When someone passes away, their final wishes—often outlined in a will—must be carried out under the supervision of the legal system. This is where probate comes in. Despite being a common part of estate administration, many people don’t understand why a will must go through probate or what the process actually entails. Probate ensures that debts are paid, assets are distributed correctly, and the executor has legal authority to act on behalf of the estate. Understanding this process can help individuals plan more effectively and ease the burden on loved ones during an already difficult time.

What Is Probate and Why Is It Necessary?

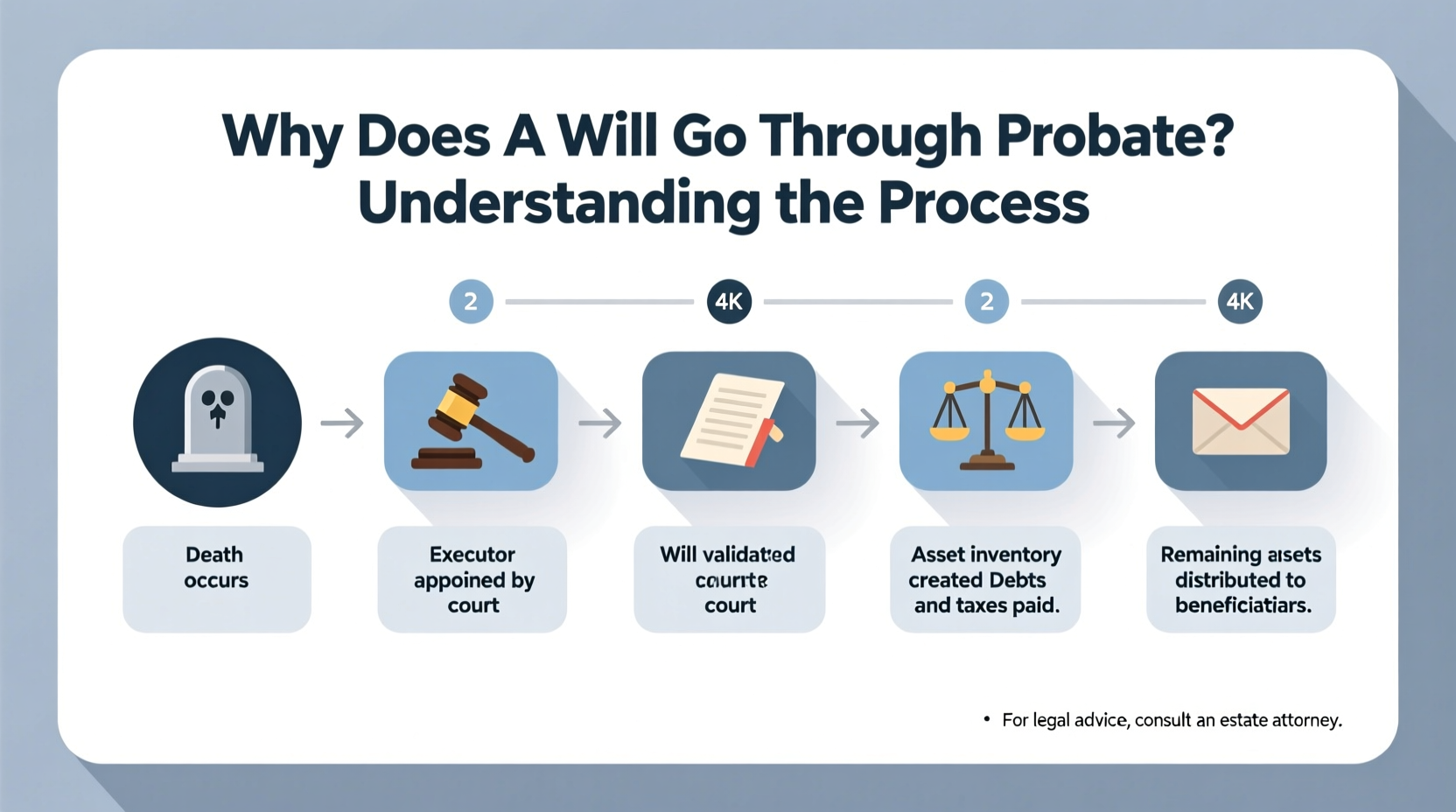

Probate is the court-supervised process of validating a deceased person’s will, identifying their assets, paying outstanding debts and taxes, and distributing the remaining property to beneficiaries. Even with a valid will, probate is typically required to give the executor legal standing to manage the estate. Without it, financial institutions and government agencies may refuse to release assets.

The primary reasons for probate include:

- Legal validation of the will: The court confirms that the document is authentic and reflects the decedent’s final wishes.

- Protection of creditors: Probate provides a formal window for creditors to file claims against the estate.

- Clear title transfer: Real estate, vehicles, and other titled assets often require probate to legally change ownership.

- Dispute resolution: If family members or beneficiaries contest the will, the court resolves conflicts under legal guidelines.

“Probate isn’t about creating bureaucracy—it’s about ensuring fairness, transparency, and legal integrity in the transfer of assets.” — Laura Simmons, Estate Law Attorney with 20+ years of experience

How the Probate Process Works: A Step-by-Step Guide

While probate procedures vary slightly by state, most follow a similar sequence. Here’s a general overview of the steps involved:

- Filing the Petition: The executor named in the will files a petition with the local probate court to begin the process. This includes submitting the original will.

- Notice to Heirs and Creditors: The court requires public notice (often via newspaper) so that potential creditors and interested parties can come forward.

- Appointment of Executor: The court formally appoints the executor, granting them “Letters Testamentary,” which authorize them to act on the estate’s behalf.

- Inventory and Appraisal: The executor identifies, locates, and values all probate assets. This may involve hiring appraisers for real estate, jewelry, or collectibles.

- Paying Debts and Taxes: Using estate funds, the executor pays valid creditor claims, funeral expenses, and any applicable estate or inheritance taxes.

- Distribution of Assets: After debts and taxes are settled, the remaining assets are distributed to beneficiaries as directed by the will.

- Closing the Estate: The executor files a final accounting with the court and requests formal closure of the estate.

Common Misconceptions About Probate

Many people assume that having a will avoids probate entirely. This is not true. A will must still be validated through probate unless assets are structured to bypass it (e.g., through trusts or joint ownership). Other misconceptions include:

| Misconception | Reality |

|---|---|

| A will avoids probate. | No—wills must be probated to be legally enforceable. Only non-probate assets (like life insurance or payable-on-death accounts) skip the process. |

| Probate always takes years. | Simple estates can close in 6–9 months. Complex cases may take longer, but delays are often due to disputes or incomplete documentation. |

| Probate is always expensive. | Costs vary by state and estate size. Many states cap executor and attorney fees at a percentage of the estate value (e.g., 2–4%). |

| Everything goes through probate. | Only assets solely in the decedent’s name require probate. Jointly owned property, trusts, and beneficiary-designated accounts avoid it. |

Real Example: The Johnson Family Estate

The Johnson family learned the importance of planning when Robert Johnson passed away unexpectedly at age 68. He had a will naming his wife, Susan, as executor and leaving half his estate to her and the rest to their two children. However, most of his assets—including his home, retirement accounts, and bank savings—were in his name only.

The probate process began immediately. Susan filed the will with the county court, published notices, and spent three months gathering account statements and property deeds. She discovered $45,000 in unpaid medical bills, which had to be settled before distributions. The house needed appraisal, and one son contested the division of a vintage car collection, delaying approval.

It took 11 months and approximately $8,000 in legal and court fees to close the estate. While the will was honored, the family realized too late that placing assets in a revocable trust could have avoided much of the delay and cost.

Strategies to Minimize or Avoid Probate

While probate serves important functions, it can be time-consuming and costly. Fortunately, several tools can reduce or eliminate the need for it:

- Revocable Living Trust: Transfers ownership of assets into a trust during life; upon death, the trustee distributes them without court involvement.

- Joint Ownership with Right of Survivorship: Real estate or bank accounts held jointly pass directly to the surviving owner.

- Payable-on-Death (POD) or Transfer-on-Death (TOD) Designations: Apply to bank accounts, stocks, and vehicles—assets transfer automatically upon death.

- Gifting During Life: Reducing estate size before death lowers probate complexity.

- Beneficiary Designations: Retirement accounts, life insurance, and annuities pass directly to named beneficiaries.

FAQ: Common Questions About Will Probate

Does every will have to go through probate?

Most do, especially if the decedent owned assets solely in their name. Small estates below a state-defined threshold (e.g., $50,000) may qualify for simplified procedures or exemption.

Can you speed up the probate process?

Yes. Having a clear, well-drafted will, organized records, and cooperative beneficiaries helps. Hiring an experienced probate attorney also prevents delays from procedural errors.

What happens if there's no will?

The estate goes through “intestate probate.” A court-appointed administrator follows state laws to distribute assets, usually to closest relatives. This often leads to outcomes that differ from what the person might have wanted.

Conclusion: Take Control of Your Legacy

Understanding why a will goes through probate empowers you to make informed decisions about estate planning. While the process ensures accountability and legal clarity, it also highlights the value of proactive strategies like trusts and beneficiary designations. By organizing your affairs now, you protect your loved ones from unnecessary stress, expense, and uncertainty later.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?