Yawning is one of the most universal yet mysterious behaviors humans—and many animals—perform daily. It happens when we're tired, bored, or even just seeing someone else yawn. Despite its frequency, the science behind yawning remains surprisingly complex. Why do we do it? Is it really contagious? And what does this tell us about our brains and social connections?

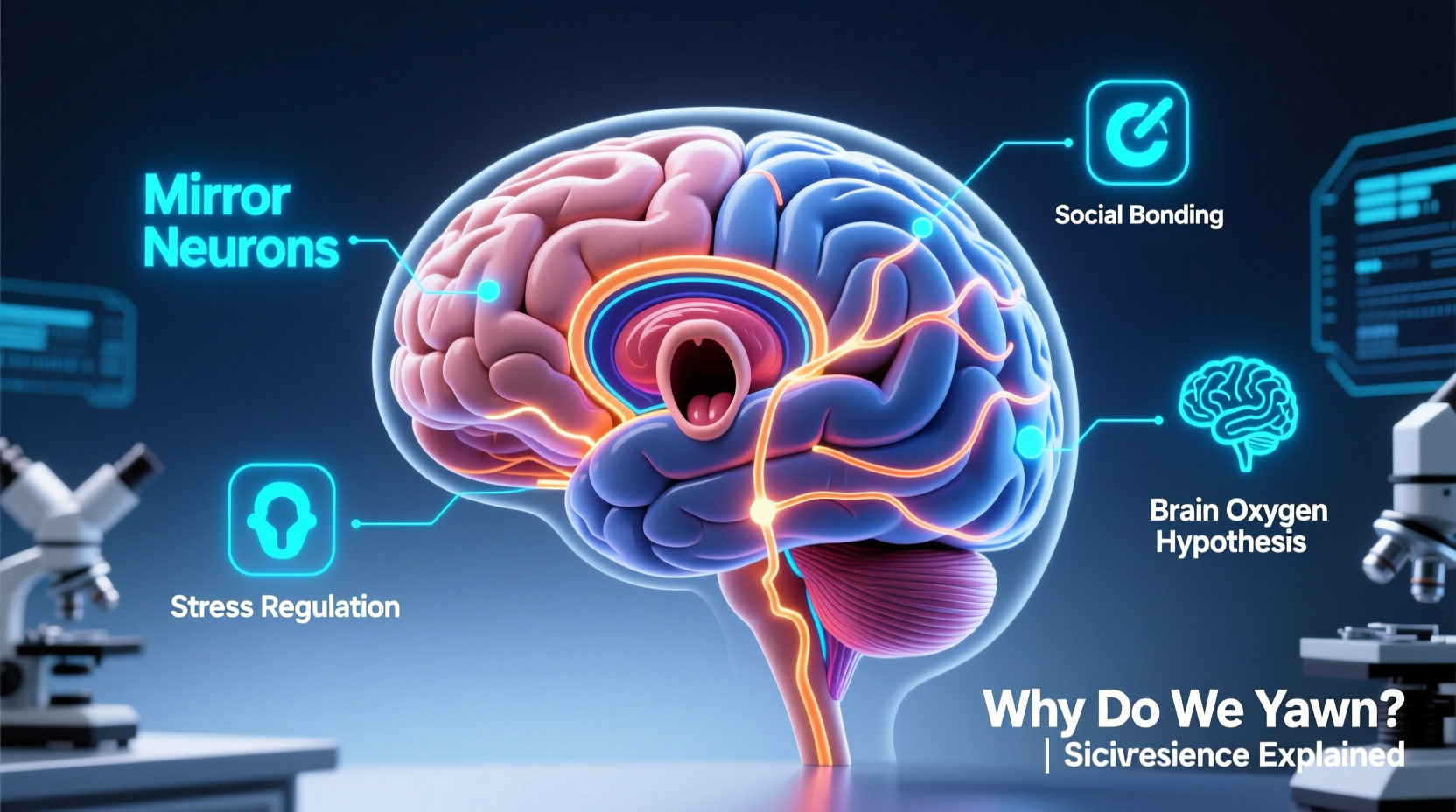

Neuroscience has made significant strides in unraveling the mechanisms behind yawning, linking it not only to physiological regulation but also to empathy, social bonding, and even neurological health. This article breaks down the latest research on yawning, exploring its biological purpose, the phenomenon of contagious yawning, and what it reveals about human cognition.

The Physiology of Yawning: More Than Just a Deep Breath

At its core, a yawn is an involuntary reflex involving a slow opening of the mouth, deep inhalation, brief pause, and then exhalation. It typically lasts around 5–10 seconds and engages muscles in the face, neck, and diaphragm. While often associated with fatigue or boredom, yawning occurs across all ages—even in fetuses by the ninth week of gestation—suggesting a deeper biological function.

One leading theory is that yawning helps regulate brain temperature. Research by Gallup and Gallup (2007) suggests that yawning acts as a natural \"brain cooler.\" When brain temperature rises slightly—due to sleepiness, stress, or prolonged concentration—yawning increases blood flow and brings cooler air into the nasal and oral cavities, effectively dissipating heat from the brain.

“Yawning may serve as a thermoregulatory mechanism for the brain, helping maintain optimal neural performance.” — Andrew C. Gallup, Evolutionary Psychologist

This theory is supported by studies showing that people yawn more frequently in warmer environments and less when their heads are cooled. For example, participants wearing cold packs on their foreheads yawned significantly less than those without cooling.

Another physiological explanation ties yawning to arousal regulation. Sudden shifts in alertness—like waking up or transitioning from work to rest—often trigger yawns. The act stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, increasing heart rate and oxygen intake, which may help prime the body for changes in activity level.

Contagious Yawning: A Mirror Neuron Mystery

If you’ve ever yawned after seeing someone else do it—or even reading about yawning—you’re not alone. Contagious yawning affects approximately 40–60% of adults and appears to be linked to social and cognitive processes rather than mere mimicry.

What makes this phenomenon especially fascinating is that it doesn’t occur uniformly across species or developmental stages. Humans don’t exhibit contagious yawning until around age four or five, coinciding with the development of empathy and theory of mind—the ability to understand others’ mental states.

Neuroimaging studies have shown that observing someone yawn activates regions of the brain associated with imitation and social cognition, particularly the mirror neuron system. These neurons fire both when we perform an action and when we see someone else perform it, forming a neural bridge between self and other.

Interestingly, individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), who often experience challenges in social perception, show reduced susceptibility to contagious yawning. This correlation strengthens the idea that contagious yawning is rooted in empathetic processing.

Who Yawns Back? Social and Emotional Triggers

Not everyone is equally susceptible to contagious yawning, and intriguing patterns emerge based on relationships and emotional bonds. Studies show that people are more likely to “catch” yawns from friends and family than from strangers. In one experiment, participants were nearly twice as likely to yawn after watching a loved one compared to an unfamiliar person.

This selectivity suggests that contagious yawning isn’t just a passive reflex—it’s modulated by emotional closeness. The stronger the bond, the higher the likelihood of synchronization through yawning. This aligns with findings in primates: chimpanzees, for instance, yawn contagiously more often with group members than outsiders.

Gender also plays a subtle role. Some research indicates that women may be slightly more responsive to contagious yawning than men, possibly due to higher average levels of empathy and social attunement. However, results vary across studies, indicating that individual differences outweigh broad demographic trends.

Empathy Levels and Yawning Susceptibility

| Group | Average Contagious Yawning Rate | Associated Traits |

|---|---|---|

| Children under 4 | Low (~15%) | Limited theory of mind development |

| Neurotypical Adults | Moderate-High (40–60%) | Strong empathy and social awareness |

| Autism Spectrum (ASD) | Reduced (~20–30%) | Challenges in social cognition |

| Closer Social Bonds | Up to 50% higher | Emotional familiarity enhances response |

| Psychopathy Traits | Lower incidence | Reduced empathetic engagement |

Neurological Insights: What Yawning Reveals About Brain Health

Beyond its social dimensions, yawning can serve as a window into neurological function. Excessive yawning—defined as more than once per minute over sustained periods—can signal underlying medical conditions such as migraines, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, or brainstem lesions.

In clinical settings, sudden onset of frequent yawning has been documented prior to seizures or stroke events. This is thought to stem from disruptions in the brainstem’s reticular activating system, which regulates arousal and autonomic functions—including yawning.

Dopamine also plays a key role. Experimental drugs that stimulate dopamine receptors (like apomorphine) induce yawning in animal models and humans. Conversely, dopamine antagonists used in antipsychotic medications can reduce yawning frequency. This pharmacological link underscores the neurotransmitter’s involvement in initiating the yawn reflex.

Moreover, yawning has been observed during withdrawal from opioids and SSRIs, suggesting it may reflect imbalances in serotonin and dopamine pathways. While occasional yawning is normal, persistent or unexplained episodes warrant medical evaluation, especially if accompanied by dizziness, headache, or focal weakness.

Mini Case Study: Yawning as an Early Warning Sign

Mark, a 52-year-old teacher, began experiencing episodes of excessive yawning—up to 20 times per hour—over several days. Initially dismissing it as fatigue, he later noticed mild imbalance and blurred vision. After visiting a neurologist, an MRI revealed a small lesion in his brainstem. Prompt treatment prevented further complications. His case highlights how a seemingly benign behavior like yawning can be an early red flag for serious neurological issues.

Debunking Common Myths About Yawning

Despite growing scientific understanding, myths about yawning persist. Let’s clarify some of the most widespread misconceptions:

- Myth: Yawning means you’re not getting enough oxygen.

Reality: Controlled studies show no correlation between blood oxygen levels and yawning frequency. Hyperventilation doesn’t stop yawning, and low-oxygen environments don’t consistently increase it. - Myth: Only humans and pets yawn contagiously.

Reality: Chimpanzees, dogs, wolves, and even budgerigars exhibit contagious yawning, especially in socially bonded pairs. - Myth: Holding back a yawn is harmless.

Reality: Suppressing a yawn may interfere with its proposed regulatory functions, potentially reducing alertness or impairing thermal balance in the brain.

Practical Tips for Managing Yawning in Daily Life

While yawning is largely involuntary, certain strategies can help manage its frequency and social impact, especially in professional or academic settings.

- Stay hydrated: Dehydration can increase fatigue and trigger yawning. Aim for consistent fluid intake throughout the day.

- Optimize sleep hygiene: Chronic tiredness leads to more frequent yawning. Maintain a regular sleep schedule and limit screen time before bed.

- Engage your mind: Boredom lowers arousal, prompting yawning. Introduce brief mental challenges—like counting backward or solving puzzles—to stay alert.

- Avoid eye contact during group fatigue: In meetings where others are yawning, breaking visual focus can reduce the chance of catching the yawn.

- Monitor medication side effects: If you notice increased yawning after starting a new drug, discuss it with your doctor—especially if it’s disruptive.

Checklist: When to Seek Medical Advice for Frequent Yawning

- Yawning more than once per minute for extended periods

- Sudden increase in yawning without obvious cause (e.g., sleep deprivation)

- Yawning accompanied by dizziness, headaches, or muscle weakness

- Yawning episodes preceding confusion or loss of consciousness

- History of neurological conditions like MS or epilepsy

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do I yawn when I’m not tired?

Yawning isn’t solely tied to sleepiness. It can occur during transitions in alertness, such as when starting a new task or shifting focus. It may also respond to rising brain temperature, stress, or boredom—all of which prompt the body to reset arousal levels.

Can animals catch yawns from humans?

Yes. Dogs, in particular, have demonstrated contagious yawning in response to their owners. Studies show they’re more likely to yawn after seeing a familiar human yawn, suggesting cross-species empathetic responses. Wolves and primates also show similar social contagion.

Is there a way to stop a yawn once it starts?

Once the yawn reflex begins, it’s difficult to stop. However, pressing the roof of your mouth with your tongue or taking a few quick sips of water may interrupt the sequence. Prevention—through staying cool, alert, and hydrated—is more effective than suppression.

Conclusion: The Hidden Intelligence Behind a Simple Yawn

What appears to be a simple, automatic act is actually a sophisticated interplay of biology, psychology, and social connection. From regulating brain temperature to reflecting empathetic capacity, yawning offers profound insights into how our bodies and minds function. Its contagious nature reminds us that human behavior is deeply intertwined with social context—our brains are wired to resonate with others, even in the smallest gestures.

Understanding the neuroscience behind yawning empowers us to recognize its signals—whether it’s time to rest, cool down, or pay attention to potential health concerns. It also deepens appreciation for the subtle ways we connect with one another, often without words.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?