The bright red, fleshy appendages dangling from a turkey’s head and neck—commonly known as wattles—are among the most distinctive features of this bird. While they may appear ornamental or even comical to human observers, wattles serve several vital biological functions. Far from being mere decoration, these structures play key roles in communication, temperature regulation, and reproductive success. Understanding why turkeys have wattles reveals much about avian evolution, social behavior, and physiological adaptation.

Anatomy of the Wattle: What Exactly Is It?

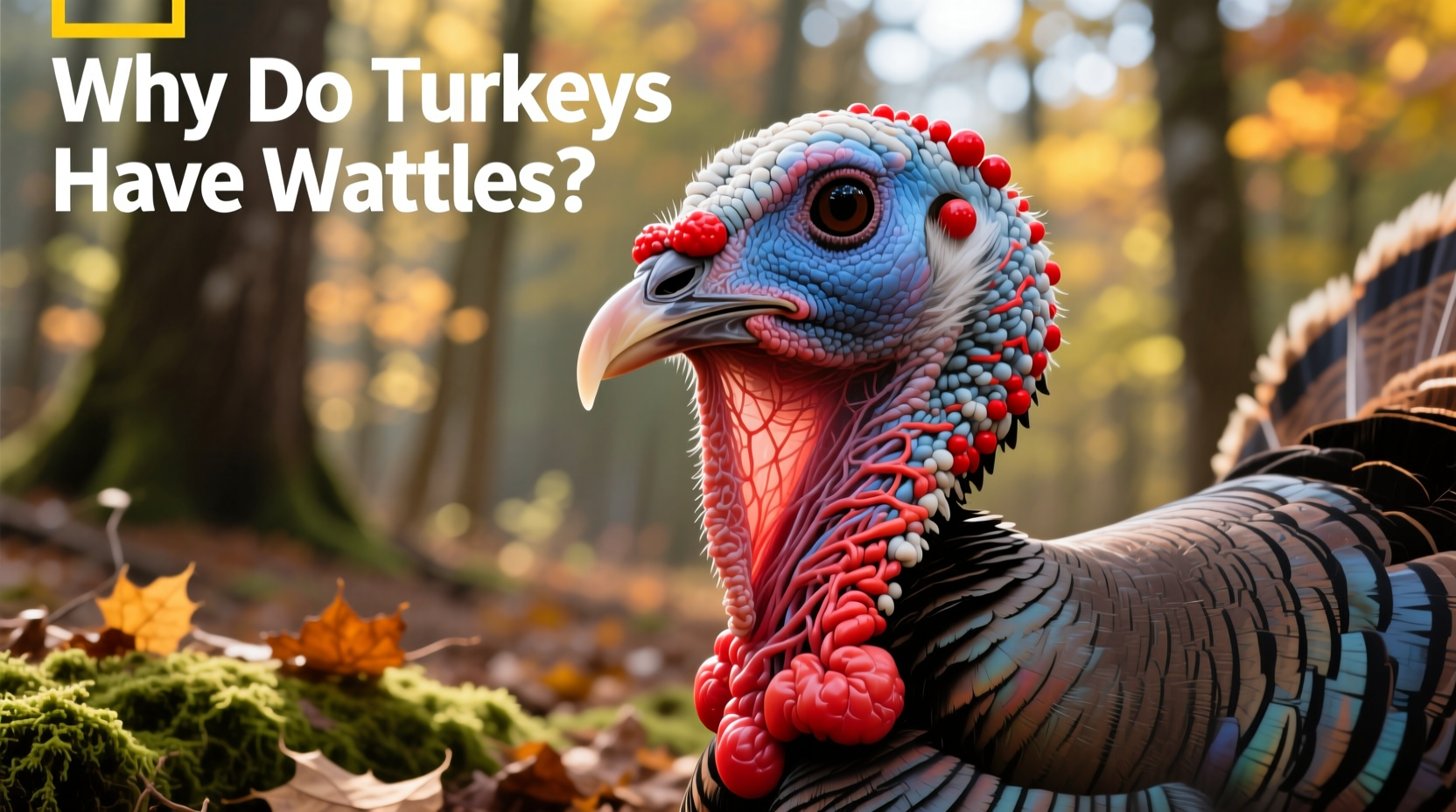

A wattle is a soft, fleshy lobe of skin that hangs from the lower jaw or throat area of certain birds, including turkeys, chickens, and some pheasants. In male turkeys (toms), wattles are especially prominent and become more pronounced during mating season. The wattle is highly vascularized, meaning it contains an extensive network of blood vessels just beneath the thin skin. This vascular structure is central to many of its functions.

Alongside the wattle, turkeys also possess other related anatomical features:

- Snood – a fleshy protrusion extending from the forehead over the beak.

- Caruncles – bumpy, fleshy growths on the head and neck.

- Beard – a tuft of specialized feathers on the chest (in males).

Together, these structures form part of the turkey’s display apparatus, used primarily for signaling within the species.

Thermoregulation: A Natural Cooling System

One of the most critical functions of the turkey wattle is thermoregulation. Turkeys, like all birds, lack sweat glands and must rely on alternative mechanisms to dissipate heat. The wattle acts as a thermal radiator. Because it is rich in blood vessels and exposed to air, it allows excess body heat to escape efficiently.

When a turkey is hot, blood flow to the wattle increases significantly. This process, known as vasodilation, brings warm blood close to the surface where it can cool before circulating back into the body. Conversely, in cold conditions, the blood vessels constrict (vasoconstriction), reducing heat loss.

This adaptation is particularly important for wild turkeys, which inhabit diverse climates across North America, from humid southeastern forests to arid southwestern regions. The wattle enhances their ability to maintain internal temperature stability without expending excessive energy.

Mating and Social Signaling: The Role of Wattles in Attraction

Perhaps the most visually striking role of the wattle is in courtship and dominance displays. During breeding season, male turkeys puff up their bodies, fan their tail feathers, and erect their snoods while their wattles and caruncles become intensely engorged with blood, turning a vivid red or even blue-purple hue.

Females (hens) use these visual cues to assess potential mates. Research has shown that hens prefer males with larger, brighter wattles. These traits signal good health, strong immune function, and genetic fitness. A vibrant wattle indicates that a male is not currently infected or stressed, making him a more desirable partner.

“Wattles and snoods act as honest signals of male quality. They’re difficult to fake because poor health directly affects blood flow and tissue condition.” — Dr. Richard Buchholz, Avian Behavioral Ecologist, University of Mississippi

In addition to attracting females, wattles also help establish social hierarchy among males. Dominant toms typically have more developed wattles, and subordinates often defer to them during confrontations. The dynamic color changes—rapid shifts from pale pink to deep red—can communicate aggression, submission, or arousal in real time.

Health Indicator: A Window into Internal Condition

The appearance of a turkey’s wattle provides valuable information about its physiological state. Healthy turkeys exhibit firm, brightly colored wattles with consistent texture. In contrast, signs of illness often manifest first in these sensitive tissues:

- Pale or bluish wattles may indicate poor circulation or respiratory distress.

- Swollen, crusty, or discolored wattles can signal bacterial or fungal infections such as fowl cholera or avian pox.

- Shrunken or flaccid wattles may point to dehydration or malnutrition.

For poultry farmers and wildlife biologists, monitoring wattle condition is a non-invasive way to assess flock health. In domestic settings, sudden changes in wattle color or size often prompt early intervention, preventing the spread of disease.

| Wattle Appearance | Possible Meaning | Action Recommended |

|---|---|---|

| Bright red, firm | Healthy, alert | Normal observation |

| Pale or yellowish | Anemia, liver issues | Veterinary checkup |

| Swollen, oozing | Infection (e.g., avian diphtheria) | Isolate and treat |

| Cyanotic (blue-tinged) | Respiratory distress | Immediate care needed |

Evolutionary Perspective: Why Did Wattles Develop?

The evolution of wattles in turkeys is best understood through the lens of sexual selection and environmental adaptation. While both male and female turkeys have wattles, they are significantly larger and more colorful in males—a classic example of sexual dimorphism driven by mate choice.

Charles Darwin first described sexual selection as a force distinct from natural selection, where traits evolve not because they improve survival, but because they increase mating success. In turkeys, wattles likely began as minor vascular structures aiding in heat exchange. Over time, as females began preferring males with more conspicuous wattles, those traits were amplified through generations.

Interestingly, studies suggest that wattle size and color are correlated with testosterone levels. Higher testosterone leads to greater development of secondary sexual characteristics, including wattles. However, elevated testosterone can also suppress immune function, creating a trade-off. Only males with robust genetics can afford to maintain large wattles without succumbing to disease—making the wattle an “honest signal” of fitness.

Mini Case Study: Wild Turkey Mating Grounds in Appalachia

In the spring woods of western Virginia, researchers observed a group of wild turkeys during peak breeding season. One dominant tom, identifiable by his long snood and deep crimson wattle, attracted the majority of hens in the area. Subordinate males, though physically capable, remained on the periphery, their wattles noticeably paler.

Over three weeks, the lead male mated with seven different hens. When he was temporarily displaced by a younger rival, his wattle rapidly paled—a visible sign of stress-induced vasoconstriction. Within days, he regained dominance, and his wattle returned to full coloration. Biologists noted that no hens approached the younger male during his brief ascendancy, suggesting that rapid physiological responses in wattles influence real-time social dynamics.

Practical Tips for Observing and Understanding Turkey Wattles

Whether you're a backyard poultry keeper, hunter, or nature enthusiast, paying attention to wattles can enhance your understanding of turkey behavior and health. Here’s how to make the most of this knowledge:

- Monitor wattle color daily in domestic flocks to catch illness early.

- Provide shade and fresh water to support thermoregulation in hot weather.

- Avoid overcrowding, which increases stress and dulls wattle vibrancy.

- Photograph wattles periodically to track long-term health trends.

- Respect personal space when observing wild turkeys; stress causes temporary wattle shrinkage, skewing observations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do female turkeys have wattles?

Yes, female turkeys (hens) have wattles, but they are much smaller and less colorful than those of males. Hens use them for thermoregulation and limited social signaling, though not for courtship displays.

Can a turkey survive without its wattle?

While a turkey can survive with a damaged or missing wattle, it may suffer impaired thermoregulation and reduced social status. In domestic settings, injuries should be treated promptly to prevent infection.

Why does a turkey’s wattle change color so quickly?

The rapid color change is due to shifts in blood flow controlled by the autonomic nervous system. Excitement, fear, mating displays, or temperature changes can alter blood vessel dilation within seconds.

Conclusion: More Than Meets the Eye

The turkey’s wattle is far more than a quirky facial feature—it is a multifunctional organ shaped by millions of years of evolution. From helping regulate body temperature to serving as a billboard of health and virility, the wattle plays a silent but essential role in the life of every turkey. By understanding its purpose, we gain deeper insight into avian biology, animal communication, and the subtle ways nature balances survival with reproduction.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?