Sweating is one of the most natural and essential bodily responses during physical activity. Whether you're jogging in summer heat or pushing through a high-intensity interval session indoors, perspiration is almost inevitable. Yet, many people view sweating as merely an inconvenience—something to wipe away or mask with deodorant. In reality, sweat plays a vital role in maintaining physiological balance and protecting your body from overheating. Understanding why we sweat during exercise offers insight into our body’s remarkable ability to adapt, perform, and recover.

The Science Behind Sweating

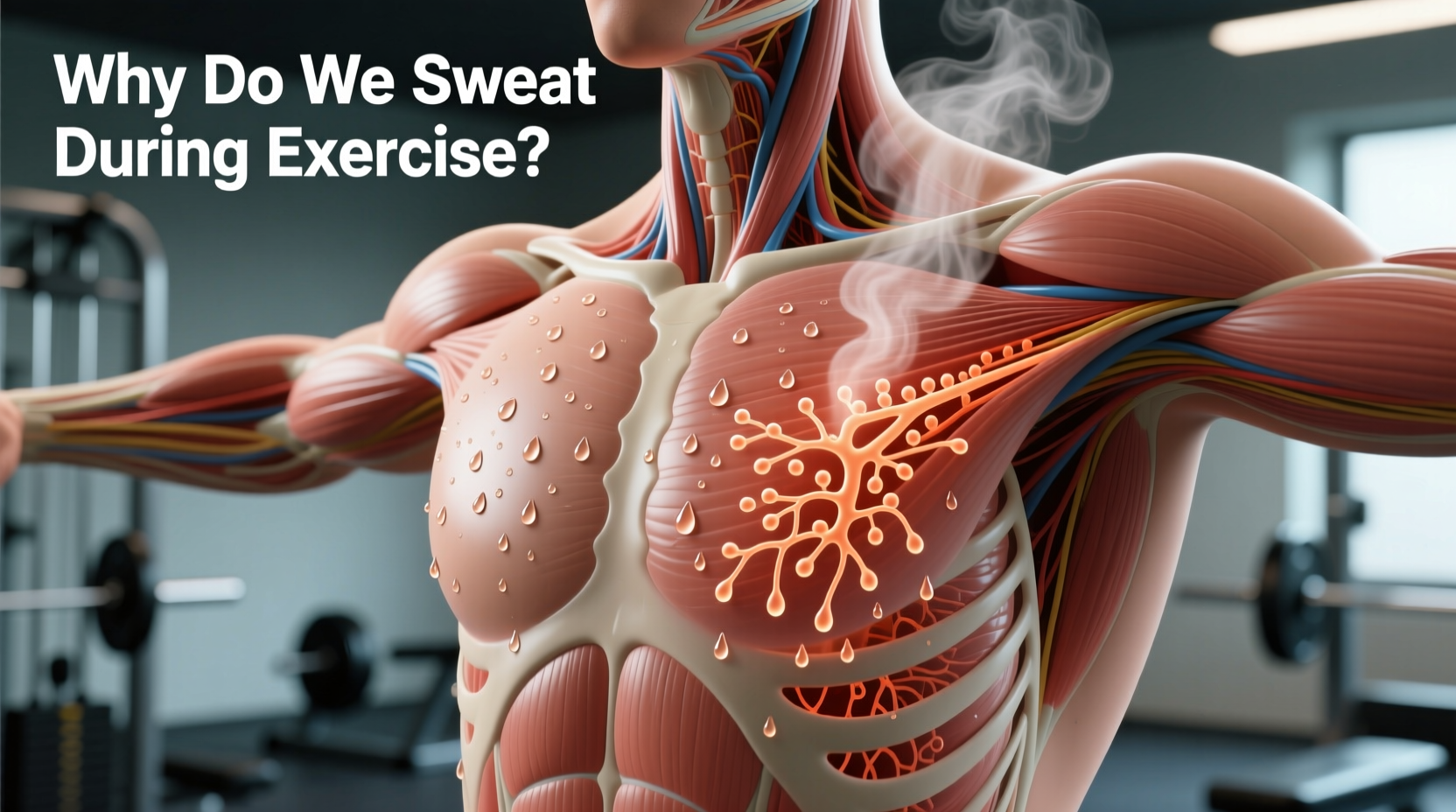

At its core, sweating is your body’s primary method of thermoregulation—maintaining a stable internal temperature despite external conditions or metabolic changes. When you exercise, your muscles generate heat as they contract. This increases your core body temperature. To prevent dangerous overheating, your central nervous system signals the eccrine sweat glands, distributed across your skin, to produce sweat.

Sweat is primarily composed of water, with small amounts of electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and chloride. As this moisture evaporates from the skin's surface, it draws heat away from the body, effectively cooling you down. The process is remarkably efficient: just one liter of sweat evaporation can dissipate approximately 580 kilocalories of heat.

“Sweating isn’t a sign of weakness—it’s a sign your body is working exactly as it should.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Exercise Physiologist at the National Institute of Human Performance

Types of Sweat Glands and Their Roles

Not all sweat is created equal. Your body houses two main types of sweat glands, each serving different purposes:

- Eccrine glands: Found all over the body, especially on palms, soles, and forehead. These are activated by heat and physical exertion, releasing odorless, watery sweat to cool the skin.

- Apocrine glands: Located primarily in the armpits and groin. These become active during puberty and respond more to emotional stress than heat. They secrete a thicker fluid that, when broken down by bacteria, causes body odor.

During exercise, eccrine glands dominate the response. The volume and rate of sweat production depend on factors such as fitness level, environment, clothing, and hydration status.

Factors That Influence Sweat Rate

No two individuals sweat the same way. Several variables determine how much—and how quickly—you perspire during physical activity.

| Factor | Impact on Sweating |

|---|---|

| Fitness Level | Highly fit individuals often start sweating earlier and more efficiently, allowing better heat dissipation. |

| Environmental Conditions | Heat and humidity increase sweat production; however, high humidity reduces evaporation, making cooling less effective. |

| Body Size and Composition | Larger bodies generate more heat and typically sweat more. Higher muscle mass also increases metabolic heat output. |

| Hydration Status | Dehydration reduces sweat rate and impairs thermoregulation, increasing risk of heat illness. |

| Clothing Material | Synthetic, non-breathable fabrics trap heat and reduce evaporation, leading to discomfort and overheating. |

What Your Sweat Says About Your Fitness

Your sweating pattern can serve as an informal barometer of physical conditioning. Trained athletes tend to sweat sooner into a workout and distribute sweat more evenly across their skin. This adaptation develops over time as the body becomes more efficient at detecting and responding to rising core temperatures.

In contrast, untrained individuals may experience delayed onset of sweating, causing their body temperature to rise more rapidly. This lag increases the risk of heat exhaustion, particularly in warm environments.

Additionally, regular exercisers often have lower sodium concentration in their sweat—a sign of improved electrolyte conservation. Their bodies learn to retain essential minerals while still maintaining cooling efficiency.

Mini Case Study: Adaptation in Action

Consider James, a 35-year-old office worker who began training for his first 10K race. During his initial runs in May, he would feel overheated within minutes, drenched in sweat, and frequently had to stop. By July, after consistent outdoor running three times a week, he noticed he started sweating sooner but felt cooler overall. His heart rate was lower at the same pace, and he completed longer distances without fatigue.

This shift illustrates heat acclimatization—a physiological adaptation where the body improves sweat response, blood flow to the skin, and plasma volume over 7–14 days of repeated heat exposure. James didn’t just get fitter—he became more thermally resilient.

Common Misconceptions About Sweating

Despite its biological importance, several myths persist around perspiration:

- Myth: Sweating burns fat. Reality: While exercise that causes sweating burns calories, sweat itself is mostly water loss, not fat loss. Rapid weight drop post-workout is temporary water weight.

- Myth: More sweat means a better workout. Reality: Workout quality depends on effort, intensity, and consistency—not sweat volume. A yoga session may produce less sweat than sprinting but still offer significant benefits.

- Myth: Sweating detoxifies the body. Reality: The liver and kidneys handle detoxification. Sweat contains trace amounts of urea and heavy metals, but it’s not a primary elimination pathway.

Step-by-Step Guide to Managing Sweat During Exercise

To make the most of your body’s natural cooling system while staying comfortable and safe, follow this practical sequence:

- Hydrate before you move: Drink 16–20 oz of water 1–2 hours before exercising, especially in warm conditions.

- Wear moisture-wicking clothing: Choose technical fabrics that pull sweat away from the skin and promote evaporation.

- Acclimatize gradually: If exercising in heat, begin with shorter sessions and progressively increase duration over 1–2 weeks.

- Monitor your sweat rate: Weigh yourself before and after a one-hour workout (without drinking). For every pound lost, you produced about 16 oz of sweat—use this to guide rehydration.

- Replenish electrolytes when needed: For workouts longer than 60–90 minutes, consider a drink with sodium and potassium to replace lost minerals.

- Cool strategically: Use damp towels, shaded breaks, or cooling vests during prolonged activity in hot environments.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it bad if I don’t sweat much during exercise?

Not necessarily. Low sweat output could be due to cool conditions, low intensity, or individual variation. However, if you consistently fail to sweat in hot environments or during intense effort, consult a healthcare provider—this could indicate anhidrosis, a condition impairing thermoregulation.

Can certain medications affect sweating?

Yes. Antihistamines, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and some blood pressure medications can reduce sweat production. Always monitor your body’s response to exercise when starting new medication.

Does sweating more mean I’m out of shape?

No. Sweating heavily can actually indicate your body is actively trying to cool itself. Over time, with improved fitness, your sweat response becomes more efficient—not necessarily less profuse.

Final Thoughts: Respecting the Role of Sweat

Sweat is far more than a bodily inconvenience—it’s a sophisticated, life-preserving mechanism honed by evolution. By understanding why we sweat during exercise, we gain deeper appreciation for the intricate systems that allow us to push our limits safely. Whether you're a weekend warrior or a seasoned athlete, listening to your body’s signals—including how, when, and how much you sweat—can improve performance, prevent injury, and support long-term health.

Instead of seeing sweat as something to avoid, embrace it as evidence of effort, adaptation, and resilience. The next time you finish a workout glistening with perspiration, remember: your body isn’t failing—it’s succeeding.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?