Yawning is one of the most universal human behaviors—everyone does it, from newborns to the elderly. It’s often linked with fatigue, boredom, or sleepiness. But why exactly do we yawn when tired? While many assume it's about oxygen intake or a sign of laziness, modern neuroscience suggests a far more fascinating explanation: the brain cooling theory. This idea reframes yawning not as a passive reflex, but as an active biological mechanism to regulate brain temperature. In this article, we’ll break down the science behind this theory in clear, accessible terms and explore how something as simple as a yawn plays a crucial role in keeping our brains functioning optimally.

The Physiology of Yawning

At its core, yawning is a deep, involuntary inhalation that begins with a wide opening of the mouth, followed by a slow, extended breath in, a brief pause, and then a slower exhalation. It typically lasts around 5 to 10 seconds and is often accompanied by stretching, especially in the arms and upper body. What makes yawning unique is that it’s contagious—one person’s yawn can trigger a chain reaction among others nearby, even if they’re not tired.

Despite being common, yawning has long puzzled scientists. For decades, the prevailing assumption was that yawning increased oxygen levels in the blood and reduced carbon dioxide, thereby helping us stay alert. However, research conducted in the 1980s debunked this idea. Controlled studies showed that altering oxygen and CO₂ levels in the bloodstream had no significant effect on yawning frequency. This led researchers to look for alternative explanations—ones rooted not in respiration, but in thermoregulation.

The Brain Cooling Theory Explained

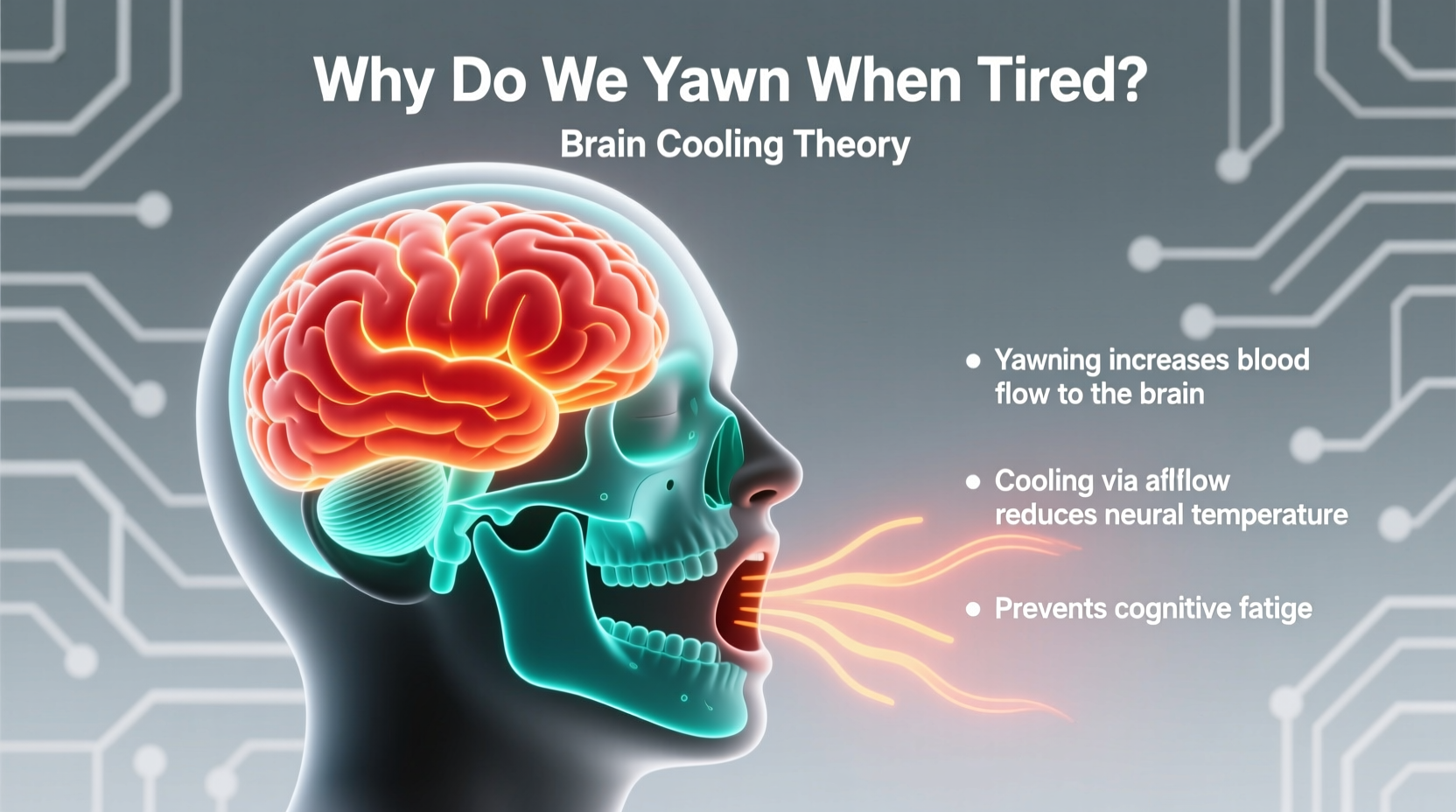

The brain cooling theory proposes that yawning functions as a built-in radiator system for the brain. The human brain operates best within a narrow temperature range—just slightly below core body temperature. When brain temperature rises, cognitive performance declines, sleepiness increases, and alertness drops. This is especially noticeable during prolonged mental activity, stress, or fatigue.

According to researchers like Dr. Andrew Gallup, a leading expert on yawning behavior, yawning helps cool the brain through two main mechanisms:

- Increased Blood Flow: The deep inhalation during a yawn creates pressure changes in the thoracic cavity, which enhances venous return—the flow of blood back to the heart. This, in turn, boosts circulation through the brain, bringing cooler arterial blood from the body’s surface.

- Cooling via Nasal Inhalation: As you inhale deeply during a yawn, air passes through the nasal and oral cavities, which are richly supplied with blood vessels. The cool air absorbs heat from these vessels before reaching the brain, effectively lowering cerebral temperature.

In essence, yawning acts like a “reset button” for brain temperature. It doesn’t just signal tiredness—it actively combats it by restoring optimal neural conditions.

Why Yawning Increases When Tired

Fatigue is strongly associated with elevated brain temperature. During prolonged wakefulness, metabolic activity in the brain generates heat faster than it can be dissipated. This buildup contributes to the groggy, unfocused feeling we experience when exhausted. Yawning becomes more frequent during these times because the brain is essentially triggering its own cooling protocol.

Studies have shown that people yawn more frequently in the hours before sleep and upon waking—both periods when brain temperature regulation is critical. Interestingly, yawns also increase during transitions in alertness, such as when shifting from focused work to relaxation, or vice versa. These shifts require rapid adjustments in brain metabolism and temperature, making yawning a timely physiological response.

Supporting Evidence for the Brain Cooling Model

The brain cooling theory isn’t just speculative—it’s supported by a growing body of experimental evidence across species and environments.

In one notable study, researchers observed that participants yawned significantly less when holding a cold pack to their forehead compared to a warm one. Conversely, exposure to higher ambient temperatures increased yawning frequency, but only up to a point. When external temperatures exceed body temperature, yawning decreases—because inhaling hot air would further heat the brain instead of cooling it. This inverted U-shaped pattern aligns perfectly with thermoregulatory predictions.

Animal studies reinforce this model. Birds, reptiles, and mammals all exhibit yawning behaviors linked to thermal regulation. For example, rats yawn more frequently when their brain temperature rises, and blocking certain thermoregulatory pathways reduces yawning. Even fish display yawn-like movements under conditions of thermal stress.

“Yawning is not merely a sign of drowsiness—it’s a physiological mechanism to maintain brain homeostasis.” — Dr. Andrew Gallup, Evolutionary Psychologist, SUNY College at Oneonta

Contagious Yawning and Social Thermoregulation

One of the most intriguing aspects of yawning is its contagious nature. Seeing, hearing, or even reading about someone else yawning can trigger the reflex. While this phenomenon remains partially mysterious, some researchers believe it may have evolved as a form of social synchronization.

From a brain cooling perspective, contagious yawning could serve a group-level function. In ancestral human groups, synchronized yawning might have helped coordinate rest cycles or enhance vigilance during transitions between activity states. Some studies suggest that individuals with stronger social empathy are more susceptible to contagious yawning, hinting at a link between emotional connection and shared physiological rhythms.

Debunking Common Myths About Yawning

Despite scientific advances, several misconceptions about yawning persist. Let’s clarify the facts:

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| Yawning brings more oxygen to the brain. | No controlled studies support this. Oxygen levels don’t correlate with yawning frequency. |

| Only humans and dogs yawn contagiously. | Chimpanzees, bonobos, wolves, and even budgerigars show contagious yawning. |

| Excessive yawning means poor fitness or laziness. | It may indicate underlying issues like sleep disorders, migraines, or neurological conditions. |

| Babies don’t yawn until they’re older. | Fetuses yawn in the womb as early as 11 weeks gestation. |

Practical Implications: Listening to Your Yawns

Understanding yawning as a brain-cooling mechanism changes how we interpret it. Instead of viewing it as a sign of rudeness or disinterest, we can treat it as valuable biofeedback—a signal that your brain needs a moment to recalibrate.

When Yawning Signals Something Else

While occasional yawning is normal, excessive yawning—defined as more than once per minute over a sustained period—can sometimes point to medical concerns. Conditions associated with abnormal yawning include:

- Sleep disorders (e.g., insomnia, sleep apnea)

- Migraine attacks

- Epilepsy or brain injuries

- Side effects of medications (especially antidepressants)

- Cardiovascular issues (rarely, yawning can precede a heart attack due to vagus nerve stimulation)

If frequent yawning disrupts daily life or occurs without fatigue, consulting a healthcare provider is advisable.

Actionable Checklist: Supporting Natural Brain Cooling

You can’t stop yawning—and you shouldn’t want to—but you can support your brain’s natural ability to regulate temperature. Use this checklist to maintain optimal cognitive function:

- Stay hydrated: Dehydration impairs thermoregulation.

- Take breaks in cool environments: Especially after intense mental work.

- Breathe through your nose: Enhances air cooling before it reaches the brain.

- Get quality sleep: Prevents chronic brain overheating.

- Avoid prolonged screen time without breaks: Mental strain raises brain temperature.

- Use fans or open windows: Ambient airflow aids passive cooling.

- Practice mindfulness or light stretching: Reduces stress-induced heat buildup.

Mini Case Study: The Student Pulling an All-Nighter

Consider Maria, a college student preparing for finals. She’s been studying for 12 hours straight, fueled by coffee and energy drinks. Around midnight, she notices she’s yawning constantly—every few minutes. She interprets this as her body begging for sleep, which is true, but there’s more beneath the surface.

Her prefrontal cortex has been highly active, processing complex information. Metabolic waste and heat have accumulated. Her brain temperature has risen above optimal levels, impairing concentration. Each yawn is an attempt to cool down and restore alertness. While caffeine provides a temporary stimulant effect, it doesn’t address the root issue: thermal overload.

Instead of pushing through, Maria steps outside for five minutes. The cool night air, combined with slow nasal breathing, helps lower her brain temperature. When she returns, she feels slightly sharper—not fully alert, but more capable of finishing her review. Her yawning decreases temporarily, illustrating how environmental cooling complements the body’s natural regulatory systems.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does yawning really cool the brain?

Yes, substantial evidence supports this. Studies using thermal imaging and behavioral observation show that yawning correlates with changes in brain temperature. Actions that enhance cooling (like nasal breathing or forehead cooling) reduce yawning, while heat exposure increases it—up to the point where ambient air is warmer than the body.

Why do I yawn more when I’m trying to stay awake?

Your brain is working hard to remain alert, increasing metabolic activity and heat production. Yawning is a compensatory mechanism to prevent overheating and maintain cognitive performance. It’s your body’s way of fighting fatigue on a physiological level.

Can I suppress yawning safely?

Occasionally, yes—but chronically suppressing yawns may interfere with natural thermoregulation. If you’re in a situation where yawning is inappropriate (e.g., a meeting), try discreet alternatives: sip cool water, breathe slowly through your nose, or gently press a cool object (like a water bottle) against your forehead.

Conclusion: Rethinking a Simple Reflex

Yawning is far more than a sign of tiredness or boredom. It’s a sophisticated, evolutionarily conserved mechanism designed to keep our brains cool, efficient, and ready for action. The brain cooling theory transforms our understanding of this everyday behavior from a quirky habit into a vital component of cognitive health.

By recognizing yawning as a signal of thermal regulation, we learn to respond with greater awareness—stepping into cooler spaces, hydrating properly, or simply allowing ourselves needed rest. Rather than masking fatigue with stimulants, we can work with our biology to sustain mental clarity naturally.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?