Every holiday season, millions of households encounter the same quiet frustration: you’ve draped three strands across the porch railing, only to find the fourth one won’t light—or worse, trips the breaker. The instruction tag reads, “Do not connect more than three sets end-to-end.” You glance at your neighbor’s house glowing with a dozen uninterrupted strings and wonder: is that safe? Is it even legal? The answer isn’t about marketing or arbitrary rules—it’s rooted in fundamental electrical principles, decades of fire-safety regulation, and real-world physics. Understanding why these limits exist isn’t just about following directions—it’s about preventing overheating, avoiding circuit overload, and protecting your home and family.

The Core Issue: It’s All About Electrical Load, Not Just “More Lights”

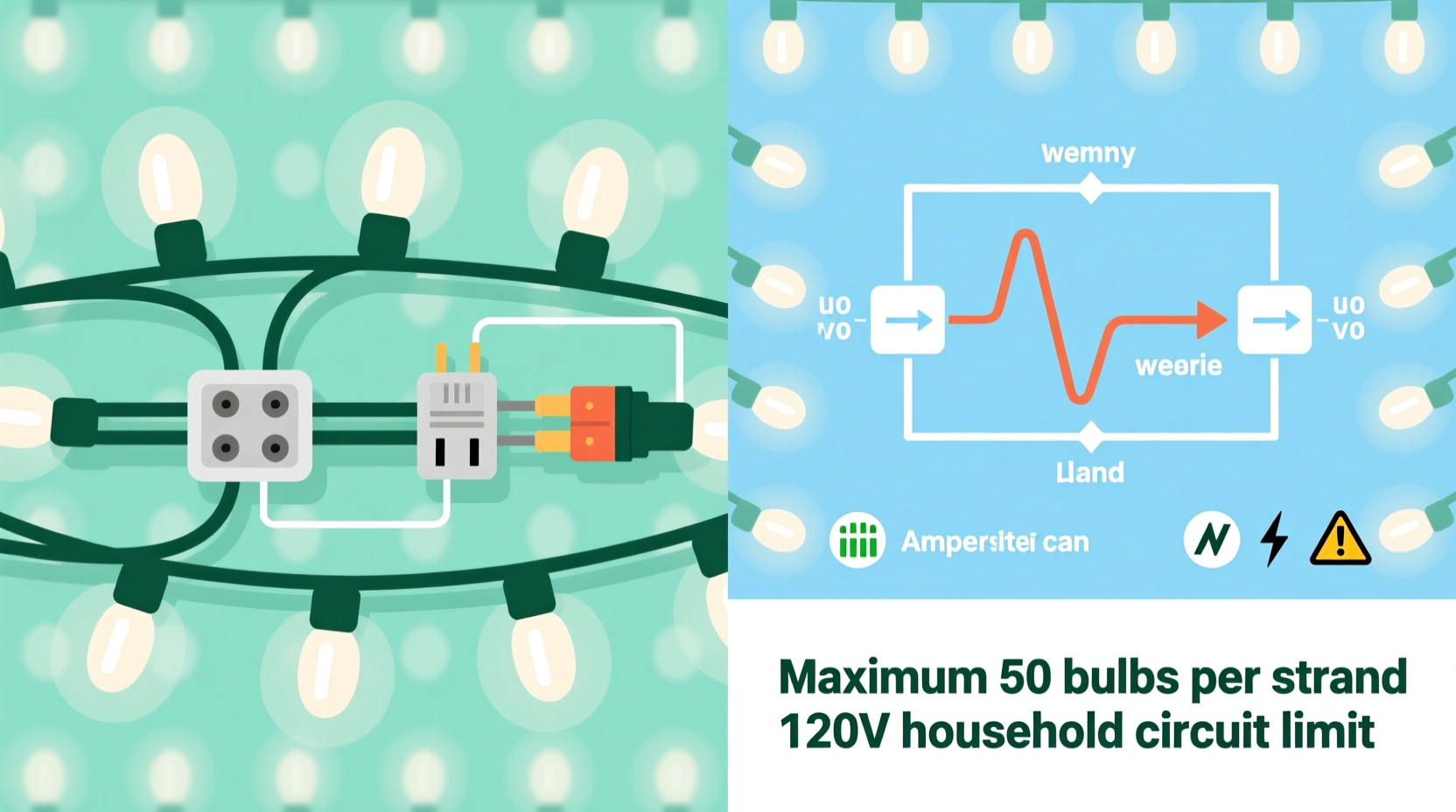

Christmas light strings—especially traditional incandescent and many LED varieties—are designed as *series-parallel hybrid circuits*. Each bulb operates at low voltage (typically 2.5V–3.5V for incandescents, slightly higher for LEDs), but the entire strand is engineered to run on standard 120V household current. To achieve this, manufacturers divide bulbs into groups wired in series (so voltage drops add up across each group), while those groups are wired in parallel to maintain consistent brightness and fault tolerance.

This architecture creates a predictable power draw per strand—usually listed on the UL label as watts (W) or amps (A). For example:

- A classic 100-bulb incandescent string draws ~40–60W (0.33–0.5A)

- A comparable LED string draws ~4–7W (0.03–0.06A)

- A heavy-duty commercial LED string may draw ~12–18W (0.1–0.15A)

But here’s what most people miss: the limit isn’t primarily about the *total wattage* your outlet can handle—it’s about the *voltage drop* and *wire gauge integrity* along the daisy-chained path. As current travels down a long chain of cords, resistance in the internal wiring causes voltage to decrease. By the time electricity reaches the 10th or 12th string, voltage may fall below 105V—enough to dim LEDs, flicker incandescents, or cause drivers to malfunction. More critically, undersized internal wiring heats up under sustained load, especially near connection points where poor contact increases resistance.

Three Engineering Constraints Behind the Limit

Manufacturers don’t set connection limits arbitrarily. They’re constrained by three interlocking physical realities:

- Wire Gauge and Thermal Capacity: Most consumer-grade light strings use 22–24 AWG (American Wire Gauge) internal wiring. While adequate for a single strand’s current, chaining too many multiplies cumulative amperage. At 0.5A per incandescent string, five strings draw 2.5A—well within a 15A circuit’s capacity—but that current flows through the *first string’s internal wires*, which were only rated for 0.5A continuous duty. Sustained overload causes insulation degradation and hot spots.

- Voltage Drop Across Length: Every foot of wire adds resistance. A typical 25-foot string has ~0.5Ω of resistance. With 0.5A flowing, that’s a 0.25V drop per string. Chain ten strings, and you lose 2.5V before the first bulb—even before accounting for connector resistance (which often adds 0.1–0.3Ω per plug). Dimming, uneven brightness, and premature LED failure follow.

- UL 588 Certification Requirements: Underwriters Laboratories’ Standard 588—the benchmark for seasonal decorative lighting—mandates rigorous testing for heat buildup, cord durability, and fault conditions. To earn the UL mark, manufacturers must prove their design remains safe *at the stated maximum connection count*. Exceeding it voids certification and liability coverage. That “3-string max” label isn’t a suggestion—it’s a tested thermal and electrical boundary.

Real-World Consequences: A Mini Case Study

In December 2021, a family in suburban Ohio decorated their two-story colonial with vintage-style incandescent lights. Eager to avoid visible extension cords, they daisy-chained eight 100-light strands—four on the front porch, four wrapping the columns—using only the built-in male/female plugs. The first three nights worked fine. On night four, the third string began emitting a faint acrid odor. By morning, the plastic housing near the female plug of the second string had warped and discolored. An electrician later found the internal wiring in that section had reached 142°F (61°C)—well above the 90°C rating for the PVC insulation. The copper conductors hadn’t melted, but the insulation was brittle and cracked. Had the setup run longer—or been near dry pine boughs—the risk of arc-fault ignition would have risen sharply.

This wasn’t negligence; it was a common misunderstanding. The family assumed “if it lights up, it’s safe.” But safety isn’t binary—it’s a gradient measured in degrees, resistance, and time. UL limits exist because they represent the threshold where risk transitions from negligible to unacceptable over extended operation (e.g., 8–12 hours nightly for six weeks).

How to Connect Lights Safely: A Step-by-Step Guide

Follow this sequence to maximize coverage while staying within code and manufacturer specifications:

- Identify Your Circuit’s Capacity: Locate your home’s breaker panel. Find the circuit powering your outdoor or living room outlets. Most residential circuits are 15A (1,800W) or 20A (2,400W). Deduct 20% for safety margin—so use no more than 1,440W on a 15A circuit.

- Calculate Total Load Per Outlet: Add up the wattage of *all* devices on that circuit—not just lights. A space heater (1,500W) and three light strings (150W) already exceed safe capacity.

- Use Manufacturer-Specified Limits as Absolute Maxima: If the label says “max 3 sets,” treat that as non-negotiable—even if your math says you’re under wattage limits. Those numbers account for worst-case scenarios: cold ambient temperatures (increasing resistance), dusty connectors, and aging insulation.

- Prefer Parallel Over Daisy-Chaining: Instead of plugging string B into string A, plug both into a heavy-duty, UL-listed power strip with individual switches and built-in surge protection. This keeps current paths short and reduces cumulative voltage drop.

- Inspect Every Connection: Before powering on, ensure plugs are fully seated, pins aren’t bent, and no cord is pinched or kinked. Warmth at a plug after 15 minutes of operation signals excessive resistance—unplug immediately.

LED vs. Incandescent: Why LED Limits Are Higher (But Still Real)

Many assume LED lights eliminate connection concerns. While LEDs draw far less power, their limits persist—and for different reasons:

| Factor | Incandescent Strings | LED Strings |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Wattage/Strand | 40–60W | 4–12W |

| Max Recommended Connections (Standard) | 3–5 strings | 25–50+ strings |

| Primary Limiting Factor | Heat buildup in wires & bulbs | Power supply (driver) overload & voltage drop |

| Critical Failure Mode | Insulation meltdown, fire | Driver shutdown, flickering, color shift |

| Why “50 strings” Isn’t Always Safe | N/A — physically impossible | Long chains overwhelm driver regulation; cheap drivers fail silently, causing uneven current distribution |

High-quality LED strings include constant-current drivers that regulate output—but only within their design envelope. Chain 40 strings of a budget LED set rated for 20 max, and the final strings may receive inconsistent voltage, accelerating diode degradation. Premium commercial LEDs (e.g., those used on municipal displays) often feature active voltage compensation and thicker 18 AWG wiring—allowing 100+ connections—but they cost 3–5× more and require professional installation.

“Connection limits aren’t about restricting creativity—they’re about preserving the integrity of the entire system. We test every configuration for 1,000 hours at 110°F ambient temperature. If voltage drop exceeds 5% or surface temperature rises above 75°C at any point, we reduce the certified max count—even if it means losing market share.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Senior Electrical Engineer, Feit Electric Lighting R&D

FAQ: Clearing Up Common Misconceptions

Can I bypass the limit by using an outdoor-rated extension cord?

No. Extension cords don’t reset the daisy-chain physics. Plugging a 50-foot 14 AWG cord between strings still forces current from strings 4–10 to flow back through the first string’s internal wiring and connectors. The cord itself may handle the load, but the weakest link—the original string’s 22 AWG wires and molded plugs—remains unchanged. UL prohibits modifying certified products, and doing so voids insurance coverage.

Why do some “professional” lights allow 100+ connections while my store-bought ones don’t?

Commercial-grade lights use heavier gauge wiring (16–18 AWG), industrial-grade connectors with gold-plated contacts, and integrated voltage-regulating nodes every 10–15 feet. They’re also tested to stricter standards (e.g., UL 2388 for permanent installations). Consumer lights prioritize cost, flexibility, and shelf appeal—not all-night reliability in freezing rain. Don’t assume “brighter” or “more expensive” means “higher connection tolerance”—always verify the UL label.

If my lights feel warm, is that normal?

Slightly warm connectors (up to 104°F / 40°C) are typical for incandescents and some LEDs during extended use. However, if the cord itself feels hot to the touch—especially near plugs—or if you detect a burning smell, unplug immediately. This indicates dangerous resistance buildup, often caused by corroded contacts, damaged insulation, or exceeding connection limits. Never cover warm cords with fabric, mulch, or insulation.

Conclusion: Respect the Physics, Celebrate the Light

Christmas light connection limits exist not to frustrate decorators, but to honor immutable laws of electricity and materials science. They reflect decades of incident analysis—from the 1970s holiday fire surge that prompted UL 588’s creation to modern thermal imaging studies showing how quickly marginal setups degrade. When you adhere to those limits, you’re not following a rule—you’re participating in a collective commitment to safety, reliability, and thoughtful design. You’re choosing longevity over spectacle, and care over convenience. And that makes your display more meaningful, not less.

So this season, plan your layout with intention: use multiple outlets, invest in UL-listed power strips with individual controls, and choose quality over quantity. Test each string individually before connecting. Replace frayed cords or discolored plugs without hesitation. Your lights will shine brighter—not just visually, but ethically and responsibly.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?