Volcanoes have shaped the surface of our planet for billions of years. Their explosive eruptions can devastate communities, alter climates, and even influence the course of evolution. Yet beneath the spectacle lies a complex interplay of geological forces. Understanding why volcanoes erupt requires examining the inner workings of Earth—from the movement of tectonic plates to the behavior of molten rock deep beneath the crust. This article breaks down the science behind volcanic activity, explaining how pressure builds, what triggers an eruption, and why some volcanoes are more dangerous than others.

The Structure of a Volcano: What Lies Beneath

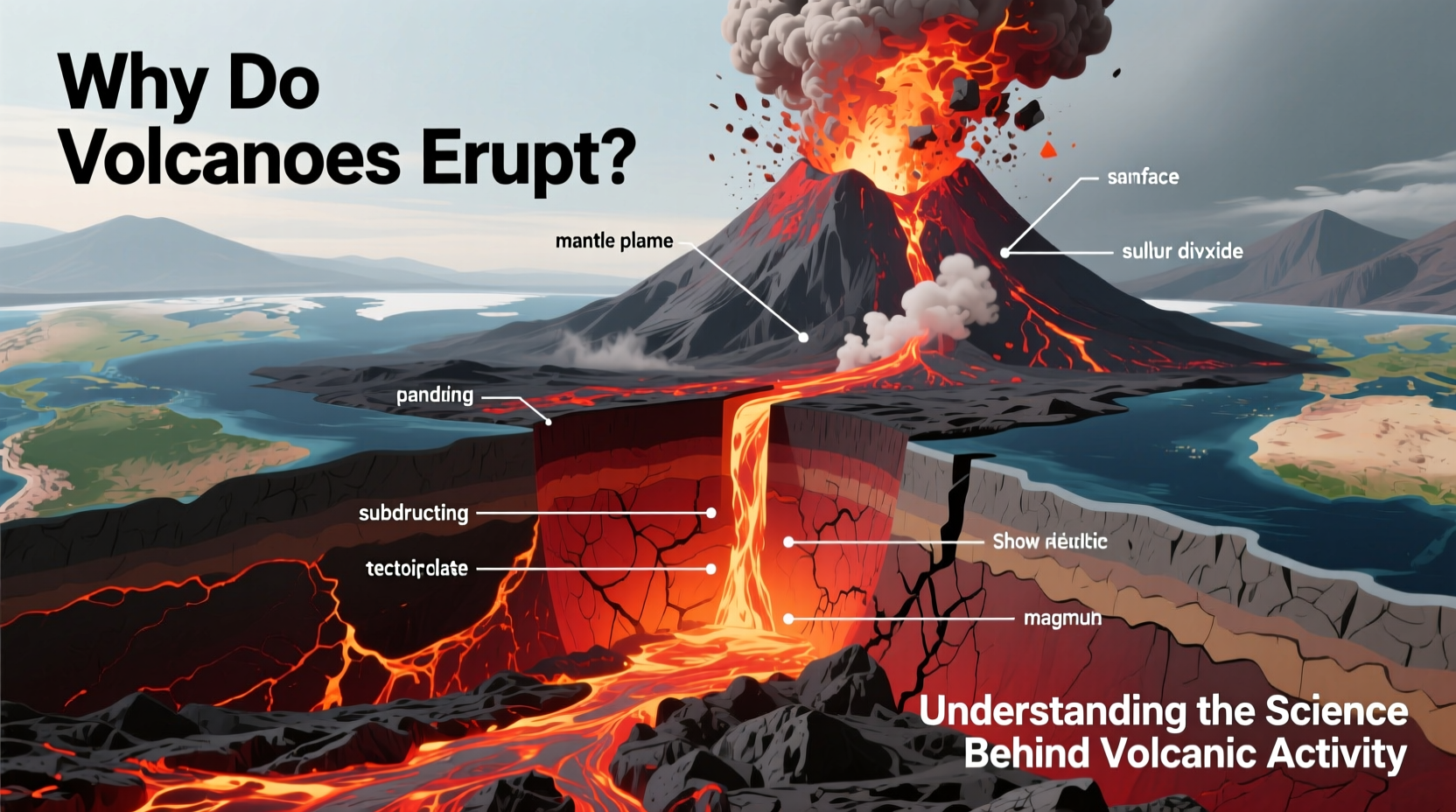

A volcano is not simply a mountain that occasionally spews lava. It is a conduit system connecting Earth's interior to its surface. At its core is the magma chamber—a reservoir of molten rock located several kilometers below ground. Magma rises through fractures in the crust due to buoyancy and pressure differences. As it ascends, it collects in secondary pockets before reaching the surface via a central vent or fissures.

The composition of the magma plays a crucial role in determining eruption style. Magma rich in silica (felsic) is thick and sticky, trapping gases and leading to explosive eruptions. In contrast, low-silica (mafic) magma flows more easily, allowing gases to escape gradually, resulting in effusive, lava-flowing eruptions.

Tectonic Forces: The Engine Behind Volcanism

Most volcanoes form at plate boundaries, where massive sections of Earth’s lithosphere interact. There are three primary settings where volcanic activity occurs:

- Divergent boundaries: Plates pull apart, creating gaps where magma rises to fill the space. This process forms mid-ocean ridges and rift valleys, such as Iceland’s volcanic zones.

- Convergent boundaries: One plate subducts beneath another, dragging water-rich minerals into the mantle. This lowers the melting point of rock, generating magma that fuels explosive arc volcanoes like Mount St. Helens.

- Hotspots: These occur away from plate edges, where plumes of hot material rise from deep within the mantle. The Hawaiian Islands are a classic example, formed as the Pacific Plate moved over a stationary hotspot.

“Volcanoes are Earth’s pressure valves. They release heat and material from the interior, helping regulate planetary dynamics.” — Dr. Susan Ellis, Geophysicist, GNS Science

What Triggers an Eruption?

An eruption does not happen spontaneously. It results from a critical buildup of pressure within the magma system. Several factors contribute to this tipping point:

- Magma accumulation: As new magma enters the chamber, pressure increases. If the overlying rock cannot withstand the stress, fractures form, allowing magma to rise.

- Gas expansion: Dissolved gases like water vapor, carbon dioxide, and sulfur dioxide come out of solution as pressure drops during ascent. This expansion can shatter surrounding rock and propel magma violently upward.

- External triggers: Earthquakes, landslides, or even heavy rainfall can destabilize a volcanic system, acting as a final catalyst for eruption.

The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens was triggered by a magnitude 5.1 earthquake that caused the north flank of the mountain to collapse. This sudden unloading released pressure on the magma chamber, leading to a lateral blast that flattened forests over 600 square kilometers.

Step-by-Step: The Eruption Process Timeline

Understanding the sequence of events leading to an eruption helps scientists predict and monitor volcanic hazards. Here’s a simplified timeline:

- Weeks to months before: Increased seismic activity (volcanic tremors), ground deformation detected by GPS, and gas emissions signal magma movement.

- Days before: Swarms of small earthquakes indicate fracturing rock as magma pushes upward.

- Hours before: Surface swelling, steam explosions, or changes in gas composition may occur.

- Eruption onset: Either a violent explosion (if gas pressure is high) or a steady lava flow (if gases escape easily).

- Post-eruption: Activity may continue with ash emissions, pyroclastic flows, or lava dome growth over days or weeks.

Types of Volcanic Eruptions and Their Characteristics

Not all eruptions are alike. Scientists classify them based on explosiveness, ejecta type, and duration. Below is a comparison of common eruption types:

| Eruption Type | Magma Composition | Explosiveness | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hawaiian | Basaltic (low silica) | Low | Kīlauea, Hawaii |

| Strombolian | Basaltic to andesitic | Moderate | Stromboli, Italy |

| Vulcanian | Andesitic to dacitic | High | Sakurajima, Japan |

| Plinian | Rhyolitic (high silica) | Very High | Mount Vesuvius, 79 AD |

| Phreatomagmatic | Any, with water interaction | Variable | Surtsey, Iceland |

Plinian eruptions, named after Pliny the Younger who described Vesuvius’ destruction of Pompeii, are among the most catastrophic. They produce towering eruption columns that inject ash into the stratosphere, affecting global climate. The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora led to the “Year Without a Summer” in 1816, causing crop failures and famine worldwide.

Monitoring and Predicting Volcanic Activity

While we cannot prevent eruptions, modern technology allows us to forecast them with increasing accuracy. Volcano observatories use networks of instruments to detect early warning signs:

- Seismometers: Track earthquake patterns linked to magma movement.

- GPS and tiltmeters: Measure ground deformation indicating inflation of the magma chamber.

- Gas sensors: Monitor changes in sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide levels.

- Satellite imagery: Detect thermal anomalies and large-scale surface changes.

Mini Case Study: The 2010 Eyjafjallajökull Eruption

In April 2010, the relatively small Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajökull erupted beneath a glacier. The interaction between magma and ice caused a phreatomagmatic explosion, fragmenting the lava into fine ash. Winds carried the ash cloud across Europe, grounding over 100,000 flights and disrupting air travel for nearly a week.

This event highlighted how even modest eruptions can have global consequences when atmospheric conditions align. It also underscored the importance of international coordination in volcanic risk management and aviation safety protocols.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can we predict exactly when a volcano will erupt?

No single method provides exact timing. However, by combining seismic data, gas measurements, and deformation monitoring, scientists can issue probabilistic forecasts and alert authorities days or weeks in advance.

Are all volcanoes dangerous?

No. Many volcanoes are dormant or extinct. Even active ones vary widely in hazard level. Shield volcanoes like those in Hawaii pose less immediate danger due to slow-moving lava flows, while stratovolcanoes like Fuji or Rainier threaten with pyroclastic surges, lahars, and ashfall.

Do volcanoes only occur on land?

No. Most volcanoes are submarine, found along mid-ocean ridges. These undersea eruptions go largely unnoticed but account for the majority of Earth’s volcanic activity.

Conclusion: Respecting Nature’s Power

Volcanoes are not just destructive forces—they are vital components of Earth’s geologic engine. They recycle crustal material, create new land, and contribute to the atmosphere and oceans over millions of years. By understanding the science behind eruptions, we gain not only predictive power but also a deeper appreciation for the dynamic planet we inhabit.

Whether you live near an active zone or simply marvel at nature’s might, staying informed about volcanic processes empowers better preparedness and respect for Earth’s inner energy. As monitoring improves and global cooperation strengthens, our ability to coexist with these natural wonders grows stronger.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?