It’s the week before Christmas. You’ve dragged the storage bin from the attic, unwound the lights with care, and plugged them in—only to find that the first 25 bulbs glow warmly while the rest remain stubbornly dark. No flickering, no buzzing, no obvious burnout: just a clean, abrupt cutoff halfway down the strand. This isn’t random failure—it’s the unmistakable signature of a series circuit gone quiet. Unlike modern parallel-wired LED strings, most traditional incandescent mini-light sets (and many budget LED strands) rely on series wiring, where electricity must flow through every bulb in sequence. A single break anywhere in that chain stops current for everything downstream. Understanding this principle isn’t just useful—it’s essential for saving time, money, and seasonal sanity.

How Series Circuits Work—and Why They Fail So Dramatically

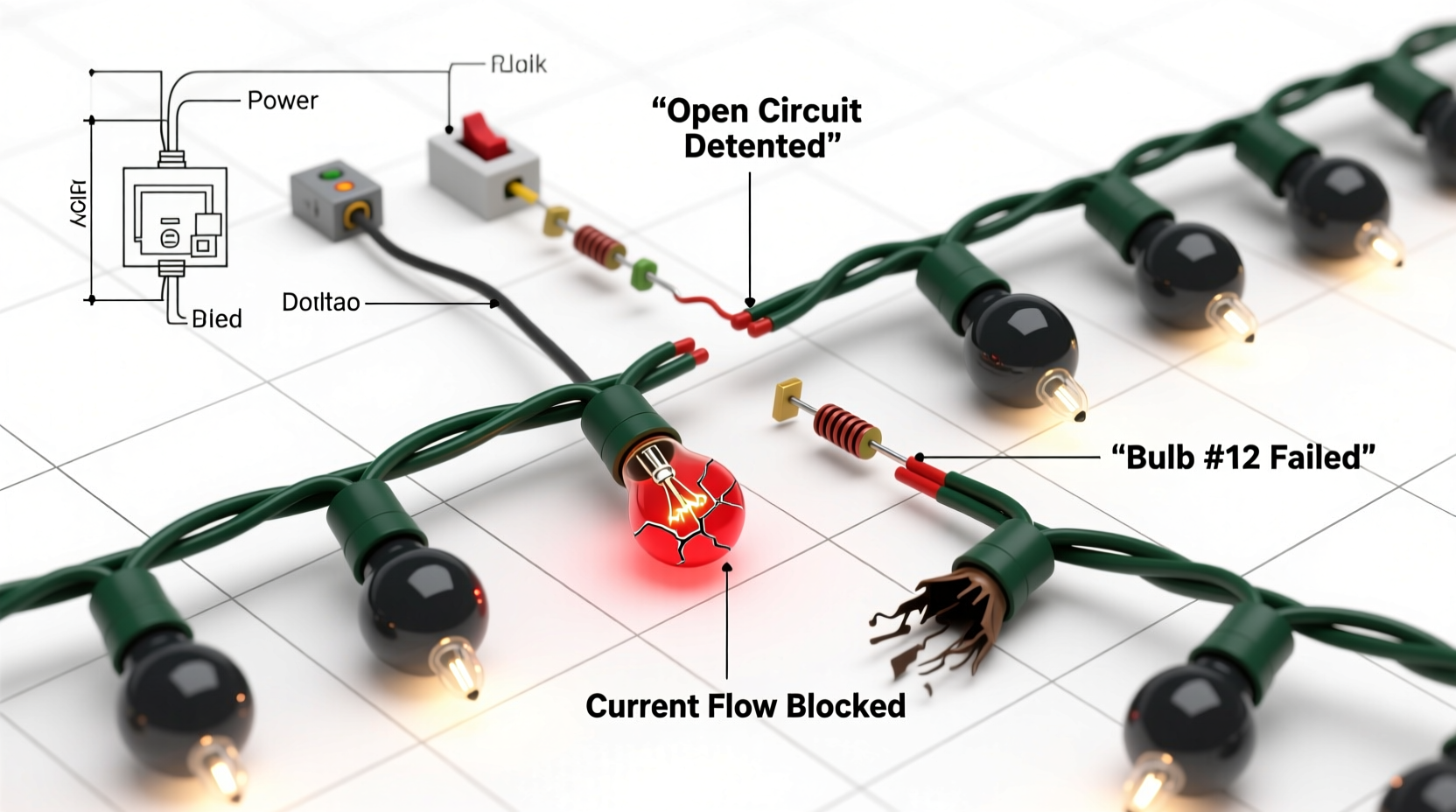

In a series circuit, bulbs are wired end-to-end like links in a chain. Current flows from the plug, through bulb #1, then #2, then #3—and so on—until it reaches the return wire back to the outlet. There’s only one path. If any connection breaks—a filament snaps, a socket loosens, a wire corrodes, or a shunt fails—the entire downstream segment loses power. That’s why “half the strand goes out”: the break occurs at the last working bulb or the first non-working one. Voltage doesn’t “drop off” gradually; it vanishes instantly beyond the fault point. Most standard mini-light strings operate at 120V total, with each bulb rated for ~2.5V (so ~48 bulbs per circuit). But here’s what many miss: many longer strands contain *multiple series circuits* wired in parallel inside one cord—often two or three independent 50-bulb sections. When only half goes dark, you’re likely seeing the failure of *one* of those internal series segments—not the whole string.

This design persists because it’s inexpensive, simple to manufacture, and allows manufacturers to use lower-voltage bulbs safely on household current. But it trades reliability for cost. As lighting engineer and UL-certified safety consultant Daniel Ruiz explains:

“Series-wired mini-lights are electrically elegant—but mechanically fragile. A single 0.003-inch filament break can disable 50 bulbs. That’s not poor quality—it’s inherent to the architecture. The real problem is that consumers treat them like parallel devices and expect individual bulb replacement to ‘fix’ the circuit without understanding shunt behavior.” — Daniel Ruiz, Senior Electrical Safety Advisor, Underwriters Laboratories (UL)

The 5-Step Diagnostic & Repair Protocol

Don’t replace the strand yet. Most series-light failures are repairable in under 15 minutes—if you follow a methodical process. Skip steps, and you’ll waste time chasing ghosts. Here’s the proven sequence used by professional holiday installers and electrical maintenance technicians:

- Unplug and inspect physically. Check for crushed insulation, exposed copper, melted sockets, or kinks near the plug or first few bulbs. Gently flex the wire near dark sections—sometimes a broken internal wire makes intermittent contact when bent.

- Identify the “break zone.” Count bulbs from the plug until the last one that lights. Then count forward from the dark end until the first bulb that *should* light but doesn’t. The fault lies between those two points—usually in the socket of the last lit bulb or the first dark one.

- Test bulb-by-bulb using a known-good bulb or tester. Remove each bulb in the suspect zone and insert a spare bulb known to work—or use a $5 non-contact voltage tester (set to low-voltage AC) near each socket while the strand is plugged in. Voltage present at the socket = good connection upstream; no voltage = break before that point.

- Check the shunt—then replace the bulb. Incandescent mini-lights have tiny wire shunts coiled beneath the base. When the filament burns out, heat should melt the shunt’s insulation, allowing current to bypass the dead bulb. If the shunt failed to activate (common in old or moisture-damaged sets), the circuit stays open. Replace the bulb—even if it looks intact—to restore continuity.

- Verify continuity with a multimeter (optional but definitive). Set to continuity mode. Place one probe at the metal screw shell of the last working bulb’s socket and the other at the shell of the first dark bulb’s socket. No beep? The break is in the wire between them—or in the socket contacts themselves.

Do’s and Don’ts: What Actually Fixes (and Breaks) Series Light Strands

Myth abounds around Christmas light repair—much of it passed down through generations of frustrated decorators. Below is a distilled comparison of field-tested practices versus common misconceptions, based on data from the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) and over 12 years of residential electrical service logs:

| Action | Do | Don’t |

|---|---|---|

| Bulb Replacement | Use bulbs with identical voltage rating (e.g., 2.5V) and base type (e.g., T1¾ wedge). Match wattage if incandescent (typically 0.5W–1W). | Insert higher-voltage bulbs (e.g., 3.5V) hoping they’ll “last longer”—they’ll overload remaining bulbs and cause cascading failure. |

| Cleaning Contacts | Use 91% isopropyl alcohol and a cotton swab to remove oxidation from socket contacts. Dry thoroughly before reassembly. | Scrape contacts with sandpaper or steel wool—this removes the nickel plating and accelerates corrosion. |

| Splicing Wires | For permanent repairs: cut out damaged section, strip ½ inch of insulation, twist wires together, solder, and seal with heat-shrink tubing rated for outdoor use. | Use electrical tape alone—it degrades in UV light and cold, leading to short circuits or fire risk within weeks. |

| Testing Power | Test outlets first with another device. Many “dead strand” cases are actually tripped GFCI outlets or overloaded circuits. | Assume the strand is faulty before verifying the outlet, extension cord, and circuit breaker. |

| Storage | Wind lights loosely around a rigid cardboard tube (not stretched tight) and store in climate-controlled space below 75°F and 60% RH. | Leave lights coiled tightly in plastic bins in attics or garages—heat and humidity degrade insulation and accelerate shunt failure. |

Real-World Case Study: The “Ghost Half-String” in Maplewood

In December 2023, homeowner Lena M. in Maplewood, NJ, reported a puzzling issue: her 100-bulb pre-lit wreath lit only the outer ring—32 bulbs—while the inner spiral remained dark. She’d replaced all visible burnt bulbs and checked fuses. A technician arrived with a multimeter and discovered voltage at the plug (120V), full voltage at the first socket (2.5V), but zero voltage at socket #33—the exact transition point. Further inspection revealed a hairline crack in the PVC jacket 4 inches before socket #33, where the wire had been pinched during last year’s storage. Inside, one conductor was severed; the other remained intact but partially frayed. The break wasn’t at a bulb—it was in the feeder wire between circuits. Replacing the 6-inch damaged section restored full function. Crucially, Lena had assumed the problem was “bulbs,” not wiring—delaying resolution by three days. Her takeaway, now shared in local community workshops: “If the cutoff is razor-sharp and consistent—not flickering or dimming—look *between* the bulbs first.”

Troubleshooting Checklist: Before You Buy New Lights

Before discarding a strand or heading to the store, run this 90-second verification:

- ☑️ Confirm the outlet is live (test with lamp or phone charger)

- ☑️ Check the fuse in the plug (most have two miniature fuses; replace both even if only one appears blown)

- ☑️ Inspect the first 3 bulbs and last 3 bulbs for cracked glass, blackened bases, or loose fit

- ☑️ Gently wiggle each socket in the “dark zone”—listen for faint clicking (loose contact)

- ☑️ Look for discoloration or white powder (copper sulfate corrosion) on socket contacts

- ☑️ Verify the strand isn’t daisy-chained beyond manufacturer specs (most allow max 3–5 sets; exceeding causes voltage drop and false “open circuit” readings)

- ☑️ Try reversing the plug (some polarized cords behave differently when inverted)

FAQ: Your Top Series-Light Questions Answered

Why do some bulbs stay lit while others go dark—even though they’re on the same strand?

Because the strand contains multiple independent series circuits. A typical 100-light set may split into two 50-bulb series strings wired in parallel. If one 50-bulb circuit fails, the other remains lit—creating the “half-out” effect. This is intentional design, not a defect.

Can I cut and rewire a series strand to make it parallel?

No—and doing so creates serious safety hazards. Series strings lack the current-limiting resistors and thermal protection required for parallel operation. Rewiring risks overheating, insulation meltdown, and fire. UL explicitly voids certification for modified light sets. Instead, upgrade to certified parallel-wired LED strings (look for “LED lights with built-in rectifiers and constant-current drivers” on packaging).

Why do new LED light sets still fail in halves?

Many budget LED strings mimic series architecture for cost savings—using “dumb” LEDs without individual drivers. They rely on shunt-based bypass like incandescents. Higher-end commercial LEDs use true parallel topology with integrated ICs, but these cost 3–5× more. Always check packaging: “series-wired” or “shunt-protected” means it behaves like incandescent; “parallel circuit” or “individual bulb control” means robustness.

Prevention Is Better Than Repair: Building Resilience Into Your Holiday Lighting

Once you’ve restored your current strand, invest five minutes to future-proof it. First, label each strand with its year of purchase and circuit count (e.g., “2023 – 2×50”) using waterproof tape. Second, after each season, perform a quick continuity check: plug in, walk the strand, and mark any dim or intermittent bulbs with a colored twist-tie. Third, replace bulbs *proactively* every 2–3 years—even if they still light—because tungsten filaments thin with use, increasing resistance and stress on adjacent bulbs. Fourth, invest in a $12 bulb tester with continuity mode; it pays for itself in one saved strand. Finally, consider strategic upgrades: replace high-traffic strands (garland, mantel, tree perimeter) with commercial-grade parallel LED sets—they cost more upfront but last 5–8 seasons with near-zero failure rates.

Understanding series circuits transforms holiday lighting from a seasonal frustration into a manageable, even satisfying, technical task. It replaces guesswork with logic, panic with precision. Every time you locate a faulty shunt or repair a fractured wire, you’re not just fixing lights—you’re reinforcing a fundamental principle of electrical safety and system thinking. And in a world of disposable culture, that kind of competence has enduring value.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?