For millions of people, coffee is the morning ritual that jumpstarts the day. It’s expected to sharpen focus, elevate mood, and banish drowsiness. But what if, instead of feeling energized, you feel sluggish or even more tired after your cup? You’re not imagining it—and you’re far from alone. Many experience this counterintuitive reaction: caffeine, a stimulant, leads not to alertness but to fatigue. The answer lies in a complex interplay of biochemistry, timing, hydration, and individual physiology.

This phenomenon isn’t a flaw in your body—it’s a reflection of how deeply interconnected your nervous system, hormones, and metabolism are. Understanding why coffee can backfire helps you use caffeine more effectively and avoid the dreaded crash that leaves you reaching for another cup, only to repeat the cycle.

The Caffeine-Adenosine Tug-of-War

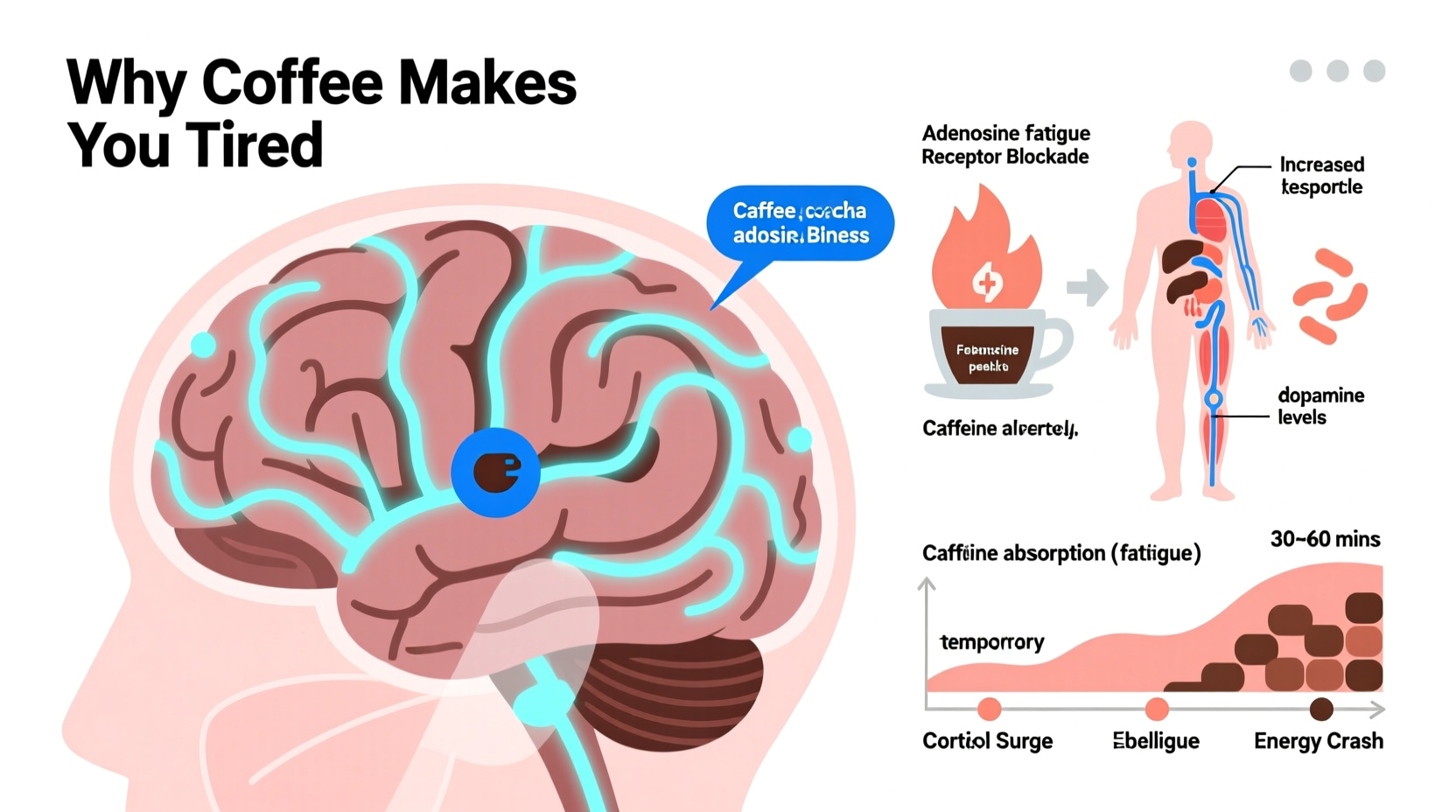

Caffeine works primarily by blocking adenosine receptors in the brain. Adenosine is a neurotransmitter that accumulates throughout the day as your cells consume energy. As adenosine levels rise, it binds to specific receptors, slowing neural activity and promoting feelings of sleepiness. This is your body’s natural way of signaling that it’s time to rest.

Caffeine mimics the shape of adenosine and binds to these same receptors—without activating them. By occupying the receptor sites, caffeine prevents adenosine from exerting its sedative effect. This blockade temporarily delays fatigue, creating a sense of alertness.

However, this effect is temporary. The adenosine doesn’t disappear; it continues to build up in the background. Once caffeine metabolizes and clears from your system—typically 3 to 5 hours later—the accumulated adenosine floods the receptors all at once. This sudden release often results in a pronounced “crash,” making you feel more tired than before you drank the coffee.

“Caffeine doesn’t eliminate fatigue—it masks it. When the mask comes off, your body reclaims what it was owed.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Neuropharmacologist, Johns Hopkins University

Hormonal Ripple Effects: Cortisol and the Stress Response

Your body operates on a circadian rhythm that regulates hormone production, including cortisol—the so-called “stress hormone” that also plays a key role in wakefulness. Cortisol naturally peaks in the early morning, helping you wake up and feel alert. Drinking coffee during this peak window (roughly 8–9 AM) may interfere with your body’s natural rhythm.

When you consume caffeine during high-cortisol periods, your adrenal glands may overproduce stress hormones. This can lead to a state of hyperarousal followed by exhaustion. Over time, repeated stimulation can desensitize your hormonal response, reducing both your natural energy spikes and your sensitivity to caffeine.

Additionally, elevated cortisol increases blood sugar and insulin levels. A rapid spike in insulin can cause a subsequent drop in glucose—your brain’s primary fuel. This hypoglycemic dip contributes to mental fog and fatigue, even if you’ve just had caffeine.

Optimal Coffee Timing Based on Circadian Rhythm

| Time of Day | Cortisol Level | Coffee Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 6–8 AM | Rising | Delay coffee 60–90 mins after waking |

| 9–11:30 AM | Peak | Avoid caffeine; rely on natural alertness |

| 12–2 PM | Dip | Ideal window for first coffee |

| 2–4 PM | Second rise | Suitable for moderate intake |

| After 5 PM | Falling | Avoid to prevent sleep disruption |

Dehydration and Its Fatigue-Inducing Impact

Coffee is a mild diuretic, meaning it increases urine production and can contribute to fluid loss. While moderate coffee consumption doesn’t cause significant dehydration, many people drink coffee without balancing it with sufficient water intake. Even mild dehydration—losing as little as 1–2% of your body’s water—can impair cognitive function, reduce concentration, and increase fatigue.

When dehydrated, your blood volume decreases slightly, reducing oxygen delivery to the brain and muscles. Your heart must work harder to pump blood, which can manifest as lethargy. Combine this with caffeine’s stimulating effect, and you create a false sense of alertness that quickly gives way to physical and mental exhaustion.

Individual Sensitivity and Genetic Factors

Not everyone processes caffeine the same way. Your genetic makeup plays a crucial role in how long caffeine stays in your system and how strongly it affects you. The CYP1A2 gene controls the enzyme responsible for breaking down caffeine in the liver. Some people are “fast metabolizers,” clearing caffeine within a few hours. Others are “slow metabolizers,” for whom caffeine lingers for 8 hours or more.

Slow metabolizers are more prone to jitteriness, anxiety, and disrupted sleep—even from morning coffee. They may also experience rebound fatigue as the prolonged presence of caffeine disrupts normal sleep architecture, leading to poorer quality rest. Over time, chronic poor sleep lowers baseline energy, making any perceived boost from coffee short-lived and ultimately counterproductive.

Another factor is tolerance. Regular coffee drinkers develop a physiological adaptation where their brain produces more adenosine receptors to compensate for caffeine’s blockade. This means they need more caffeine just to achieve the same level of alertness—a cycle that can exhaust the nervous system and contribute to chronic fatigue.

Mini Case Study: Sarah’s Afternoon Crash

Sarah, a 34-year-old project manager, starts her day with two strong coffees at 7:30 AM. By 10:30 AM, she feels anxious and scattered. At noon, she crashes hard—struggling to focus, yawning despite having just finished a latte. She blames her workload, but the real culprit is her caffeine pattern.

She’s consuming caffeine during her natural cortisol peak, amplifying stress hormones. The initial stimulation wears off by mid-morning, revealing built-up adenosine. Her second coffee provides a brief lift, but by 2 PM, she’s exhausted. She’s also drinking minimal water, compounding dehydration. After switching to one coffee at 9:30 AM and adding two glasses of water per cup, her energy stabilizes. Within a week, her afternoon crashes vanish.

How to Use Coffee Without the Crash: A Step-by-Step Guide

Using caffeine strategically can help you harness its benefits while avoiding fatigue. Follow this timeline-based approach to optimize your intake:

- Wait 60–90 minutes after waking before drinking coffee. Let your natural cortisol rise do its job first.

- Limits to 1–2 cups per day, ideally consumed before 2 PM to avoid sleep interference.

- Pair coffee with water. Drink a full glass of water before and after each cup.

- Avoid sugary additives. Sugar amplifies energy spikes and crashes. Opt for unsweetened or lightly sweetened options.

- Take caffeine breaks. Every 4–6 weeks, go caffeine-free for 3–5 days to reset receptor sensitivity.

- Monitor your sleep. If you’re not getting 7–8 hours of quality rest, caffeine will only mask deeper fatigue.

Checklist: Signs You’re Misusing Caffeine

- You need coffee to function, not to enhance performance

- You experience jitters, anxiety, or heart palpitations

- You crash within 2–3 hours of drinking coffee

- You rely on multiple cups to stay awake

- You have trouble falling or staying asleep

- You drink coffee past 3 PM regularly

FAQ: Common Questions About Coffee and Fatigue

Can decaf coffee still make me tired?

Decaf contains trace amounts of caffeine (about 2–5 mg per cup), which is unlikely to cause alertness or fatigue directly. However, if you associate coffee rituals with relaxation—such as sipping a warm beverage during a break—decaf can trigger a psychological wind-down response. Additionally, additives like sugar or creamers in decaf drinks may contribute to energy fluctuations.

Does the type of coffee affect how tired I feel?

Yes. Dark roasts contain slightly less caffeine than light roasts by volume, though the difference is minor. More impactful is how you prepare it: espresso has concentrated caffeine but is consumed in small volumes, while drip coffee delivers a steady dose over a larger serving. Cold brew tends to have higher caffeine content and smoother acidity, which some find less likely to cause jitters or crashes. Ultimately, brewing method, bean origin, and serving size all influence your body’s response.

Why do I feel sleepy immediately after drinking coffee?

Feeling sleepy right after coffee isn’t uncommon. One explanation is the adenosine rebound effect—if your brain is already saturated with adenosine due to sleep deprivation, caffeine’s blockade may provide only fleeting relief. Another possibility is a conditioned response: if you always drink coffee while sitting down or during a break, your body may associate the act with rest. Finally, the mild anxiety or increased heart rate from caffeine can trigger a parasympathetic “reset” response, causing drowsiness once the initial stimulation fades.

Conclusion: Reclaim Your Energy—Smarter Caffeine Use Starts Now

Coffee doesn’t have to leave you drained. Understanding the science behind why it sometimes makes you tired empowers you to use it as a tool—not a crutch. By aligning your caffeine intake with your body’s natural rhythms, staying hydrated, and respecting your genetic limits, you can enjoy sustained energy without the crash.

The goal isn’t to eliminate coffee, but to refine how you use it. Small changes—like delaying your first cup, drinking more water, or taking periodic tolerance breaks—can transform your relationship with caffeine. Instead of chasing alertness, you’ll cultivate lasting vitality.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?