Yawning is one of the most universal human behaviors—so common that we rarely stop to question it. Yet beneath its simplicity lies a complex neurological phenomenon that scientists have studied for decades. From newborns in the womb to animals across species, yawning occurs widely, but its purpose remains partially enigmatic. While many assume yawning signals fatigue or boredom, research suggests deeper physiological and social functions. Even more intriguing is the fact that seeing someone else yawn often triggers the same urge—an effect rooted in our brain’s wiring. This article explores the science behind yawning, examines why it might be contagious, and unpacks the neural networks involved in this involuntary reflex.

The Physiology of Yawning: More Than Just Tiredness

At its core, a yawn is a stereotyped action involving a slow opening of the mouth, deep inhalation, brief pause, and exhalation. It typically lasts between 5 and 10 seconds and is accompanied by stretching of the eardrums, increased heart rate, and muscle activation in the face, neck, and thorax. Despite its ubiquity, yawning isn't fully understood—but several compelling theories attempt to explain its biological role.

One leading hypothesis is the brain cooling theory. Researchers at Binghamton University have proposed that yawning helps regulate brain temperature. The brain operates optimally within a narrow thermal range, and when it overheats—due to sleepiness, stress, or prolonged concentration—yawning may act as a natural radiator. The deep breath draws cool air into the lungs, which then passes over blood vessels in the sinus cavities, cooling the blood before it reaches the brain. Studies using infrared thermography have shown that people yawn more frequently when ambient temperatures are conducive to heat exchange (between 20°C and 24°C), supporting this model.

Another theory ties yawning to arousal regulation. Before major transitions—waking up, falling asleep, or shifting attention—yawning increases alertness by stimulating the sympathetic nervous system. This jolt enhances circulation, oxygen intake, and mental focus. Athletes often yawn before competition; soldiers before missions. These aren’t signs of drowsiness but rather neurochemical preparation for action.

Is Yawning Contagious? The Social Neuroscience Behind Mirror Responses

Most people experience it: someone nearby yawns, and suddenly you feel an irresistible urge to do the same. This phenomenon, known as contagious yawning, affects about 40% to 70% of adults. What makes it fascinating is that it doesn’t occur in infancy and appears to be linked to empathy and social bonding.

Neuroimaging studies reveal that contagious yawning activates regions associated with imitation and theory of mind—the ability to understand others’ mental states. Key areas include the prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and the temporoparietal junction. These regions light up not just during mimicry but also when interpreting emotions and intentions.

A landmark study published in *Current Biology* found that children under four years old—who are still developing empathetic cognition—rarely catch yawns from others. Similarly, individuals on the autism spectrum, who may struggle with social cue interpretation, show lower rates of contagious yawning. This correlation supports the idea that the reflex is not merely mechanical but socially modulated.

“Contagious yawning appears to be a window into our capacity for empathy. It reflects how deeply wired we are for connection.” — Dr. Steven Platek, Cognitive Neuroscientist, Drexel University

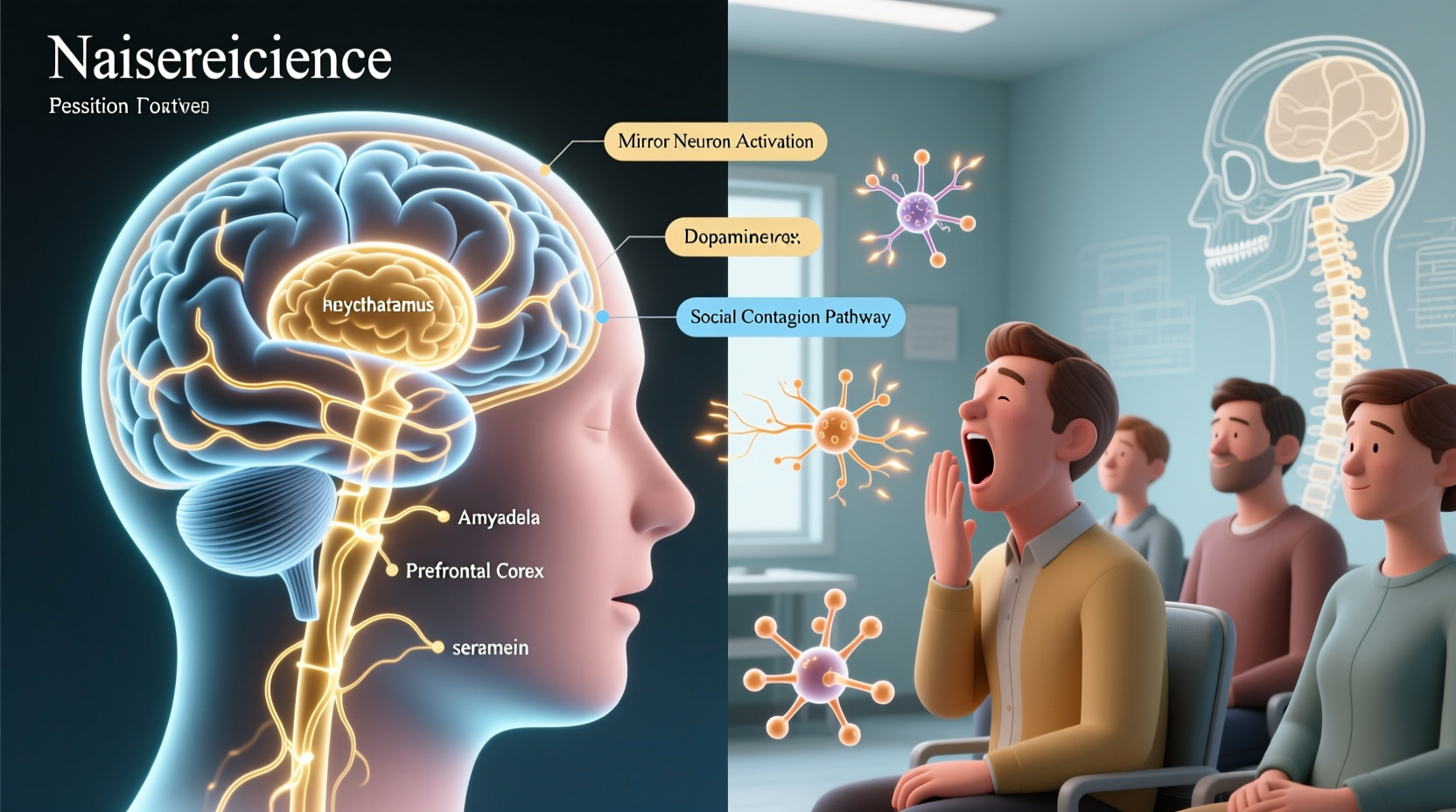

The Role of Mirror Neurons and Brain Connectivity

The discovery of mirror neurons in the 1990s revolutionized our understanding of social behavior. Found primarily in the premotor and parietal cortices, these neurons fire both when we perform an action and when we observe someone else doing it. They are believed to underpin imitation, language acquisition, and emotional resonance.

When it comes to yawning, mirror neuron systems likely play a central role. Observing a yawn activates these circuits, priming the motor cortex to replicate the movement—even without conscious intent. However, not everyone responds equally. Research shows that familiarity influences contagion: people are more likely to \"catch\" yawns from friends and family than strangers. One study found that participants mirrored yawns from close relatives 50% more often than those from unfamiliar individuals, suggesting that emotional closeness amplifies neural mirroring.

Interestingly, dogs also exhibit contagious yawning toward humans—a rare cross-species response. In experiments, dogs yawned significantly more after watching their owners yawn compared to strangers, reinforcing the bond-based nature of the phenomenon.

Timeline: How a Contagious Yawn Unfolds in the Brain

- Visual Input (0–500 ms): The observer sees another person begin to yawn. Visual cortex processes facial cues, particularly mouth opening and eye widening.

- Mirror Neuron Activation (500–1200 ms): Premotor and inferior frontal regions activate, simulating the observed action internally.

- Emotional Resonance (1–2 s): Temporoparietal and cingulate areas assess social relevance, increasing likelihood of replication if the person is familiar or trusted.

- Motor Preparation (2–3 s): Supplementary motor area prepares the muscles involved in yawning.

- Execution (3–5 s): The full yawn unfolds—mouth opens, deep breath taken, followed by exhalation and muscle relaxation.

This sequence illustrates how a simple visual stimulus can cascade through multiple brain networks, blending perception, emotion, and motor control into a seamless reflex.

What Conditions Affect Yawning Frequency?

While yawning is normal, excessive yawning can signal underlying health issues. Understanding deviations from typical patterns provides insight into both neurological and systemic function.

| Condition | Effect on Yawning | Possible Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep deprivation | Increased frequency | Brain attempts to cool down and boost alertness |

| Migraine attacks | Pre-attack surge | Changes in brainstem activity affecting thermoregulation |

| Epilepsy (temporal lobe) | Ictal yawning (during seizures) | Irritation of limbic structures near amygdala |

| Multiple sclerosis | Excessive, unexplained yawning | Demyelination affecting autonomic pathways |

| Medications (SSRIs) | Side effect in some patients | Serotonin modulation influencing brainstem centers |

In clinical settings, persistent yawning lasting weeks—especially without fatigue—should prompt evaluation for neurological causes. For example, damage to the brainstem or hypothalamus can disrupt autonomic control, leading to abnormal yawning episodes.

Practical Implications: Harnessing the Science of Yawning

Understanding yawning isn’t just academic—it has real-world applications in education, workplace performance, and mental health.

- In classrooms, teachers can recognize yawning not as disinterest but as a sign of cognitive load or need for breaks.

- Workplaces aiming to improve focus might incorporate short pauses after mentally taxing tasks, allowing natural arousal resets via yawning or stretching.

- Therapists working with autistic individuals may use yawning studies to better understand social engagement thresholds.

Mini Case Study: The Air Traffic Controller Shift

An air traffic control center in Germany implemented a pilot program to reduce errors during night shifts. Supervisors noticed clusters of yawning among staff between 2:00 AM and 4:00 AM—coinciding with peak accident risk windows. Instead of discouraging yawning, they introduced scheduled 5-minute “reset breaks” every two hours, encouraging controlled breathing and light movement.

Over six months, error rates dropped by 27%, and self-reported alertness improved significantly. The change acknowledged yawning not as laziness but as a biologically honest signal of changing arousal states. By aligning workflow with natural physiology, the facility enhanced safety without altering staffing or technology.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do I yawn even when I’m not tired?

Yawning serves multiple functions beyond fatigue relief. It can help regulate brain temperature, increase alertness during transitions, or respond to changes in oxygen levels. Stress, boredom, or concentration can all trigger yawning independently of sleepiness.

Can you suppress a contagious yawn?

Attempts to suppress a yawn may delay it slightly, but the urge usually persists. Functional MRI scans show that even when people resist yawning, their brains still activate the associated neural circuits. Suppression doesn’t eliminate the internal process—it only prevents outward expression.

Do all animals yawn contagiously?

No. Contagious yawning has been documented in chimpanzees, bonobos, wolves, dogs, and budgerigars—but not in most reptiles, birds, or rodents. Its presence correlates with social complexity and empathetic abilities, suggesting it evolved in species reliant on group coordination.

Checklist: Understanding and Responding to Yawning

Use this checklist to interpret and respond appropriately to yawning—yours or others’:

- ✅ Assess context: Is the person sleepy, stressed, or highly focused?

- ✅ Consider environment: Is the room warm? Poor ventilation may increase yawning due to CO₂ buildup.

- ✅ Evaluate frequency: More than once every few minutes could indicate fatigue or medical concern.

- ✅ Recognize social cues: In group settings, contagious yawning may reflect shared mental states.

- ✅ Don’t stigmatize: Avoid assuming yawning equals disengagement; it may signal effortful concentration.

Conclusion: Embracing the Yawn as a Window Into the Mind

Far from being a mere sign of boredom, yawning is a sophisticated neurobiological reflex intertwined with brain health, social cognition, and physiological balance. Its contagious nature reveals the depth of our innate connectivity—how seeing another person’s state can instantly alter our own. As neuroscience continues to decode the mechanisms behind this everyday act, we gain greater appreciation for the subtle ways our bodies maintain equilibrium and foster empathy.

Next time you feel a yawn coming on—or see one ripple through a meeting room—pause and reflect. That simple stretch may be your brain recalibrating, your body preparing, or your mind resonating with someone else’s experience. In a world increasingly driven by digital interaction, the humble yawn reminds us of the enduring power of biological synchrony.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?