Dreams have fascinated humanity for centuries. From ancient civilizations interpreting them as divine messages to modern neuroscientists analyzing brain waves during sleep, the question of why we dream remains both mysterious and deeply compelling. While no single theory explains every aspect of dreaming, decades of research in neuroscience, psychology, and cognitive science have uncovered key insights into the mechanisms and potential functions of dreams. This article explores the leading scientific theories, examines what happens in the brain during dreaming, and offers practical understanding of how dreams may influence waking life.

The Neuroscience of Dreaming: What Happens in the Brain?

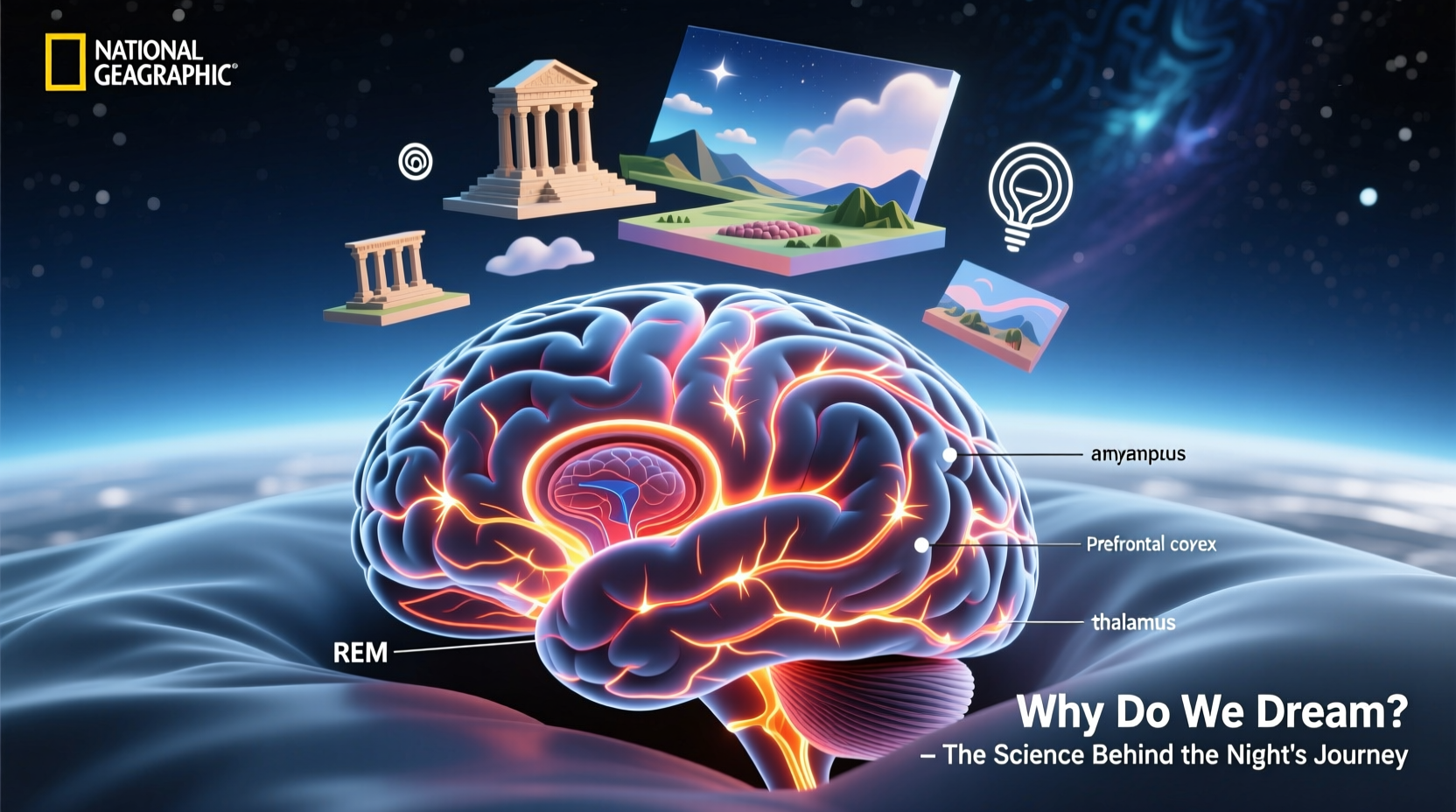

Dreaming primarily occurs during the Rapid Eye Movement (REM) stage of sleep, a phase characterized by heightened brain activity, rapid eye movements, and muscle atonia—where the body becomes temporarily paralyzed to prevent acting out dreams. During REM sleep, the brain's electrical activity closely resembles that of wakefulness, particularly in regions associated with emotion, memory, and visual processing.

The limbic system, especially the amygdala and hippocampus, becomes highly active during REM. The amygdala governs emotional responses, which may explain why dreams often carry intense feelings—fear, joy, anxiety. Meanwhile, the hippocampus plays a crucial role in consolidating memories, suggesting a link between dreaming and memory integration.

In contrast, areas responsible for logical reasoning and self-awareness—such as the prefrontal cortex—are significantly less active. This diminished executive function helps explain the bizarre, illogical nature of many dreams, where time, space, and identity shift unpredictably.

Major Scientific Theories Behind Why We Dream

Scientists have proposed several compelling theories to explain the purpose of dreams. While none are universally accepted, each contributes valuable insight into the complex phenomenon of dreaming.

1. Memory Consolidation Theory

This theory suggests that dreaming plays a critical role in processing and organizing daily experiences. During sleep, particularly in REM and slow-wave sleep stages, the brain replays and strengthens neural connections formed during waking hours. Dreams may be a byproduct of this internal \"rehearsal,\" helping integrate new information with existing knowledge.

Studies show that people who get adequate REM sleep perform better on memory tasks, especially those involving procedural or emotional memory. For example, after learning a new skill like playing piano, individuals who dream about the task often demonstrate improved performance the next day.

2. Threat Simulation Theory

Proposed by Finnish psychologist Antti Revonsuo, this evolutionary theory posits that dreams evolved as a survival mechanism. By simulating threatening scenarios—being chased, falling, or facing danger—the brain practices responses in a safe environment. This rehearsal could enhance real-world threat detection and reaction speed.

Research supports this idea: children and adults across cultures frequently report dreams involving pursuit, attack, or escape. Even in modern, relatively safe environments, these themes persist, suggesting deep-rooted biological programming.

“Dreams may be the mind’s way of running emergency drills—preparing us for dangers we hope never to face.” — Dr. Rosalind Cartwright, Sleep Researcher and Pioneer in Dream Science

3. Emotional Regulation Hypothesis

Dreams may help regulate emotions by allowing the brain to process unresolved feelings in a detached setting. During REM sleep, stress-related neurotransmitters like norepinephrine are suppressed, while emotional circuits remain active. This creates a unique state where emotional memories can be revisited without the intensity of real-time distress.

A 2011 study from Harvard Medical School found that participants who dreamed about emotionally charged events showed reduced reactivity when later exposed to related stimuli. This suggests dreams may act as a form of overnight therapy, softening emotional edges and promoting psychological resilience.

4. Activation-Synthesis Model

Introduced by Harvard researchers J. Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley in the 1970s, this neurobiological model argues that dreams are not inherently meaningful. Instead, they result from random neural firing in the brainstem during REM sleep. The cerebral cortex then attempts to make sense of this chaotic activity by weaving it into a narrative—hence the often surreal storyline of dreams.

While this theory downplays symbolic interpretation, it laid the foundation for understanding dreams as a product of brain physiology rather than supernatural messages.

5. Cognitive Development and Problem-Solving

Some researchers believe dreams contribute to creativity and problem-solving. In a dream state, the brain makes novel associations unbound by logic or constraints. This can lead to unexpected insights—famously illustrated by chemist August Kekulé, who claimed he discovered the ring structure of benzene after dreaming of snakes biting their own tails.

Modern studies support this: individuals awakened during REM sleep perform better on tasks requiring flexible thinking and pattern recognition compared to those deprived of REM.

Common Dream Themes and Their Possible Meanings

Certain dream motifs appear across cultures and age groups. While interpretations vary, scientific analysis links them to universal human concerns:

| Dream Theme | Possible Psychological Basis | Associated Emotion |

|---|---|---|

| Falling | Loss of control, insecurity | Anxiety |

| Being Chased | Avoidance of conflict or responsibility | Fear |

| Teeth Falling Out | Concerns about appearance or communication | Shame, vulnerability |

| Flying | Desire for freedom or escape | Joy, empowerment |

| Being Unprepared for a Test | Fear of judgment or failure | Stress |

These patterns suggest that dreams reflect underlying emotional states and unresolved cognitive challenges, even if expressed symbolically.

Mini Case Study: How Dream Journaling Improved Emotional Awareness

Sophie, a 32-year-old graphic designer, began experiencing recurring nightmares about being trapped in collapsing buildings. After weeks of disrupted sleep, she started keeping a dream journal as part of a mindfulness program. Over time, she noticed a connection between these dreams and her growing anxiety about job security during company restructuring.

By identifying the emotional trigger, Sophie was able to address her fears through therapy and open conversations with her manager. Within two months, the nightmares subsided, replaced by more neutral or positive dreams. Her case illustrates how examining dreams can uncover subconscious stressors and support emotional well-being.

Step-by-Step Guide to Understanding Your Dreams

While dreams cannot always be controlled, you can develop greater awareness and insight through consistent practice:

- Set Intentions Before Sleep: Tell yourself, “I will remember my dreams tonight,” to prime recall.

- Keep a Journal Nearby: Place a notebook and pen (or voice recorder) within reach of your bed.

- Write Immediately Upon Waking: Capture fragments, emotions, colors, or sounds—even if the full narrative isn’t clear.

- Note Recurring Elements: Track characters, locations, or actions that repeat over time.

- Reflect on Waking Life: Consider current stressors, goals, or emotional conflicts that might be mirrored in dreams.

- Look for Patterns, Not Literal Meanings: Focus on emotional tone and symbolism rather than expecting direct predictions.

FAQ

Do blind people dream?

Yes, but the content depends on when they lost their vision. Those born blind typically experience dreams rich in sound, touch, smell, and emotion, but not visual imagery. People who became blind later in life may still have visual components in their dreams for years afterward.

Can you control your dreams?

Some people can achieve lucid dreaming—becoming aware they’re dreaming and influencing the dream’s course. Techniques like reality testing, meditation, and mnemonic induction can increase the likelihood of lucidity, though success varies.

Is it bad if I don’t remember my dreams?

No. Dream amnesia is normal. Most dreams are forgotten within minutes of waking due to low levels of acetylcholine and norepinephrine upon awakening. Improving sleep quality and using a journal can enhance recall, but forgetting dreams doesn’t indicate any health issue.

Conclusion: Embracing the Mystery of Dreams

Dreams remain one of the most intimate and enigmatic features of human consciousness. Whether serving as emotional regulators, memory organizers, or evolutionary simulations, they offer a window into the subconscious mind. While science continues to unravel their mechanisms, the personal value of dreams lies in their ability to reveal hidden fears, inspire creativity, and deepen self-understanding.

You don’t need to be a neuroscientist to benefit from your dreams. Simple practices like journaling, reflection, and quality sleep hygiene can transform nighttime visions into tools for growth. As research advances, so too does our appreciation for the silent, nightly journeys that shape who we are.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?