Yawning is one of the most universal yet mysterious behaviors humans—and many animals—share. It happens spontaneously, often in response to fatigue, boredom, or even seeing someone else yawn. While it may seem like a simple reflex, the act of yawning when tired is deeply rooted in biology, neurology, and evolutionary adaptation. Scientists have long studied this phenomenon not just as a sign of sleepiness, but as a complex physiological signal tied to brain function, temperature regulation, and social communication.

This article explores the science behind why we yawn when tired, examining the leading theories, neurological mechanisms, and practical implications. From brain thermoregulation to empathy-driven contagion, understanding yawning offers surprising insights into how our bodies manage fatigue and maintain cognitive performance.

The Physiology of Yawning: More Than Just a Deep Breath

At its most basic level, a yawn is an involuntary action involving a slow, deep inhalation through the mouth, followed by a brief pause and a rapid exhalation. This process stretches the jaw, increases heart rate, and floods the bloodstream with oxygen. But contrary to popular belief, yawning isn’t primarily about increasing oxygen intake or reducing carbon dioxide levels—a theory largely debunked by modern research.

Instead, scientists now believe that yawning plays a role in optimizing brain state and alertness. When we’re tired, our brains operate less efficiently. Neural networks slow down, attention wanes, and mental clarity diminishes. Yawning appears to counteract some of these effects by stimulating arousal and resetting neural activity.

The act engages multiple systems:

- Autonomic nervous system: Triggers changes in heart rate and respiration.

- Musculoskeletal system: Involves the jaw, diaphragm, and facial muscles.

- Cerebral circulation: Enhances blood flow and regulates brain temperature.

These coordinated responses suggest yawning is not merely a passive reaction to drowsiness, but an active mechanism for maintaining optimal brain function under fatigue.

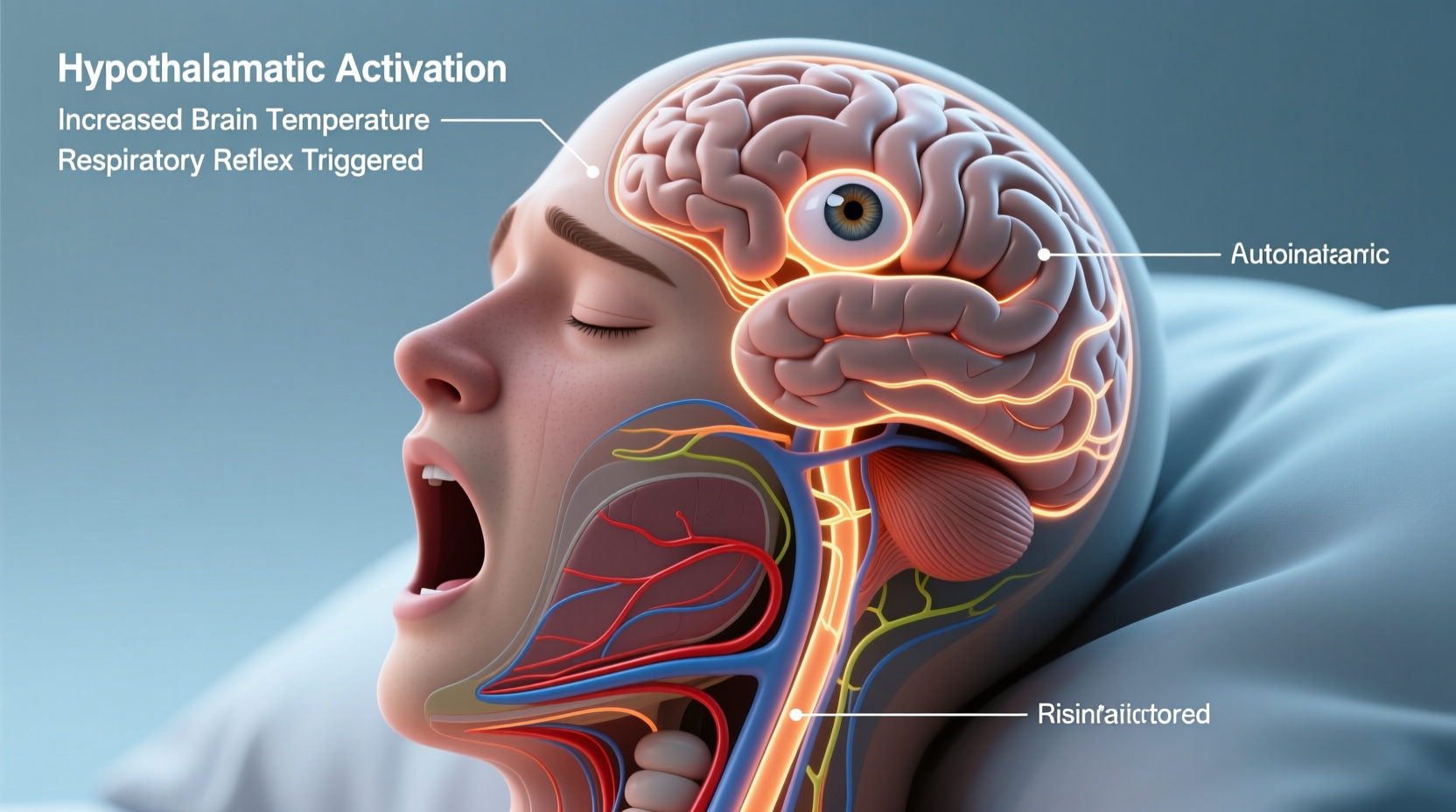

Brain Cooling Theory: The Leading Explanation for Fatigue-Induced Yawning

One of the most compelling scientific explanations for yawning when tired is the brain cooling hypothesis. Proposed by researchers at the University of Albany and supported by numerous studies, this theory suggests that yawning helps regulate brain temperature.

The brain functions best within a narrow thermal range. As we stay awake longer, metabolic activity generates heat, causing the brain’s temperature to rise slightly. Elevated brain temperature impairs cognitive processing, slows reaction times, and contributes to feelings of fatigue. Yawning acts as a natural cooling mechanism.

Here's how it works:

- A deep inhalation brings cool air into the nasal and oral cavities.

- This air passes over sinus networks adjacent to the brain, drawing heat away from blood vessels supplying the frontal lobes.

- Simultaneously, stretching the jaw increases blood flow to the skull, promoting convective heat loss.

- The result? A temporary drop in brain temperature—typically between 0.1°C and 0.5°C—enhancing alertness and mental efficiency.

A 2007 study published in Physiology & Behavior found that participants yawned significantly more when their foreheads were warmed (simulating internal heat buildup) compared to when cooled. This supports the idea that yawning responds directly to thermal shifts in the brain environment.

“Yawning is a thermoregulatory mechanism that fine-tunes brain temperature to optimize vigilance and cognitive performance.” — Dr. Gordon Gallup Jr., Evolutionary Psychologist, University at Albany

Neurochemical Triggers: Dopamine, Serotonin, and Fatigue Signals

Beyond temperature control, yawning is modulated by key neurotransmitters involved in arousal, mood, and sleep-wake cycles. Two primary chemicals implicated are dopamine and serotonin.

Dopamine, associated with motivation and wakefulness, has been shown to stimulate yawning at low doses. Conversely, high dopamine levels suppress it. This biphasic response explains why certain medications affecting dopamine pathways—like those used in Parkinson’s disease—can increase yawning frequency.

Serotonin, which promotes relaxation and sleep onset, also influences yawning. Increased serotonergic activity in the hypothalamus can trigger yawning episodes, especially during transitions between wakefulness and sleep.

Fatigue alters the balance of these neurotransmitters. As adenosine builds up during prolonged wakefulness, it inhibits dopamine release and enhances serotonin signaling, creating conditions favorable for yawning. This biochemical shift prepares the body for rest while using yawning as a transitional signal—alerting the system that homeostasis is shifting toward sleep.

| Neurotransmitter | Role in Yawning | Effect During Fatigue |

|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | Promotes arousal-induced yawning at low levels | Decreases, increasing yawning likelihood |

| Serotonin | Stimulates yawning via hypothalamic pathways | Increases, enhancing fatigue-related yawning |

| Adenosine | Indirectly promotes sleepiness and yawning | Accumulates, intensifying both fatigue and yawning |

This interplay shows that yawning isn’t random—it’s a finely tuned response embedded in our neurochemistry, serving as both a symptom and a regulatory tool during states of fatigue.

Contagious Yawning and Social Synchrony

Interestingly, yawning becomes more frequent not only when we’re tired, but also when we observe others doing it. This “contagious” aspect affects approximately 40–60% of adults and is linked to empathy and social bonding.

Functional MRI studies show that seeing someone yawn activates regions of the brain associated with mirror neurons and theory of mind—the ability to understand others’ mental states. People with higher emotional intelligence or stronger empathetic tendencies are more likely to \"catch\" yawns.

From an evolutionary standpoint, contagious yawning may have served a group coordination function. In ancestral environments, synchronized behavior—including sleep-wake cycles—could enhance group survival. If one member began showing signs of fatigue, others might follow suit, ensuring collective rest periods and shared vigilance patterns.

However, this social component weakens when we’re extremely tired. Paradoxically, while fatigue increases spontaneous yawning, it reduces susceptibility to contagious yawning. One explanation is that severe exhaustion narrows attentional focus inward, diminishing responsiveness to external social cues.

Mini Case Study: The Night Shift Worker

Consider Maria, a nurse working the overnight shift in a busy hospital. Around 3 a.m., she begins yawning frequently despite drinking coffee. Her team notices her yawning, but unlike earlier in the evening, no one else follows suit.

What’s happening? Maria’s brain temperature has risen due to prolonged wakefulness. Her dopamine levels are dropping, and adenosine is accumulating. Her spontaneous yawning serves as a biological attempt to cool her prefrontal cortex and maintain alertness during critical tasks.

Meanwhile, her coworkers—who started their shifts later—are still relatively alert. They don’t respond to her yawns because their brains aren’t primed for fatigue synchronization. Their mirror neuron systems remain active, but the internal physiological drive to yawn isn't present.

This scenario illustrates how yawning operates on two levels: individual regulation and social communication. Under extreme fatigue, self-preservation takes precedence over social mimicry.

Practical Implications: Using Yawning Awareness to Manage Energy

Recognizing yawning as a physiological signal—not just a nuisance—can help individuals better manage fatigue and improve daily performance. Rather than suppressing yawns out of politeness or habit, interpreting them as meaningful feedback allows for proactive adjustments.

Step-by-Step Guide: Responding to Fatigue-Related Yawning

- Notice the pattern: Track when you yawn most frequently—during meetings, after meals, or late at night.

- Assess context: Determine if yawning occurs alongside other fatigue signs (e.g., heavy eyelids, difficulty concentrating).

- Check environmental factors: Is the room warm? Poor ventilation raises core temperature, triggering more yawns.

- Take a cooling break: Step outside for fresh air, splash cool water on your face, or use a fan to lower ambient heat.

- Move your body: Light physical activity boosts circulation and mimics yawning’s arousal effects.

- Reevaluate sleep habits: Chronic fatigue-induced yawning may indicate insufficient or poor-quality sleep.

Yawning Do’s and Don’ts

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Use yawning as a cue to stretch or breathe deeply | Suppress every yawn; it may increase mental fog |

| Cool your face or neck when yawning frequently | Ignore repeated yawning during driving or operating machinery |

| Stay hydrated—dehydration worsens fatigue | Rely solely on caffeine to override yawning signals |

FAQ: Common Questions About Yawning and Fatigue

Why do I yawn even after getting enough sleep?

Even well-rested individuals yawn due to transient drops in alertness, changes in brain temperature, or shifts in posture (e.g., from standing to sitting). Boredom and low stimulation can also trigger yawning independent of sleep debt.

Can excessive yawning be a sign of a medical issue?

Yes. While occasional yawning is normal, persistent or unexplained yawning—especially if accompanied by dizziness, chest pain, or fatigue—may indicate underlying conditions such as sleep disorders, migraines, epilepsy, or cardiovascular issues. Consult a healthcare provider if yawning disrupts daily life.

Is it possible to stop being susceptible to contagious yawning?

You can reduce susceptibility by minimizing eye contact with yawners or focusing on non-facial features. However, attempts to suppress contagious yawning often fail because it’s an automatic, subconscious response tied to empathy circuits in the brain.

Conclusion: Listen to Your Body’s Subtle Signals

Yawning when tired is far more than a quirky bodily habit—it’s a sophisticated, evolutionarily refined mechanism designed to protect brain function and regulate alertness. By cooling the brain, adjusting neurotransmitter balance, and potentially synchronizing group behavior, yawning plays a quiet but vital role in human physiology.

Understanding the science behind this reflex empowers us to respond wisely to fatigue rather than fight it blindly with stimulants or willpower alone. Instead of viewing yawning as a sign of weakness or rudeness, consider it valuable biofeedback—an internal check-in from your nervous system reminding you to pause, reset, and care for your cognitive health.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?