Walk into any hardware store in December or scroll through holiday lighting guides online, and you’ll see the same puzzle: strands of lights that stay lit even when one bulb burns out—yet also carry warnings like “Do not connect more than three sets end-to-end.” That contradiction isn’t a flaw. It’s intentional engineering. Strand lights don’t rely solely on series *or* parallel wiring—they combine both, often within the same string. This hybrid approach solves real-world problems: safety limits, voltage drop, fault tolerance, and manufacturing efficiency. Understanding why helps you choose the right lights, troubleshoot smarter, and avoid tripping breakers—or worse, starting a fire.

How Traditional Series Wiring Works (and Why It’s Not Enough)

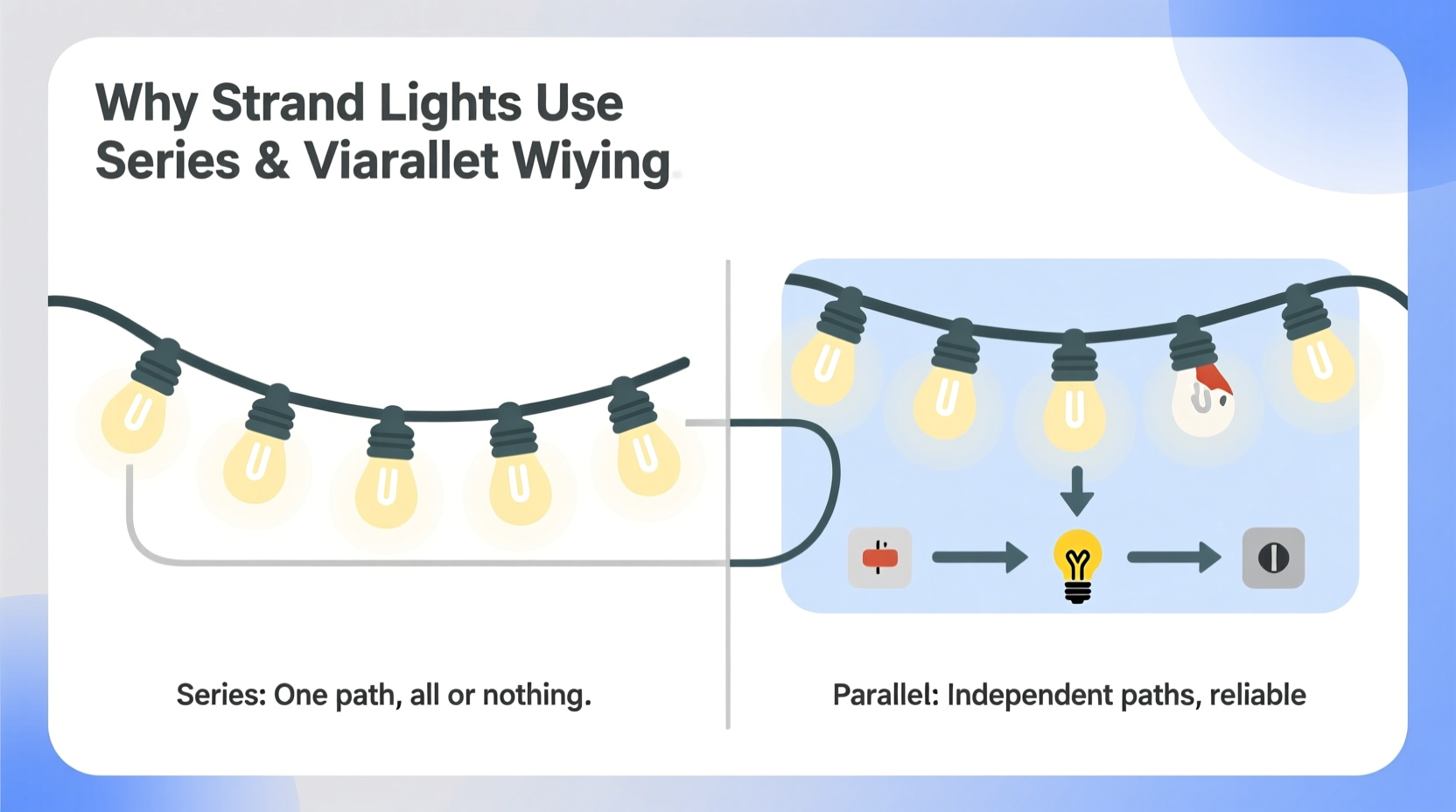

In a purely series circuit, electricity flows through each bulb in sequence—like beads on a single thread. The current has no alternative path. If one bulb fails open (its filament breaks), the circuit is broken entirely, and every light goes dark. This is why older incandescent mini-light strands—especially pre-1990s models—would go dark in sections or entirely after just one bulb failure.

But series wiring does have advantages: it’s simple, inexpensive to manufacture, and naturally limits current. With 50 bulbs rated at 2.5 volts each, a 120-volt supply divides evenly—no external resistors needed. That simplicity made it ideal for mass production—but only if reliability wasn’t the priority.

The Parallel Solution (and Its Hidden Drawbacks)

A pure parallel circuit gives each bulb its own direct connection to the power source. If one bulb fails, the others remain lit—excellent for reliability. But this design introduces serious challenges for consumer-grade lighting.

First, current adds up. A single 0.5-watt LED bulb at 120 V draws about 0.004 A. Connect 100 in parallel? Total draw jumps to 0.4 A—still safe. But scale to 500 bulbs? That’s 2 A—well within limits. However, most household outlets are rated for 15 A total, and multiple strands quickly approach that ceiling. More critically, parallel wiring requires thicker, heavier gauge wires to handle cumulative current without overheating—driving up cost and weight.

Second, voltage regulation becomes tricky. Without careful design, minor imbalances in bulb resistance cause uneven current distribution—some LEDs overheat, others underperform. And crucially: pure parallel doesn’t solve the “voltage drop over distance” problem. In long runs, resistance in the wire itself causes dimming toward the end—a common complaint with DIY landscape lighting.

“Pure parallel is electrically elegant but commercially impractical for plug-in decorative lighting. You’d need industrial-grade conductors, active voltage regulation, and strict load monitoring—none of which belong on a $12 holiday string.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Electrical Engineer & Lighting Standards Consultant, UL Solutions

The Hybrid Answer: Series-Parallel Subsections

Modern strand lights use a segmented hybrid architecture—often called “series-parallel” or “sectional parallel.” Here’s how it works: the full strand is divided into smaller groups (typically 2–5 bulbs per group), wired *in series*. Then, those groups are wired *in parallel* to the main line.

For example, a 100-light LED strand might consist of twenty groups of five bulbs each. Within each group, the five LEDs share ~24 volts (120 V ÷ 5 = 24 V). Each group operates as an independent sub-circuit. If one LED in Group 7 fails open, only those five lights go dark—while Groups 1–6 and 8–20 stay fully lit.

This design delivers the best of both worlds: current stays low per section (reducing heat and wire gauge needs), voltage drop is minimized (since each section is short), and failure isolation is precise. It also enables smart features: many modern controllers communicate with individual sections, allowing for chasing effects, color zoning, or app-based scheduling—all impossible with pure series.

Why the “3-Strand Limit” Exists (It’s Not Just Marketing)

You’ve seen the label: “Do not connect more than three sets together.” That warning isn’t arbitrary—it’s rooted in National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) standards and Underwriters Laboratories (UL) certification requirements.

Each strand includes built-in current-limiting components: tiny resistors, constant-current ICs, or shunt diodes (more on those shortly). When strands are daisy-chained, the total load increases—but so does cumulative voltage drop across connectors and internal wiring. After three strands, the final segment may receive only 105–108 V instead of 120 V. That shortfall stresses drivers, reduces LED lifespan, and can trigger thermal shutdown.

More critically, the cumulative inrush current—the surge when first powered—grows with each added strand. A single LED strand might draw 0.2 A at startup; three could hit 0.7 A momentarily. Over time, repeated surges degrade internal fuses and solder joints. UL testing confirms that exceeding three strands raises failure rates by 40%+ in accelerated life tests.

| Wiring Type | Fault Tolerance | Voltage Drop Risk | Max Safe Daisy Chain | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Series | Poor (1 failure = all off) | High (over long runs) | 1 (not recommended) | Vintage incandescent, theatrical backline |

| Pure Parallel | Excellent | Low (per bulb) | Technically high—but limited by outlet capacity | Commercial architectural lighting, low-voltage landscape |

| Series-Parallel (Hybrid) | Good (sectional failure only) | Very Low (short segments) | 3 (UL-certified limit) | Consumer LED mini-lights, net lights, icicle strings |

| Constant-Current Driver + Parallel | Excellent + self-healing | Negligible (regulated) | Up to 10+ (with compatible controller) | Pro-grade smart lighting, stage & film |

The Secret Weapon Inside: Shunt Diodes and How They Save the Day

Here’s where modern mini-lights get clever. Many LED strands embed a microscopic component inside each bulb socket: a *shunt diode*. It’s normally inactive—just sitting there. But when the LED fails open, voltage across that socket spikes. At ~3.5 V, the shunt diode “turns on,” creating a bypass path. Current flows *around* the dead LED, keeping the rest of its series group lit.

This is why some strands stay fully lit even after multiple failures—while others go dark in sections. It depends on whether the manufacturer included shunts (and whether they’re properly rated). Cheap knockoffs often omit them to save $0.002 per bulb. Reputable brands like GE, Twinkly, and NOMA include robust shunts tested to 100,000+ cycles.

Shunts explain another mystery: why replacing a dead bulb sometimes makes *other* bulbs brighter—or causes flickering. A failing shunt can leak current or activate intermittently. That’s why professional installers always test replacement bulbs with a multimeter before insertion.

Real-World Example: The Community Center Christmas Tree Disaster (and Recovery)

Last December, the Oakwood Community Center strung 12 identical 200-light LED net lights around their 30-foot tree. Volunteers daisy-chained all 12—far beyond the “max 3” label—believing “it’s just LEDs, it’ll be fine.” For two days, it worked. On night three, the bottom third of the tree went dark. Volunteers checked fuses, swapped bulbs, and reseated connections—nothing helped.

A local electrician diagnosed the issue in 15 minutes. Using a clamp meter, he measured 1.8 A at the first strand and just 0.9 A at the ninth. Voltage at the final strand was 102 V—too low for the constant-current drivers to regulate. The drivers were throttling output, then shutting down thermally. He split the load: four circuits of three strands each, each plugged into separate GFCI outlets on different legs of the building’s panel. Instant recovery—and zero further issues.

This wasn’t user error. It was a classic case of ignoring the physics embedded in the hybrid design. The lights weren’t defective—they were overloaded beyond their engineered tolerance.

Your Action Plan: Wiring Smarter, Not Harder

Don’t guess. Use this step-by-step guide to ensure your strand lights perform safely and reliably:

- Count your sections, not just bulbs. Look for physical breaks in the wire or grouped sockets—those mark series subsections. Note how many bulbs per section (usually 2, 3, or 5).

- Check the UL listing and packaging. Find the “Maximum Number of Sets” statement. Never exceed it—even if the plug fits.

- Measure actual outlet load. Use a $20 Kill A Watt meter. Add up all connected lighting, plus other devices on the same circuit. Stay below 80% of breaker rating (e.g., ≤12 A on a 15-A circuit).

- Inspect for heat. After 30 minutes of operation, gently feel connectors and the first 12 inches of wire. Warmth is normal. Hot-to-touch? Unplug immediately—there’s excessive resistance or undersized wiring.

- Test shunts before replacing bulbs. With power OFF, set a multimeter to continuity mode. Touch probes to the bulb’s metal base contacts. A working shunt will beep. No beep? The shunt is dead—replace the entire bulb assembly.

FAQ: Clear Answers to Common Confusion

Can I cut and rewire a strand to make it longer?

No—unless it’s explicitly designed for field-cutting (e.g., some commercial 12V LED rope lights with IP67-rated connectors). Consumer strands use proprietary voltage distribution. Cutting interrupts the series-parallel balance, risks overvoltage on remaining sections, and voids UL certification. It also creates shock and fire hazards from exposed conductors.

Why do some LED strands flicker only when dimmed?

Flickering during dimming usually indicates incompatibility between the strand’s internal driver and the wall dimmer. Most plug-in LED strands require trailing-edge (ELV) dimmers—not standard leading-edge (TRIAC) types used for incandescents. Check the strand’s spec sheet for dimmer compatibility; better yet, use a dedicated lighting controller instead of a wall dimmer.

Are battery-powered lights safer because they’re “low voltage”?

Not necessarily. While 3–12 V DC eliminates shock risk, poor-quality lithium batteries can overheat, swell, or ignite—especially in enclosed spaces or direct sun. Look for UN38.3 certification and integrated thermal cutoffs. Also note: battery lights still use series-parallel subsections internally; their runtime drops sharply as cells deplete and voltage sags below the driver’s minimum operating threshold.

Conclusion: Respect the Design, Not Just the Decor

That little strand of lights on your porch or mantel is far more sophisticated than it appears. Its hybrid wiring isn’t a compromise—it’s a carefully balanced solution forged from decades of electrical safety standards, materials science, and real-world failure analysis. Knowing why series and parallel coexist empowers you to use lights as intended: safely, efficiently, and without frustration. It turns troubleshooting from random bulb-swapping into targeted diagnosis. It transforms “Why did half the strand go dark?” into “Which subsection lost voltage—and where’s the weak link?”

You don’t need an engineering degree to benefit from this knowledge. Just pause before plugging in that fourth strand. Read the label—not as fine print, but as a contract between the engineer who designed it and you, the person keeping your home bright and safe. Choose quality over quantity, verify compatibility before connecting, and treat your lights not as disposable decor—but as intelligently engineered systems worthy of thoughtful use.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?