Yawning is one of the most universal human behaviors—experienced from infancy to old age, across cultures and even species. It’s often associated with tiredness or boredom, yet people also yawn before stressful events like athletic competitions or public speaking. Despite its ubiquity, the science behind yawning remains surprisingly complex. More intriguing still is the phenomenon of contagious yawning: seeing, hearing, or even thinking about a yawn can trigger one in ourselves. This article explores the neuroscience behind yawning, investigates its possible evolutionary roots, and explains why it might be one of the most socially synchronized acts humans perform.

The Physiology of Yawning: What Happens in the Brain?

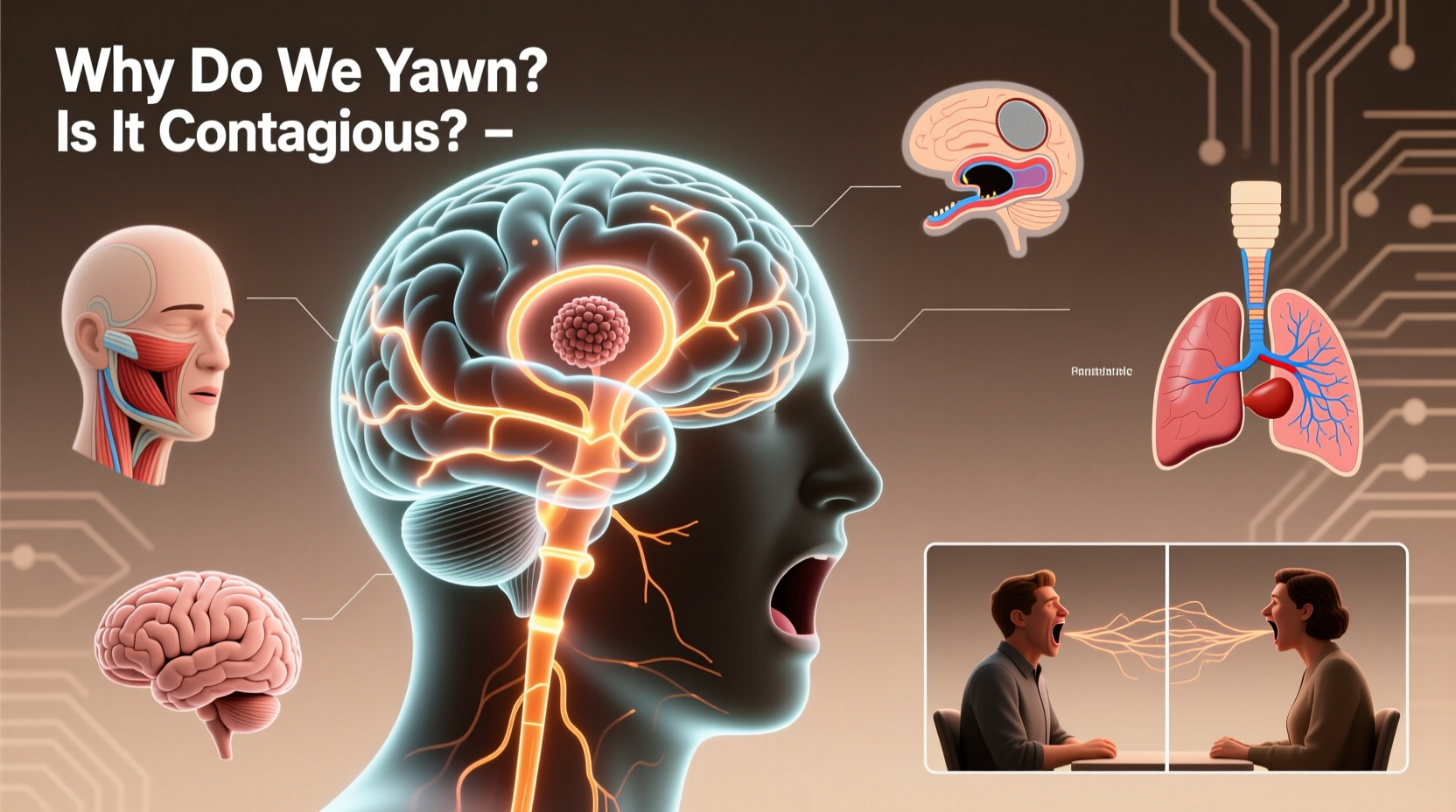

A yawn is a reflex involving a deep inhalation through an open mouth, followed by a brief pause and a slower exhalation. The process engages multiple systems: respiratory, muscular, and neurological. Neurologically, yawning begins in the brainstem—the primitive part of the brain that controls automatic functions like breathing, heart rate, and sleep-wake cycles.

Specifically, the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus plays a central role. This region releases neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine, and nitric oxide, all of which have been shown to modulate yawning frequency. For instance, dopamine agonists (drugs that stimulate dopamine receptors) are known to increase yawning, while antagonists reduce it. This suggests that the dopaminergic system is deeply involved in initiating the yawn reflex.

Interestingly, yawning may serve a thermoregulatory function. Research by Gallup and Gallup (2007) proposes that yawning helps cool the brain. The deep intake of air pulls cooler blood into the maxillary sinuses, while the stretching of jaw muscles increases blood flow to the skull. This mechanism could help maintain optimal brain temperature, especially during transitions between sleep and wakefulness or after mental exertion.

Why Do We Yawn? Major Theories Explained

Despite decades of research, no single theory fully explains why we yawn. However, several well-supported hypotheses offer insight into this mysterious behavior.

1. Brain Cooling Hypothesis

This theory posits that yawning regulates brain temperature. Studies show yawning frequency increases when ambient temperatures approach body temperature, but decreases when it's too hot or too cold. Animals like birds and reptiles yawn more frequently in warmer climates, supporting the idea that yawning serves as a physiological coolant.

2. State Change Theory

Yawning often occurs during transitions—waking up, falling asleep, or shifting focus. It may help increase alertness by stimulating circulation and oxygen intake. Functional MRI studies show increased activity in areas related to arousal and attention just before and after a yawn, suggesting it prepares the brain for a change in behavioral state.

3. Evolutionary Vestige

Some scientists believe yawning originated as a threat display in ancestral primates. An open mouth showing teeth could signal dominance or readiness to act. While modern humans don’t use yawning aggressively, the motor pattern may persist due to its integration into social and physiological regulation.

4. Oxygen-Carbon Dioxide Regulation (Debunked)

One long-standing myth claims yawning increases oxygen levels or reduces carbon dioxide. However, experiments exposing subjects to high-oxygen or high-CO₂ environments show no change in yawning frequency. This theory has largely been discredited by modern neuroscience.

“Yawning isn't about oxygen—it’s about brain state regulation and social connection.” — Dr. Robert Provine, neuroscientist and author of *Curious Behavior*

The Contagious Nature of Yawning: A Window into Empathy

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of yawning is its contagiousness. Around 40–60% of adults will yawn within minutes of seeing someone else yawn—even if they’re reading about it. This effect works across sensory modalities: watching a video, hearing a yawn, or imagining one can all trigger the response.

Neuroimaging studies reveal that contagious yawning activates regions tied to empathy and social cognition, including the posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, and orbitofrontal cortex. These areas are part of the brain’s “mirror neuron system,” which fires both when we perform an action and when we observe someone else doing it.

Mirror neurons may explain why individuals with higher empathy scores are more susceptible to contagious yawning. Conversely, children under four years old—who haven’t fully developed theory of mind—rarely catch yawns. Similarly, people on the autism spectrum, particularly those with lower social responsiveness, show reduced susceptibility to contagious yawning, though not always absent.

Contagious Yawning Across Species

Humans aren’t alone in this. Chimpanzees, dogs, bonobos, and wolves also exhibit contagious yawning—especially toward familiar individuals. In one study, dogs were significantly more likely to yawn after hearing their owner yawn than a stranger’s, suggesting a bond-based component to the response.

When Yawning Signals Something Else: Medical and Psychological Insights

While occasional yawning is normal, excessive yawning can indicate underlying health issues. Frequent, unexplained yawning—sometimes dozens per hour—may point to:

- Sleep disorders: Narcolepsy, sleep apnea, or insomnia disrupt rest, leading to chronic fatigue and increased yawning.

- Neurological conditions: Epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, or brain tumors affecting the brainstem can alter yawning patterns.

- Vasovagal reactions: Before fainting or during migraines, some patients report prolonged yawning episodes due to changes in blood pressure or cranial nerve activity.

- Medication side effects: SSRIs, dopamine agonists, and antihistamines are known to increase yawning frequency.

If excessive yawning is accompanied by dizziness, chest pain, or cognitive changes, medical evaluation is recommended. Doctors may assess sleep quality, neurological function, or medication regimens to identify root causes.

Step-by-Step: How to Reduce Unwanted Yawning in Public

For professionals, students, or speakers, frequent yawning can be misinterpreted as disinterest or fatigue. While you can’t eliminate yawning entirely, these steps can help minimize disruptive episodes:

- Stay hydrated: Dehydration thickens blood and reduces oxygen delivery, potentially triggering yawning. Drink water consistently throughout the day.

- Optimize sleep hygiene: Aim for 7–9 hours of uninterrupted sleep. Maintain a regular bedtime and avoid screens before bed.

- Control room temperature: Overheated environments increase brain temperature and yawning likelihood. Use fans or open windows when possible.

- Practice diaphragmatic breathing: Deep belly breaths increase alertness and stabilize CO₂ levels without triggering a yawn reflex.

- Engage your jaw subtly: Gently clenching molars or chewing gum can inhibit the jaw-stretching motion that precedes a yawn.

Do’s and Don’ts of Yawning Etiquette and Health

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Cover your mouth with your elbow or hand when yawning in public | Suppress yawns forcefully—they’re a physiological need |

| Use yawning as a cue to take breaks during long tasks | Assume others are bored just because they yawn |

| Monitor frequency if you suspect a sleep or neurological issue | Ignore persistent excessive yawning with other symptoms |

| Embrace natural rhythms—yawning upon waking is normal | Feel embarrassed—everyone yawns, and it’s biologically essential |

Real-World Example: The Boardroom Yawn Chain

In a recent corporate strategy meeting, a senior executive began the session with a noticeable yawn. Within ten minutes, three other attendees had yawned—two visibly covering their mouths, one stifling it. Later, one participant admitted feeling unusually tired, while another said, “I wasn’t sleepy at all, but when I saw him yawn, I couldn’t stop myself.”

This anecdote illustrates how contagious yawning operates beneath conscious awareness. The initial yawn acted as a subtle social signal, possibly interpreted as fatigue or stress, prompting others to unconsciously align their physiological states. In leadership settings, such nonverbal cues can influence group dynamics, either fostering shared alertness or inadvertently spreading lethargy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you stop yourself from yawning?

You can temporarily suppress a yawn, but not indefinitely. The urge is driven by deep brain mechanisms and will eventually override conscious control. Instead of suppression, address root causes like poor sleep or dehydration.

Why do I yawn when I’m nervous?

Nervous yawning is common before performances, exams, or presentations. It’s thought to regulate arousal—calming the nervous system by increasing heart rate variability and oxygen flow. Essentially, the body uses yawning to balance stress and alertness.

Are babies affected by contagious yawning?

No—contagious yawning typically emerges around age four or five, coinciding with the development of empathy and social awareness. Infants yawn frequently (up to 40 times daily), but not in response to others’ yawns.

Conclusion: Embracing the Yawn as a Biological and Social Signal

Yawning is far more than a sign of sleepiness. It’s a finely tuned neurophysiological mechanism that helps regulate brain temperature, shift mental states, and even strengthen social bonds. Its contagious nature reveals a deep-seated human capacity for empathy and synchronization—echoes of our evolutionary past playing out in everyday interactions.

Understanding the science behind yawning empowers us to interpret it more accurately: not as rudeness or disengagement, but as a complex biological signal. Whether you're trying to stay alert during a long day or wondering why your dog yawned after you did, remember—this simple act connects us to our brains, our bodies, and each other.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?