Copper has a unique ability to melt ice significantly faster than most other metals—and even faster than ambient air or water under certain conditions. This phenomenon isn't magic; it's rooted in fundamental principles of physics and materials science. Understanding why copper outperforms other materials in this role reveals insights into thermal conductivity, heat transfer, and real-world applications from de-icing systems to advanced cooling technologies.

The Role of Thermal Conductivity

At the heart of copper’s ice-melting prowess is its extraordinary thermal conductivity. Among common metals, copper ranks near the top for its ability to transfer heat efficiently. With a thermal conductivity of approximately 401 watts per meter-kelvin (W/m·K) at room temperature, copper conducts heat about 30 times better than stainless steel and over 800 times better than air.

When a piece of copper comes into contact with ice, it doesn’t generate heat on its own. Instead, it acts as a rapid conduit for ambient thermal energy—drawing warmth from the surrounding environment (like your hand, a countertop, or the air) and delivering it directly to the point of contact with the ice. This efficient transfer means that heat accumulates quickly at the interface, accelerating the phase change from solid to liquid.

How Heat Transfer Works on Contact

Melting ice requires energy—specifically, the latent heat of fusion, which for water is about 334 joules per gram. This energy must be supplied externally to break the hydrogen bonds holding water molecules in a rigid crystalline structure.

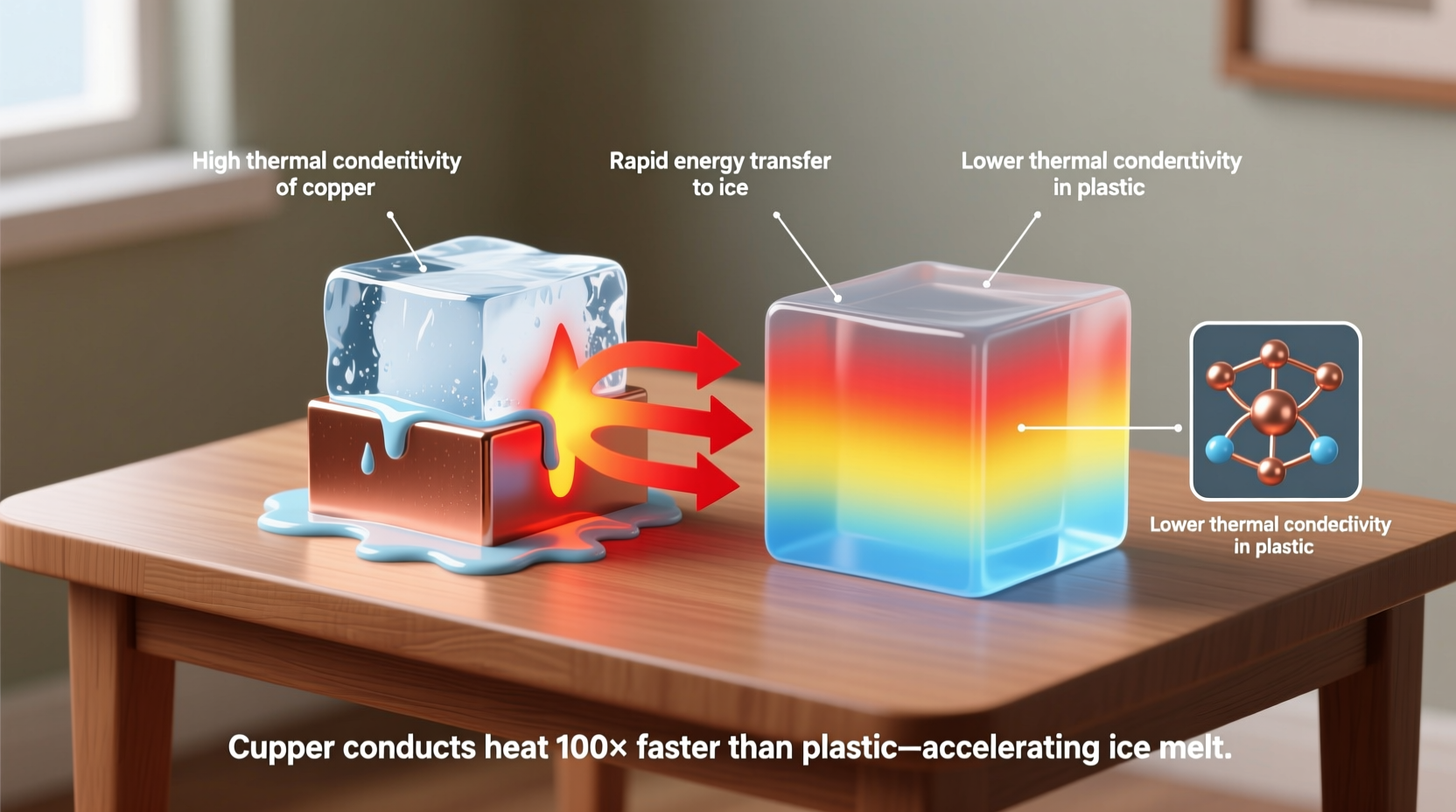

Materials vary widely in how quickly they can deliver this energy. A plastic rod, for example, insulates rather than conducts, so very little heat reaches the ice. Wood performs similarly. But copper functions like a thermal superhighway. The moment it touches ice, it begins shuttling thermal energy from warmer areas to the cold surface, enabling continuous melting.

In practical demonstrations, placing identical ice cubes on copper, aluminum, steel, and plastic surfaces shows dramatic differences. The ice on copper often melts completely within minutes, while others remain largely intact. This isn’t due to copper being inherently “hotter,” but because it maximizes the rate of heat delivery.

“Copper’s unmatched thermal conductivity allows it to serve as one of the most effective passive heat exchangers available. It turns ambient warmth into actionable melting power.” — Dr. Alan Zhou, Materials Scientist, MIT

Comparison of Common Materials in Ice Melting

| Material | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) | Relative Melting Speed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | 401 | Very Fast | Highest among common metals; ideal for rapid heat transfer |

| Aluminum | 237 | Fast | Lighter and cheaper, but less conductive than copper |

| Steel (Stainless) | 15–20 | Slow | Poor conductor compared to copper; minimal melting effect |

| Iron | 80 | Moderate | Better than steel but far below copper |

| Plastic | 0.1–0.5 | Negligible | Acts as an insulator; slows heat transfer |

| Wood | 0.04–0.4 | None | Traps heat; no meaningful melting occurs |

Real-World Example: The Copper Door Handle Phenomenon

In colder climates, building managers have observed that ice accumulates less on door handles made of copper compared to those made of stainless steel or brass—even when both are exposed to identical conditions. During winter storms, snow-laden hands touching copper handles leave behind wet marks, but rarely form icy coatings. Meanwhile, steel handles often become encased in a layer of frost or frozen moisture.

This difference was studied in a small-scale field test at a community center in Vermont. Two identical exterior doors were fitted—one with a copper handle, the other with stainless steel. Over five consecutive snowy days, the copper handle remained largely ice-free, while the steel version required daily scraping. Researchers concluded that body heat transferred through brief human contact was sufficient to initiate melting on copper, and the metal retained and redistributed that heat more effectively.

Step-by-Step: How Copper Melts Ice in Three Stages

- Contact Initiation: Copper touches the ice surface. Even slight temperature differences trigger heat flow from the warmer material (copper) to the colder one (ice).

- Heat Redistribution: Ambient heat from the surroundings continuously flows into the copper, which then channels it to the contact zone. Unlike poor conductors, copper doesn’t lose heat across its volume—it directs it precisely where needed.

- Phase Transition: As energy builds at the interface, the ice absorbs the latent heat of fusion and begins to melt. Liquid water forms and may drain away, exposing new ice to continue the cycle until equilibrium is reached or the ice is gone.

Practical Applications Beyond Curiosity

The principle behind copper’s ice-melting capability is leveraged in several engineering and safety contexts:

- Anti-icing surfaces: Copper-coated railings or handrails in freezing environments reduce slip hazards by preventing ice buildup.

- Cooling systems: Copper tubing in refrigeration units ensures rapid heat exchange, improving efficiency.

- Emergency tools: Some survival kits include copper strips for melting small amounts of drinking water from snow when fire isn't an option.

- Architecture: Buildings in cold regions sometimes use copper flashing or roofing elements that naturally shed ice due to thermal activity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does copper generate heat on its own?

No, copper does not produce heat. It simply transfers existing thermal energy very efficiently. Any warmth comes from the environment—your hand, sunlight, or ambient air.

Can other metals melt ice fast too?

Yes, but to a lesser extent. Aluminum is the closest common alternative, though it only conducts about 60% as well as copper. Silver technically has higher conductivity (~429 W/m·K), but its cost and softness limit practical use.

Will copper stop working in extremely cold environments?

Not exactly. Copper will still transfer heat, but if the ambient temperature is far below freezing and no external heat source is present, there won’t be enough thermal energy to drive melting. Its effectiveness depends on a temperature gradient.

Actionable Checklist: Using Copper to Manage Ice

- Identify high-risk areas prone to icing (e.g., steps, railings, locks).

- Consider installing copper tape, strips, or fixtures in these zones.

- Use copper tools (like rods or plates) to manually melt stubborn ice spots.

- Avoid painting over copper surfaces—coatings reduce thermal contact.

- Combine with passive solar exposure: position copper elements where they receive sunlight for enhanced performance.

Conclusion: Harnessing Nature’s Best Conductor

The reason copper melts ice faster lies in its unparalleled ability to move heat. It doesn’t rely on electricity, moving parts, or chemical reactions—just the laws of thermodynamics executed with remarkable efficiency. Whether you're troubleshooting a frozen lock or designing a safer walkway, understanding this principle empowers smarter, sustainable solutions.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?