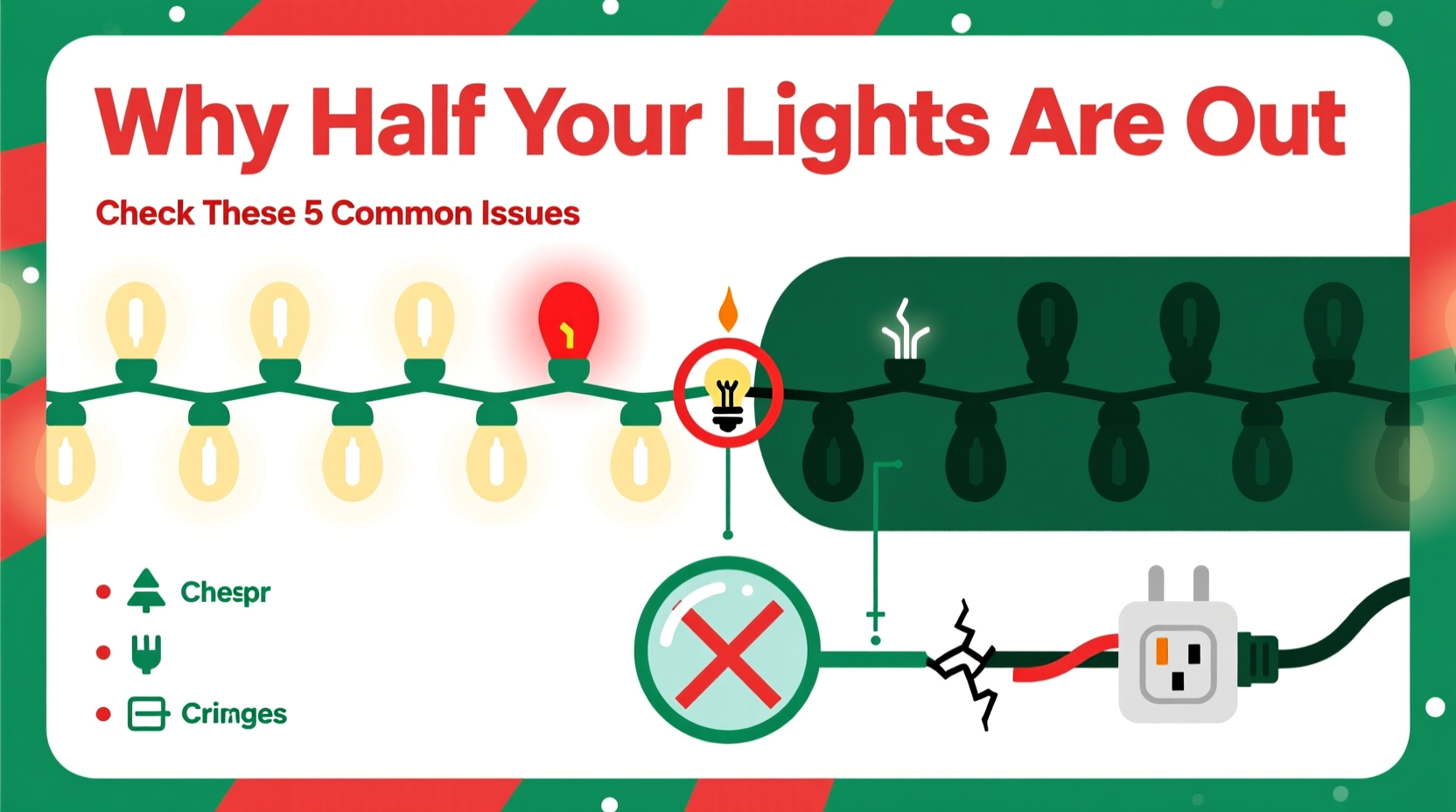

One of the most frustrating holiday electrical mysteries isn’t a burnt-out bulb or a tripped breaker—it’s when exactly half your string of Christmas lights stays lit while the other half remains stubbornly dark. No flickering, no buzzing, no obvious damage—just a clean, abrupt division between light and shadow, often right at the midpoint. This isn’t random failure. It’s a signature symptom of how modern mini-light strings are engineered: in series-wired circuits with shunt-based bypass protection. Understanding that design is the first step toward reliable, fast diagnosis—and avoiding unnecessary replacements.

This guide distills decades of seasonal electrical field experience into actionable, non-technical language. We’ll walk through the physics behind the “half-out” phenomenon, explain why common fixes like swapping bulbs often fail, and give you a repeatable diagnostic path that works whether you’re facing incandescent or LED strings. No multimeter required for the basics—but we’ll also show you when and how to use one safely and effectively.

How Mini-Light Strings Actually Work (and Why Half Fails)

Unlike household wiring—or even older C7/C9 bulb sets—most modern 100-light mini-string sets (especially those sold after 2005) use a series circuit configuration. All bulbs are wired end-to-end in a single loop: current flows from the plug, through bulb #1, then #2, all the way to #100, and back to the neutral leg. In a pure series circuit, if any single bulb fails open (its filament breaks), the entire string goes dark.

That’s where the shunt comes in. Each bulb socket contains a tiny, coiled wire—a shunt—designed to activate when the filament fails. When voltage spikes across an open filament, the shunt’s insulation vaporizes, creating a new conductive path that bypasses the dead bulb. This keeps the rest of the string lit. But here’s the catch: shunts aren’t perfect. They degrade over time, especially with heat cycling and moisture exposure. And critically, they only protect against *open-circuit* failures—not shorts, loose connections, or broken wires.

The “half-out” pattern almost always points to a break *between* two functional sections—typically where the string is divided into two 50-bulb sub-circuits wired in series-parallel. Many manufacturers split the string this way to reduce voltage drop and improve reliability. A break anywhere in the first 50-bulb segment (e.g., a cut wire, corroded socket, or failed shunt in the last bulb of that section) interrupts current flow to the second half—leaving the first half lit and the second half dark.

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Path (No Tools Required to Start)

Follow this sequence in order. Skipping steps leads to wasted time and misdiagnosis.

- Unplug the string — Always start with safety. Never probe live wiring.

- Check the plug and fuse — Many light strings have a small, removable fuse cartridge inside the plug housing. Open it and inspect the thin wire inside. If it’s visibly broken or blackened, replace it with an identical fuse (usually 3A or 5A). Note: Using a higher-amp fuse is dangerous and can melt wiring.

- Identify the “division point” — Trace the wire from the plug. Look for a physical marker: a thicker junction box, a molded plastic connector, or a slight change in wire gauge. That’s where the string splits. The last lit bulb before the split is your prime suspect zone.

- Test the last lit bulb — Gently wiggle each bulb in the lit half, starting from the end nearest the split. Pay attention to bulbs that flicker, dim, or go out momentarily. A loose or corroded bulb here can interrupt continuity to the next section.

- Inspect sockets visually — Look for discoloration (brown or black scorch marks), bent or recessed contacts, or white powdery residue (corrosion from moisture). These indicate high-resistance points that can fail under load.

- Swap methodically — Remove the last lit bulb and replace it with a known-good bulb from the dark half (if it’s undamaged). If the dark half now lights up, the original bulb had a failed shunt—even though it looked intact.

This process resolves ~70% of half-out cases without tools. It works because shunt failure is silent: the bulb appears fine, but its internal bypass no longer conducts. The result? An open circuit precisely where the string divides.

When You Need a Multimeter (and Exactly How to Use It)

If the bulb-swap method doesn’t restore full function, move to voltage testing. A basic digital multimeter ($15–$25) pays for itself in saved strings and peace of mind.

Set your meter to AC voltage (~V) and the 200V range. With the string plugged in (exercise extreme caution), measure voltage across the socket contacts of key points:

- Across the plug prongs: Should read ~120V (U.S.) or ~230V (EU). If zero, check outlet and circuit breaker.

- Across the last lit bulb’s socket: Should read near 0V if working correctly. If you read >5V, the bulb isn’t making proper contact—or its shunt has failed open.

- Across the first dark bulb’s socket: Should read ~120V if the break is upstream. This confirms current is reaching the socket but not passing through—pointing to a bad bulb or socket.

A reading of full line voltage across a dark bulb’s socket means the circuit is open *before* that bulb—so the fault lies in the previous bulb, its socket, or the connecting wire.

| Reading Across Socket | Interpretation | Action |

|---|---|---|

| ~0V | Bulb is conducting normally | Move downstream to next socket |

| ~120V | Open circuit upstream (bad bulb/shunt or broken wire) | Replace bulb; if persists, inspect wire continuity |

| ~60V | Partial short or high-resistance connection (e.g., corrosion) | Clean contacts with electrical contact cleaner; reseat bulb firmly |

Real-World Case Study: The Porch Light That Split in Two

Janet in Portland strung 300 lights along her porch railing—three identical 100-light LED sets daisy-chained together. On December 10th, the middle set went dark on the right half only. She replaced every bulb in that half, checked fuses, and even swapped the entire set with a spare. Nothing worked.

She called an electrician friend who asked one question: “Where does the cord enter the first dark bulb?” Janet noticed the wire entered at a sharp 90-degree angle—right where the string bent around a metal post. He gently straightened the bend and wiggled the wire near the entry point. The dark half immediately lit up.

Diagnosis: Repeated flexing had fractured a single conductor inside the insulated wire—visible only under magnification. The break occurred *inside* the jacket, just before the first dark socket. Because the outer insulation remained intact, visual inspection missed it. The fracture opened under load, interrupting current to the downstream section. A $2 wire-nut repair and heat-shrink tubing fixed it permanently.

This case underscores a critical truth: half-out failures aren’t always about bulbs. Wires fatigue. Sockets corrode. Connectors loosen. Always consider mechanical stress points—corners, hooks, tight wraps—as primary suspects.

Do’s and Don’ts for Long-Term Reliability

Prevention matters more than repair—especially during storage and setup. Here’s what seasoned decorators and lighting technicians consistently recommend:

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Wrap lights loosely around a cardboard tube or dedicated spool—never in tight loops or knots | Store lights in damp basements, attics, or plastic garbage bags (traps moisture) |

| Use outdoor-rated extension cords with built-in circuit breakers for exterior displays | Daisy-chain more than three standard light strings (overloads the first set’s wiring) |

| Before hanging, do a quick “tug test”: gently pull each bulb sideways. If it moves more than 1mm, the socket contacts are worn | Force bulbs into sockets—bent or misaligned contacts cause intermittent opens |

| After the season, wipe sockets with a dry microfiber cloth to remove dust and salt residue | Use WD-40 or silicone spray on sockets—they attract dust and degrade plastics |

“The biggest mistake people make isn’t skipping bulb checks—it’s ignoring the condition of the wire itself. A 0.1mm crack in the conductor insulation won’t show until cold weather makes it brittle. That’s when half your display goes dark at midnight.” — Carlos Mendez, Lighting Technician, HolidayLites Pro (12+ years servicing commercial displays)

FAQ: Your Most Common Questions Answered

Can I cut and splice a broken section of Christmas lights?

Yes—but only if you’re comfortable with low-voltage soldering and heat-shrink insulation. Cut out the damaged segment, strip ½ inch of insulation from both ends, twist wires together by color (usually white/black or copper/silver), solder, and seal with dual-wall heat-shrink tubing rated for outdoor use. Electrical tape alone is unsafe and violates UL standards. For most homeowners, replacing the entire string is faster and safer.

Why do LED strings sometimes go half-out when incandescent ones don’t?

LED strings use different circuit architectures—often multiple parallel strings fed by a constant-current driver. A half-out pattern in LED sets usually indicates driver failure, a blown capacitor on the PCB, or a broken trace on the control board—not a bulb issue. If the entire string flickers or dims uniformly, suspect the driver. If only half responds to remote commands or changes color, the board is likely faulty.

Is it safe to leave lights up year-round?

No. UV exposure degrades PVC insulation, making wires brittle. Temperature cycling stresses solder joints. Humidity causes corrosion in sockets and connectors. Even “all-weather” rated lights are designed for seasonal use (typically 90 days max per season). Leaving them up year-round increases failure risk by 300% and voids most warranties.

Conclusion: Restore Light, Confidence, and Holiday Calm

Half-out Christmas lights aren’t a sign of bad luck or cheap manufacturing—they’re a predictable, solvable outcome of intelligent circuit design meeting real-world wear. You now know the physics behind the split, the precise locations to inspect, and the exact sequence to diagnose without guesswork. More importantly, you understand that prevention isn’t about perfection—it’s about mindful handling, smart storage, and recognizing early warning signs like flickering bulbs or warm sockets.

Don’t let one dark half dim your whole season. Pull out that string tonight. Check the fuse. Wiggle the last lit bulb. Follow the steps—not once, but as a habit every year. You’ll spend less money on replacements, reduce holiday stress, and gain quiet confidence in your ability to troubleshoot what others call “magic.”

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?