Yawning is one of the most common yet mysterious behaviors humans—and many animals—exhibit. It happens when we're tired, bored, or even just seeing someone else yawn. Despite its frequency, the exact reasons for yawning remain a topic of scientific debate. What triggers it? Why does it feel so involuntary? And perhaps most curiously, why is yawning contagious? The answers lie in a complex interplay of neurology, physiology, and social psychology.

From newborns to primates, yawning spans species and developmental stages, suggesting deep evolutionary roots. Yet unlike reflexes such as blinking or sneezing, yawning carries layers of mystery, especially regarding its social transmission. This article explores the biological mechanisms behind yawning, evaluates leading theories on its purpose, and unpacks the phenomenon of contagious yawning with insights from neuroscience and behavioral studies.

The Physiology of a Yawn

A yawn is more than just an open mouth and a deep breath. It’s a coordinated physiological event involving multiple systems. A typical yawn begins with a slow inhalation through the mouth, lasting 5–10 seconds, followed by a brief pause and then a quicker exhalation. During this process, facial muscles stretch, the eardrums tense, and the heart rate may briefly increase.

Neurologically, yawning is regulated by a network in the brainstem—the region responsible for basic life-sustaining functions like breathing and heart rate. Key neurotransmitters involved include dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine, and nitric oxide. Studies show that stimulating dopamine pathways can trigger yawning, while certain medications that block dopamine reduce yawning frequency.

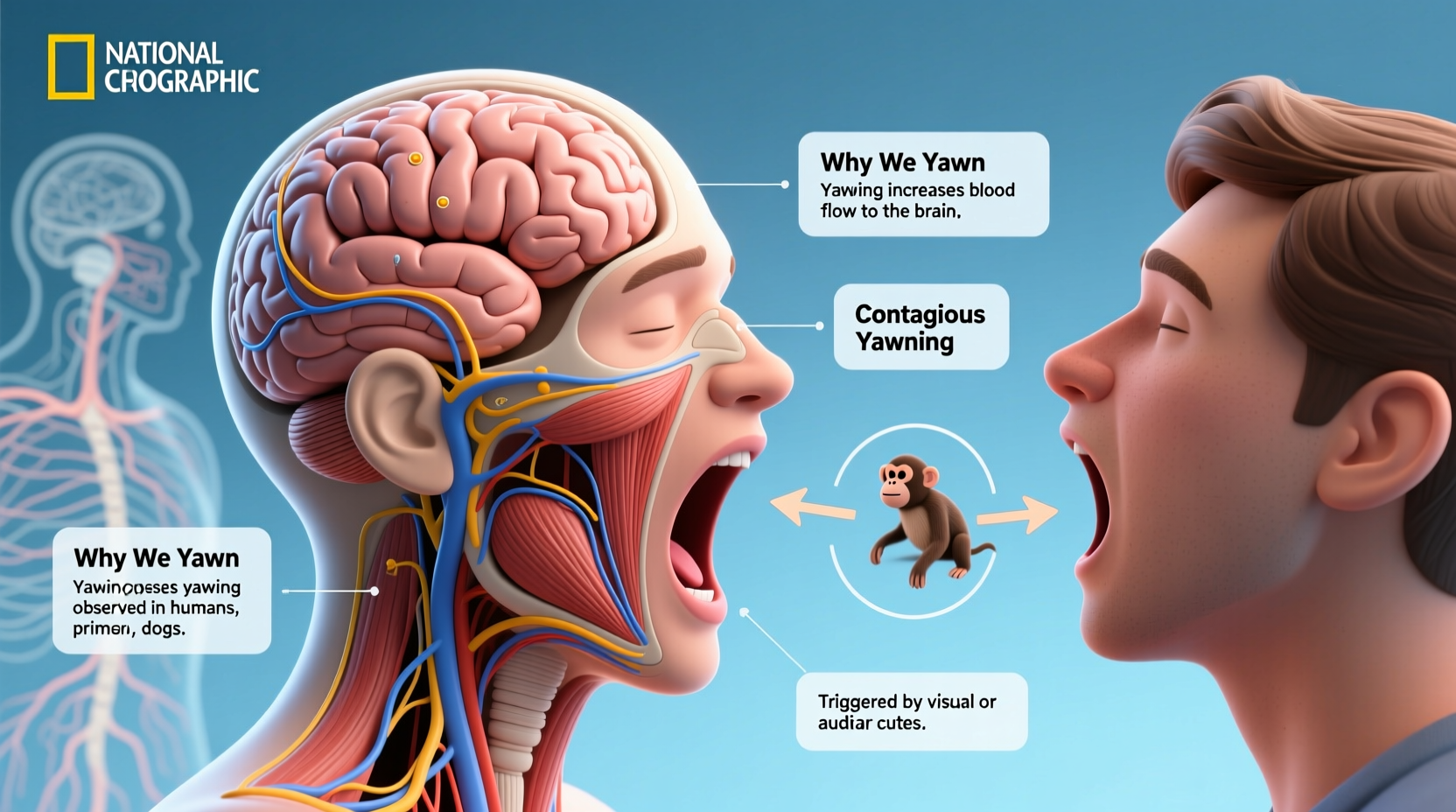

One prominent theory suggests that yawning helps regulate brain temperature. When the brain heats up due to fatigue, boredom, or sleepiness, yawning may act as a cooling mechanism. The deep inhalation draws cooler air into the nasal and oral cavities, increasing blood flow to the skull and promoting heat exchange. Research using thermal imaging has shown that people are more likely to yawn in ambient temperatures conducive to heat dissipation, supporting this thermoregulatory hypothesis.

Possible Biological Functions of Yawning

While no single explanation fully accounts for all instances of yawning, several compelling theories attempt to explain its biological role:

- Brain Cooling: As mentioned, yawning may help maintain optimal brain temperature. Overheating impairs cognitive function, so yawning could be a natural way to preserve mental clarity during prolonged focus or drowsiness.

- State Regulation: Yawning often occurs during transitions between states—waking to sleeping, boredom to alertness. It may serve as a physiological “reset” signal, helping the body shift modes by altering heart rate, muscle tone, and cortical arousal.

- Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Balance: Though once widely believed, this theory—that yawning increases oxygen intake—is now largely discounted. Controlled studies show no significant change in blood oxygen levels before or after yawning.

- Pressure Equalization: The stretching of jaw muscles and opening of the Eustachian tubes during a yawn may help equalize pressure in the ears, particularly during altitude changes, similar to swallowing or chewing.

Interestingly, fetuses begin yawning as early as 11 weeks gestation, long before they breathe air. This suggests yawning may play a role in prenatal development, possibly aiding in the maturation of motor circuits or neural networks related to facial movement and respiration.

Why Is Yawning Contagious?

Of all yawning’s quirks, none is more socially intriguing than its contagious nature. Seeing, hearing, or even reading about someone yawning can trigger the same response in others. This phenomenon isn’t unique to humans—chimpanzees, dogs, and even birds exhibit contagious yawning under certain conditions.

Contagious yawning appears linked to empathy and social bonding. Functional MRI studies show that when people observe others yawning, brain regions associated with imitation and emotional processing—such as the prefrontal cortex and the mirror neuron system—become active. These areas are crucial for understanding others’ intentions and emotions.

“Contagious yawning is not just mimicry; it reflects our ability to resonate with others emotionally. It’s a subtle but powerful form of nonverbal connection.” — Dr. Sarah McIntosh, Cognitive Neuroscientist, University of Edinburgh

Research supports a strong correlation between empathy levels and susceptibility to contagious yawning. Children under four years old rarely catch yawns, coinciding with the developmental stage when theory of mind—the ability to understand others' mental states—is still emerging. Individuals with autism spectrum disorder, which often involves differences in social cognition, also tend to yawn less contagiously than neurotypical individuals.

However, not everyone experiences contagious yawning equally. Approximately 40–60% of adults are susceptible, with variability influenced by personality traits, mood, and even time of day. Some studies suggest that people are more likely to \"catch\" yawns from those they’re emotionally close to—family members or friends—than from strangers, further reinforcing the social bond theory.

Comparative Table: Do’s and Don’ts of Yawning in Social Contexts

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Cover your mouth discreetly when yawning in public | Suppress a yawn forcefully—it can cause ear pressure or jaw strain |

| Use a quiet sigh or stretch if trying to stay alert in meetings | Blame yourself for yawning; it’s a natural reflex, not rudeness |

| Recognize contagious yawning as a sign of group synchrony | Assume someone is bored just because they yawned |

| Stay hydrated and take breaks if yawning frequently during work | Ignore excessive yawning—it may signal sleep deprivation or health issues |

Mini Case Study: The Office Meeting Effect

In a mid-morning strategy meeting at a tech startup, one team member stifled a yawn behind her hand. Within two minutes, three others had yawned—two openly, one subtly covering his mouth. The facilitator paused, joking, “Is this presentation that tiring?” Laughter followed, but the pattern was telling.

Later analysis revealed that the yawning cluster occurred among team members with high interpersonal trust and collaborative history. Two who didn’t yawn were new hires who joined the company only weeks prior. This aligns with research showing that familiarity enhances contagious yawning. The shared yawn didn’t reflect disinterest—it signaled unconscious social alignment, a subtle cue of engagement rather than detachment.

After adjusting room lighting and incorporating short stretch breaks, the team reported improved focus and fewer fatigue-related yawns. The incident became a talking point in their wellness workshop, highlighting how understanding biological cues can improve workplace culture.

Step-by-Step Guide to Managing Excessive Yawning

Frequent yawning isn’t always about tiredness. If you find yourself yawning more than usual, consider these steps to identify and address potential causes:

- Assess Sleep Quality: Track your sleep duration and consistency for a week. Are you getting 7–9 hours? Poor sleep is the most common cause of excessive yawning.

- Evaluate Your Environment: Is the room stuffy, warm, or poorly ventilated? Open a window or step outside for fresh air to stimulate alertness.

- Check Medications: Some antidepressants, antihistamines, and sedatives list yawning as a side effect. Consult your doctor if you suspect a drug-related cause.

- Monitor for Medical Conditions: Excessive yawning can be linked to migraines, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, or cardiovascular issues. If yawning persists without clear reason, seek medical evaluation.

- Practice Mindful Breathing: Replace passive yawning with intentional diaphragmatic breathing—inhale deeply for 4 counts, hold for 4, exhale for 6. This can boost oxygenation and mental clarity.

Expert Insight: The Evolutionary Angle

Some researchers argue that yawning evolved as a form of nonverbal communication within social groups. In ancestral environments, synchronized yawning might have helped coordinate rest periods across a tribe, ensuring collective vigilance and safety.

“In early human groups, yawning could have been a silent signal: ‘I’m shifting into rest mode.’ When others caught the yawn, it created group cohesion around sleep-wake cycles.” — Dr. Alan Pierce, Evolutionary Biologist, Stanford University

This theory gains support from observations in social animals. For example, chimpanzees are more likely to yawn contagiously after seeing a dominant group member yawn, suggesting a hierarchical signaling component. Similarly, dogs yawn more in response to their owner’s yawn than to a stranger’s, indicating emotional attachment plays a role.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you die from holding in a yawn?

No, you cannot die from suppressing a yawn. However, consistently inhibiting natural reflexes may lead to temporary discomfort, such as jaw tension or increased ear pressure. While not dangerous, allowing natural bodily responses is generally healthier than chronic suppression.

Why do I yawn when I’m nervous?

Nervous yawning is surprisingly common. Stress activates the vagus nerve, which connects the brain to the heart and digestive tract. Overstimulation of this nerve can trigger yawning as part of the body’s effort to regulate autonomic function. Athletes, performers, and public speakers often report yawning before competitions or presentations.

Are there animals that don’t yawn?

True yawning—defined by the stereotyped mouth opening, deep inhalation, and physiological sequence—has been observed in nearly all vertebrates, including reptiles, birds, and fish. While some species may not exhibit contagious yawning, the basic motor pattern appears evolutionarily conserved, underscoring its fundamental biological importance.

Conclusion: Embracing the Yawn

Yawning is far more than a sign of fatigue or boredom. It’s a complex, biologically rooted behavior intertwined with brain regulation, social connection, and evolutionary adaptation. Whether cooling the mind, syncing group rhythms, or silently expressing empathy, yawning serves functions both physiological and psychological.

Understanding why we yawn—and why it spreads like wildfire in a classroom or boardroom—can foster greater self-awareness and compassion. Instead of suppressing yawns out of politeness, we might reframe them as natural signals worth listening to. They remind us when our brains need a reset, when our bodies crave rest, and when our social circuits are actively engaged.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?