For millions of people around the world, cilantro—the vibrant green herb commonly used in salsas, curries, and salads—is a culinary delight. But for others, it’s an abomination that tastes unmistakably like bar soap. This sharp divide isn’t about pickiness or acquired taste; it’s rooted deep in our DNA. The reason some people perceive cilantro as soapy lies in a genetic variation that alters how we smell and taste certain chemical compounds. This article explores the science behind this phenomenon, explains the role of specific genes, and offers insights into how genetics influence food preferences on a broader scale.

The Soapy Flavor: A Genetic Sensitivity

The primary culprit behind the soapy taste of cilantro is a group of chemical compounds called aldehyde molecules. These are naturally occurring substances found in cilantro leaves, particularly long-chain aldehydes such as decanal and dodecanal. While these compounds contribute to cilantro’s fresh, citrusy aroma for most people, they also bear a striking chemical resemblance to ingredients found in some soaps and lotions—specifically those made with aldehyde-based fragrances.

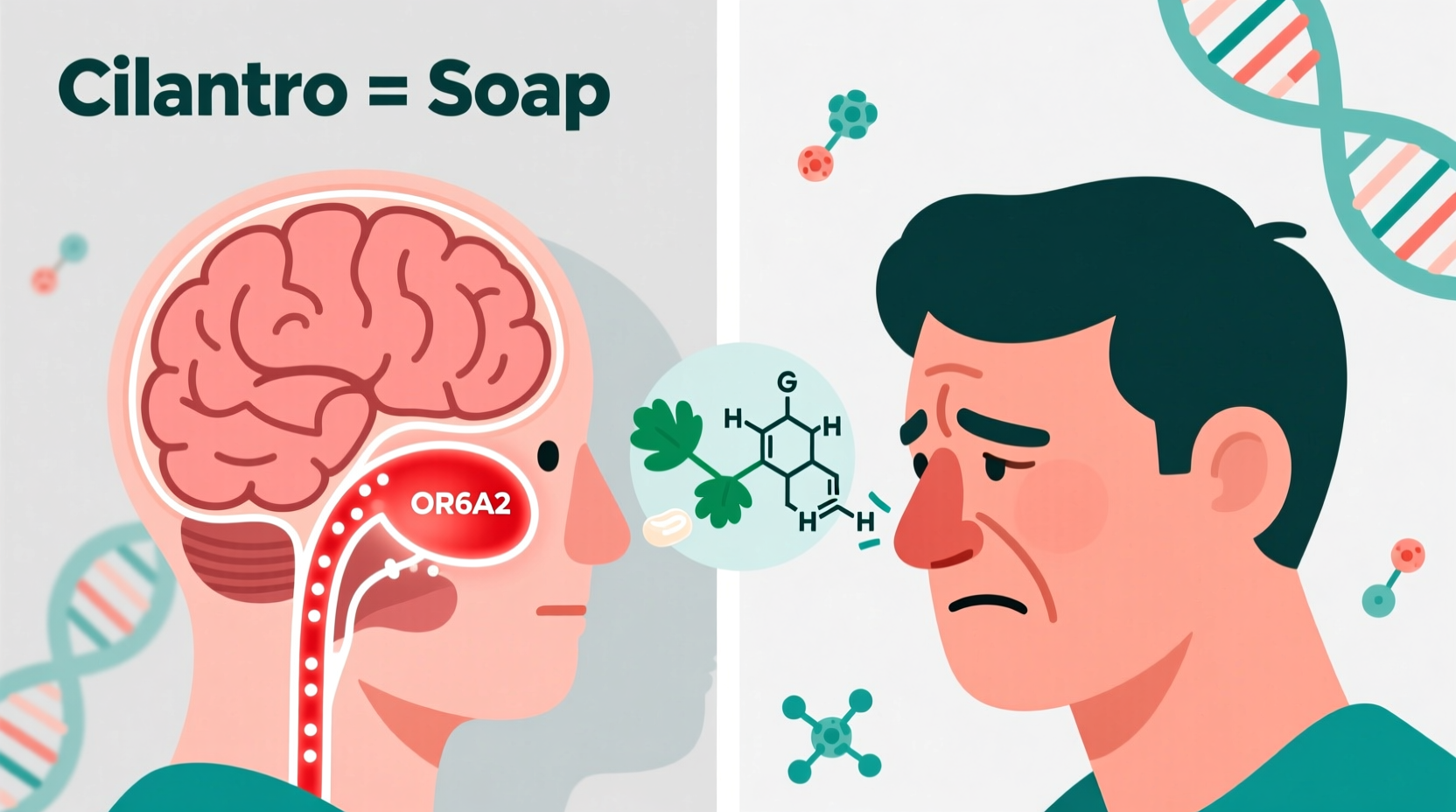

People who detect the soap-like flavor aren’t imagining it. Their olfactory receptors are actually detecting these aldehydes more intensely due to a genetic predisposition. The key lies in a cluster of olfactory receptor genes located on chromosome 11, specifically the OR6A2 gene. This gene encodes a receptor highly sensitive to aldehyde compounds. Individuals with certain variants of OR6A2 are far more likely to perceive the unpleasant, soapy note in cilantro.

“Genetic variation in olfactory receptors explains why cilantro can be a love-it-or-hate-it herb. It’s one of the clearest examples of how DNA directly influences sensory experience.” — Dr. Sarah Thompson, Molecular Geneticist at the University of California, San Diego

How Common Is the Cilantro-Soap Effect?

Studies suggest that between 4% and 14% of the global population perceives cilantro as soapy, though prevalence varies significantly by ancestry. Populations with higher frequencies of the sensitive OR6A2 variant include:

- East Asians (up to 21%)

- European populations (14–17%)

- Middle Eastern groups (moderate rates)

In contrast, only about 3–7% of people of African or Latin American descent report the soapy taste, despite heavy cilantro use in many Latin American cuisines. This suggests not only genetic but also cultural adaptation—repeated exposure may help individuals override initial aversions, even if their genetics make cilantro less appealing at first.

The Role of Olfaction in Taste Perception

It's important to understand that what we call “taste” is largely driven by smell. The tongue detects only five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. The complex flavors we associate with food—including the freshness of herbs, the richness of cheese, or the earthiness of mushrooms—come from olfactory signals processed through the nose.

When you chew cilantro, volatile aldehyde molecules travel up the back of your throat to the olfactory epithelium in your nasal cavity. Here, they bind to receptors like OR6A2. For those with the sensitive variant, this triggers a neural signal interpreted as “soapy” or “chemical,” which overrides the other pleasant herbal notes. This phenomenon is known as retronasal olfaction and is central to understanding why certain foods trigger strong reactions.

This also explains why some people can tolerate chopped cilantro in dishes but find whole leaves unbearable—the distribution and concentration of volatile compounds vary with preparation method.

Genetic Testing and Personalized Food Preferences

In recent years, direct-to-consumer genetic testing services like 23andMe and AncestryDNA have begun reporting on the cilantro-soap gene variant. Customers often discover they carry the OR6A2 sensitivity after receiving results, finally understanding a lifelong aversion.

While this insight doesn’t change the gene, it empowers individuals to make informed choices about food. More broadly, it highlights the emerging field of nutrigenomics—the study of how genes affect dietary response and preference. As research advances, we may see personalized nutrition plans that account not just for metabolism and allergies, but for sensory genetics as well.

| Population Group | % Likely to Taste Soap in Cilantro | Common Culinary Use of Cilantro |

|---|---|---|

| East Asian | 15–21% | Limited |

| European | 14–17% | Moderate |

| Latin American | 3–7% | High |

| African | 3–6% | Moderate to High |

| Middle Eastern | 8–12% | High |

Overcoming the Cilantro Aversion: Practical Strategies

Even if your genetics make cilantro unappealing, there are ways to reduce its off-putting qualities or substitute it entirely without sacrificing flavor.

Step-by-Step Guide to Managing Cilantro Sensitivity

- Blanch or cook cilantro briefly: Exposing the herb to heat degrades aldehyde compounds, mellowing the flavor and aroma.

- Use young leaves: Younger cilantro tends to have lower concentrations of volatile oils.

- Chop finely and mix thoroughly: Distributing small amounts evenly helps dilute the sensory impact.

- Pair with citrus or acid: Lemon or lime juice can balance out the bitterness and mask soapy notes.

- Try substitutes: Parsley, culantro (a related but stronger herb), or a blend of basil and mint may provide similar freshness without the aldehyde load.

Mini Case Study: Maria’s Journey with Cilantro

Maria, a 34-year-old graphic designer from Chicago, always avoided Mexican food because she couldn’t understand why everyone praised cilantro. To her, even a single leaf ruined an entire taco. After taking a DNA test, she learned she carried two copies of the sensitive OR6A2 variant—one from each parent—making her highly likely to perceive the soapy taste.

Armed with this knowledge, Maria experimented. She tried a recipe for roasted salsa where cilantro was blended after roasting tomatoes and onions. The heat had diminished the herb’s intensity, and when mixed with smoky peppers and lime, she barely noticed it. Over time, she began adding tiny amounts to guacamole and eventually developed a tolerance. While she still wouldn’t eat raw cilantro by the handful, she now enjoys it in cooked preparations—a testament to how understanding genetics can lead to practical culinary adjustments.

Checklist: How to Adapt If Cilantro Tastes Like Soap

- ✔ Get tested: Consider a genetic test to confirm if you carry the OR6A2 variant

- ✔ Cook it: Use heat to break down aldehyde compounds

- ✔ Substitute wisely: Try flat-leaf parsley or a mix of herbs for freshness

- ✔ Start small: Gradually introduce cilantro in strongly flavored dishes

- ✔ Pair with fat and acid: Combine with avocado, yogurt, or citrus to balance the taste

- ✔ Communicate: Let hosts or restaurants know if you’d prefer dishes without raw cilantro

Broader Implications: Genetics and Food Choice

The cilantro-soap phenomenon is just one example of how genetics shape eating behavior. Other well-documented cases include:

- Bitterness in Brussels sprouts: Linked to the TAS2R38 gene, which affects sensitivity to glucosinolates.

- Perception of sweetness: Variants in TAS1R2 influence how sugary foods taste.

- Alcohol flush reaction: Caused by ALDH2 gene mutations common in East Asian populations.

These variations underscore that food preferences are not purely cultural or habitual—they are biologically grounded. Recognizing this can foster greater empathy in social dining situations. Instead of dismissing someone’s dislike of cilantro as “picky eating,” we can acknowledge it as a legitimate sensory difference.

FAQ

Can you develop a taste for cilantro even if your genes make it taste like soap?

Yes, many people do. Repeated exposure, especially in cooked or blended forms, can help desensitize the palate over time. Cultural familiarity also plays a role—individuals raised with cilantro-heavy cuisines may learn to appreciate it despite initial aversion.

Is the soapy taste all in the nose?

Mostly, yes. The soapy perception comes primarily from smell, not taste. Retronasal olfaction—smell activated during chewing—delivers the aldehyde compounds to nasal receptors, where the genetic sensitivity is triggered.

Are there any health risks to disliking cilantro?

No. Disliking cilantro poses no health concerns. While cilantro has antioxidants and mild antimicrobial properties, it is not essential to a balanced diet. Plenty of other herbs and vegetables offer similar nutritional benefits.

Conclusion: Embracing Biological Diversity in Taste

The fact that cilantro tastes like soap to some people is a fascinating intersection of genetics, chemistry, and culture. It reminds us that flavor is not objective—it’s a personal experience shaped by our unique biology. Understanding the role of genes like OR6A2 not only demystifies individual food aversions but also enriches our appreciation for human diversity.

If you’ve always hated cilantro, you now know it’s not your fault—it’s your DNA. And if you love it, you might look at your next handful of chopped leaves with new gratitude for your genetic luck. Either way, this knowledge empowers smarter kitchen choices, better meal planning, and more inclusive dining experiences.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?