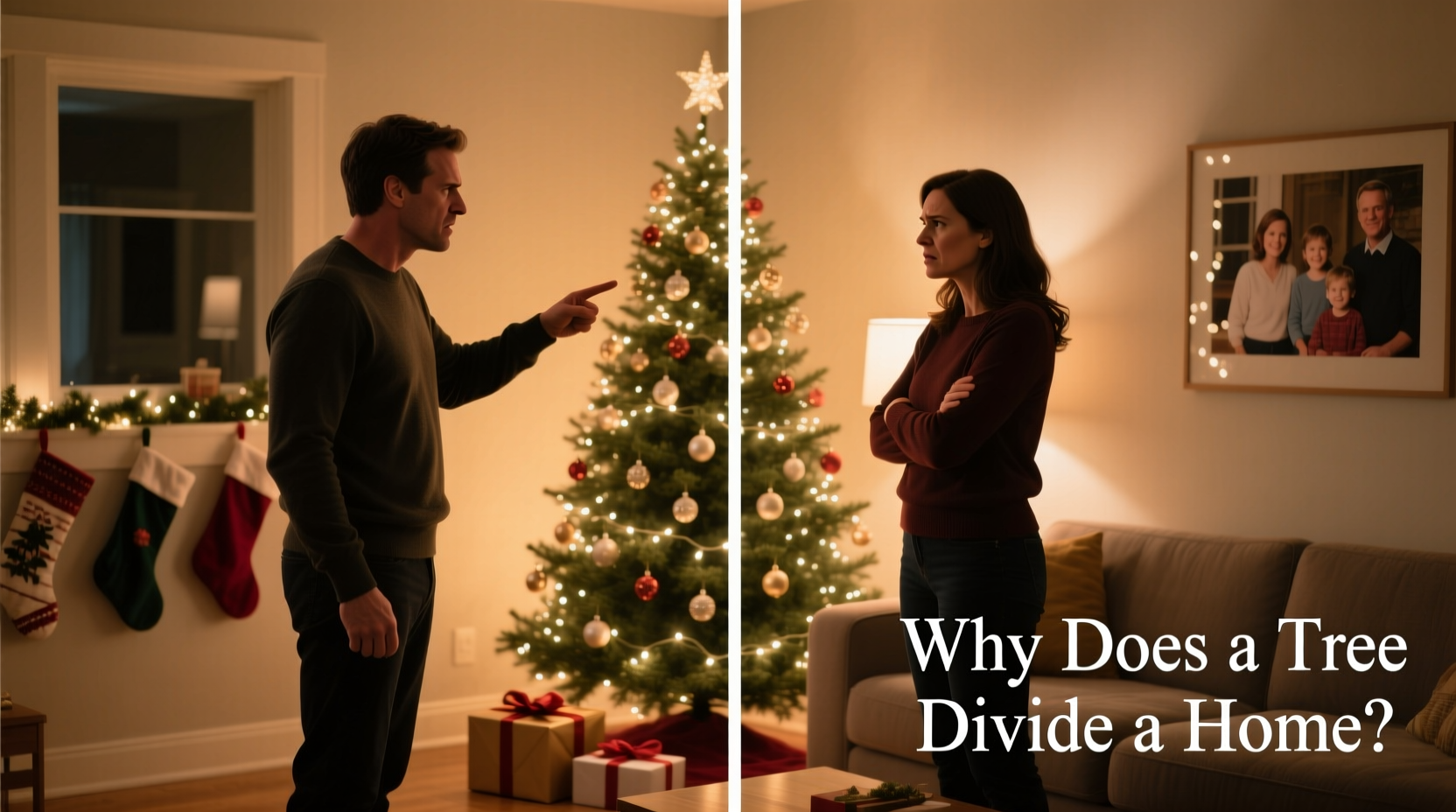

At first glance, arguing over where to put a Christmas tree seems trivial—almost comical. Yet therapists report that holiday-related spatial disagreements rank among the top five recurring conflict triggers in long-term relationships. What appears to be a simple logistical decision often surfaces deeper tensions: competing childhood traditions, unspoken expectations about home aesthetics, divergent definitions of “centerpiece” versus “background,” and even subtle power dynamics around whose family customs “count” more. These arguments rarely stem from the tree itself—but from what it symbolizes: belonging, memory, authority, and emotional safety in shared space. Understanding this layer is essential—not to dismiss the friction, but to transform it into an opportunity for mutual understanding.

The Psychology Behind the Pine Needle Standoff

Christmas tree placement isn’t neutral. It’s one of the few annual decisions that physically reorganize domestic hierarchy. When Sarah insists the tree go in the bay window—where her mother always placed hers—it’s not just about light reflection; it’s about continuity, identity, and honoring a lineage she associates with warmth and stability. When Mark prefers the corner near the fireplace, he may be anchoring the season to his own childhood living room, where carols played on a scratchy record player and hot cocoa steamed beside crackling logs. Neither preference is irrational. Both are emotionally encoded.

Neuroscience supports this: the hippocampus—the brain’s memory and spatial navigation center—activates strongly during holiday rituals. Familiar placements trigger positive affective responses tied to safety and nostalgia. Disrupting them can provoke low-grade anxiety, misinterpreted as “stubbornness.” Clinical psychologist Dr. Lena Torres explains:

“When partners argue over the tree’s location, they’re often defending neural pathways built over decades. It’s not about square footage—it’s about whether their internal map of ‘home’ still feels valid in the shared space.”

This becomes especially charged when couples blend households, relocate, or navigate blended families. A tree placed where stepchildren’s stockings hang may feel like inclusion to one spouse—and erasure to another whose traditions were sidelined during prior holidays.

Five Common Root Causes (and What They Really Signal)

Below are the most frequent placement disputes—and the underlying needs they reveal:

| Surface Argument | What It Often Represents | Unmet Need |

|---|---|---|

| “It blocks the TV/view/window.” | Fear of losing functional control over shared leisure space | Autonomy, predictability |

| “It doesn’t look right there—it ruins the flow.” | Anxiety about aesthetic coherence reflecting personal identity | Recognition, self-expression |

| “My parents never put it there—why start now?” | Grief over lost continuity or fear of cultural dilution | Belonging, intergenerational connection |

| “We paid for this stand—it only fits in the alcove.” | Disagreement over resource investment and decision-making authority | Respect for contribution, fairness |

| “The lights reflect weirdly on the glass.” | Sensory sensitivity or neurodivergent processing differences | Physical comfort, neurological safety |

Recognizing these patterns prevents escalation. Calling someone “overly picky” shuts down dialogue. Naming the need—“It sounds like having the tree visible from the front door matters because it’s how you felt welcomed as a child”—opens space for collaboration.

A Step-by-Step Compromise Framework (Tested in 12 Real Couples)

This isn’t about splitting the difference. It’s about co-creating meaning. Follow these steps before measuring tape comes out:

- Separate the Symbol from the Spot. Each partner writes down: “Three words that describe what the tree represents to me at Christmas.” Compare lists. Notice overlaps (“joy,” “family,” “peace”) and distinctions (“tradition,” “surprise,” “quiet”). Anchor future decisions in shared values—not just coordinates.

- Map the Room Objectively. Sketch the living area (no scale needed). Note fixed elements: doors, windows, outlets, traffic paths, furniture anchors, and lighting sources. Circle three zones that meet *minimum* criteria: safe (away from heat vents), stable (solid floor), and visible (seen from at least two seating areas).

- Assign “Non-Negotiables” (Max Two Each). Examples: “Must be within 6 feet of an outlet,” “Cannot obscure the bookshelf where our kids’ ornaments live,” “Needs direct morning light for photos.” Eliminate zones violating either person’s non-negotiables.

- Prototype & Photograph. Use a tall potted plant or ladder draped with green fabric to simulate each remaining option. Take identical photos from key vantage points (couch, entryway, dining table). Review together—without commentary—for 60 seconds. Then share first impressions: “This one makes me feel…”, “I notice my eyes go to…”

- Co-Design the Context. Once a zone is chosen, jointly decide how to enhance it: new rug under the tree? Rotating ornament display schedule? A dedicated “tree-lighting ritual” with specific music? Shared authorship of the environment reduces territorial defensiveness.

Real Example: The Corner vs. Center Dilemma in Portland

Maya (38) and James (41) argued for three years over tree placement. Maya grew up in a New England farmhouse where the tree stood centered beneath a wide staircase—a focal point for gift-giving and caroling. James, raised in a compact Seattle apartment, associated trees with cozy corners beside reading nooks, where the scent of pine filled intimate spaces. Their Portland bungalow had both features: a dramatic central hearth and a sunlit bay window nook. Every December, tension spiked during setup, culminating in last-minute compromises that left both feeling unseen.

Applying the framework above, they discovered their shared non-negotiables: proximity to the fireplace (for ambiance), visibility from the kitchen (where they cooked together), and space for their daughter’s handmade “elf village” beneath the branches. The center hearth met all three; the bay window blocked kitchen sightlines. But instead of accepting the center, they co-designed: they installed soft LED string lights along the mantel to echo the “glow” Maya associated with her childhood staircase, and added a deep armchair with a fleece throw to the hearth’s left—creating James’s cherished nook *adjacent* to the tree, not separate from it. Their daughter now places elves in both spots. The tree stands centered—but the *experience* of it is layered, inclusive, and intentionally woven.

Practical Compromise Strategies That Work

When values align but logistics clash, these tactics bridge gaps without resentment:

- The “Rotation Rule”: Alternate primary placement yearly (e.g., center one year, window nook the next), while keeping secondary elements consistent—same lights, same tree skirt, same playlist. Predictability in ritual eases transition.

- The “Zoned Tree”: Use a slim, tall tree (e.g., 7' x 2') in tight spaces, or a tabletop version on a console table near a doorway. This satisfies visibility needs without dominating open floor plans.

- The “Light-First Approach”: Choose placement based on natural and artificial light quality—not furniture layout. A tree lit by dawn sun or warm lamplight feels intentional, regardless of exact spot.

- The “Anchor Object”: Place a meaningful object (a vintage sled, a framed family photo, a ceramic star) in the chosen spot *before* the tree arrives. This psychologically “claims” the space as collaborative, not contested.

- The “Post-Placement Ritual”: After positioning, both partners add one ornament simultaneously—one representing heritage, one representing aspiration. This reinforces joint ownership of the symbol.

FAQ: Addressing Lingering Doubts

What if one partner genuinely dislikes Christmas trees altogether?

This shifts the conversation from placement to participation. Respect the boundary: offer alternatives like a living wreath on the door, a single branch arrangement on the dining table, or a “light-only” display using fairy lights in jars. The goal isn’t uniform celebration—it’s honoring each person’s authentic relationship with the season.

Can we use a fake tree to avoid the debate entirely?

Not necessarily. Artificial trees introduce new friction points: storage space, assembly time, realism preferences, and environmental concerns. The core issue remains—symbolic weight and shared meaning—not botanical authenticity. Focus on *why* a real or fake tree matters to each person before choosing.

Our in-laws weigh in every year—how do we hold our boundary?

Preempt it. Send a warm, unified message early: “We’re creating our own tree tradition this year—can’t wait to share photos!” Then, when opinions arise, respond with appreciation (“Thanks for caring so much about our holidays!”) followed by gentle clarity (“We’ve settled on what feels right for our little family this season”). Consistency disarms pressure.

Conclusion: Your Tree Is a Mirror, Not a Milestone

The Christmas tree isn’t a decoration. It’s a temporary monument to how two people negotiate love, memory, and space. Every argument over its placement is a quiet invitation—to listen deeper, name needs without blame, and choose curiosity over certainty. Compromise here isn’t about surrendering your history; it’s about expanding your definition of home to include both stories, side by side. When you finally step back and see the lights glow—not in the spot you demanded, but in the place you built together—you’ll recognize something more enduring than tinsel: the quiet strength of a partnership that chooses understanding over being right.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?