It’s a holiday-season ritual: you hang your lights, plug them in—and only the first 25 bulbs glow while the rest sit dark. Or worse: the first section shines brightly, then everything beyond a certain point flickers weakly or dies completely. You check the fuse, jiggle the plugs, replace a bulb, and still—half the string stays stubbornly off. This isn’t random failure. It’s physics made visible. Understanding whether your lights are wired in series or parallel isn’t just technical trivia—it’s the key to diagnosing, fixing, and preventing this exact frustration. And it matters more than ever as LED strings grow more complex, with hybrid wiring schemes, built-in rectifiers, and shunt-based fault tolerance that behave very differently from classic incandescent setups.

How Series Wiring Causes “Half-Out” Failures

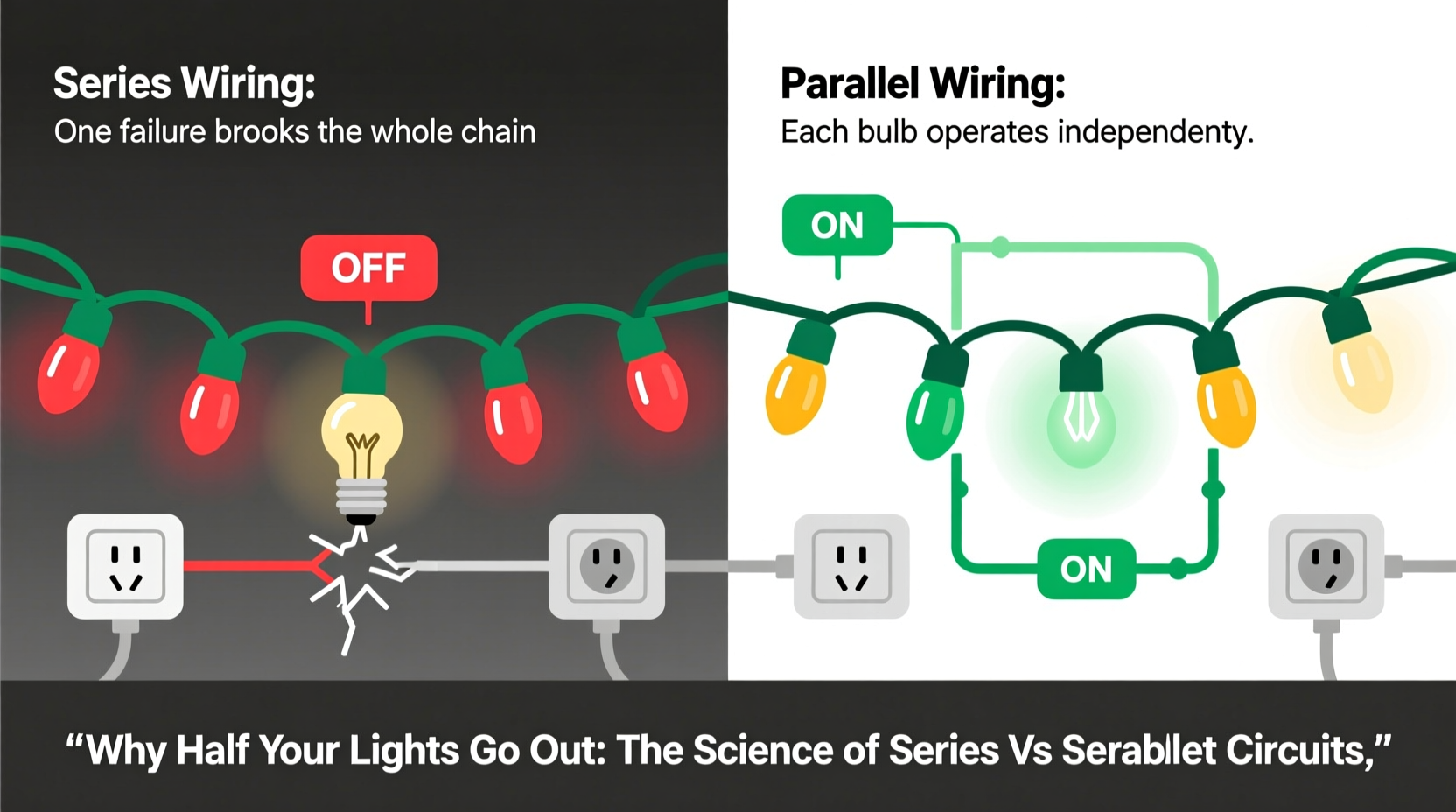

In a purely series-wired string, electricity flows through each bulb in a single path—like beads on a thread. The full line voltage (typically 120V in North America) is divided across all bulbs. For example, a 50-bulb incandescent string might assign 2.4 volts per bulb (120V ÷ 50). If one bulb burns out, its filament breaks, opening the circuit. No current can flow anywhere beyond that break—so every bulb downstream goes dark. That’s why a single dead bulb can kill an entire section.

But here’s where it gets subtle: many older incandescent strings used “shunted” sockets. When a bulb unscrews or burns out, a tiny metal bridge inside the socket closes automatically, bypassing the dead bulb and keeping the circuit intact. That’s why some vintage strings stayed lit despite missing bulbs—until the shunt failed or corrosion built up. Modern LED strings rarely use mechanical shunts. Instead, they rely on electronic shunts—tiny semiconductor devices embedded in each bulb’s base. These activate only when voltage across the LED exceeds a threshold (e.g., when the adjacent LED fails), rerouting current around the open component.

Yet even with shunts, series strings remain vulnerable to partial failure. A weak shunt, degraded solder joint, or cracked PCB trace can create high resistance—not a full open circuit, but enough to drop voltage significantly downstream. That’s why you’ll often see the first third of the string bright, the middle third dim, and the last third completely dark: voltage sag compounds with each compromised connection.

Why Parallel Wiring Usually Prevents Partial Failure

In a true parallel configuration, each bulb connects directly across the full supply voltage. Think of it like individual branches feeding off a main trunk—cut one branch, and the others stay green. If one bulb fails open in a parallel string, current simply routes around it through the remaining paths. All other bulbs maintain full brightness. This is why commercial-grade landscape lighting and most indoor architectural LED strips use parallel or constant-voltage wiring (e.g., 12V or 24V DC with individual drivers).

But consumer light strings almost never use pure parallel wiring—at least not end-to-end. Why? Cost and safety. Running full 120V to hundreds of individual bulbs would require heavy insulation, bulky connectors, and strict spacing to prevent arcing. Instead, manufacturers use clever hybrids: multiple short series “substrings” wired in parallel to the main cord. A typical 100-light LED string may consist of four substrings of 25 LEDs each, all connected in parallel to the input wires. If one substring fails entirely (e.g., due to a broken wire or blown fuse in its section), only those 25 lights go dark—leaving the other 75 unaffected. That’s the “half-out” scenario you’re seeing: not randomness, but the failure of one parallel leg.

This architecture also explains why some strings have two distinct “halves”—each with its own fuse, rectifier, or controller. Look closely at the plug: many contain a small black box housing a thermal fuse, bridge rectifier (to convert AC to DC for LEDs), and sometimes even a microcontroller for chasing effects. That box feeds two independent output circuits. When the fuse blows in one leg—or the rectifier shorts—the corresponding substring dies instantly.

Decoding Your String: A Step-by-Step Identification Guide

You can determine your string’s wiring without a multimeter—just observation and logic. Follow this sequence:

- Count the bulbs and examine the plug. Strings with fewer than 50 incandescent bulbs are almost always series. Strings over 100 LEDs are almost always multi-substring parallel.

- Check for physical segmentation. Look for thicker “junction boxes” every 25–50 bulbs, or sections separated by noticeably heavier wire. These mark substring boundaries.

- Test continuity behavior. Remove one bulb from the dark section. If the rest of that section stays dark, it’s likely series *within* that segment. If removing it restores light to downstream bulbs, the socket has an active shunt—and the wiring is series with shunting.

- Inspect the fuse. Most plugs contain two fuses (one per leg in dual-output designs). Use needle-nose pliers to gently pull the small ceramic fuse cartridge from its holder. Hold it up to light—if the thin wire inside is severed, that leg is dead. Replace only with the exact amperage rating (usually 3A or 5A).

- Trace the copper. Cut power and carefully peel back insulation near a junction box. If you see two input wires splitting into multiple pairs going to different bulb groups—you’re looking at parallel substrings.

This process reveals more than wiring—it exposes design intent. A string built for durability will feature redundant shunts, gold-plated contacts, and sealed rectifiers. One built for $3.99 clearance will skip fuses, use bare copper leads prone to oxidation, and rely on a single-point shunt that fails catastrophically.

Real-World Case Study: The “Ghost Half” Patio String

Mark installed a 200-light warm-white LED string along his patio railing last October. By December, the first 100 lights glowed steadily—but the second 100 pulsed faintly every 3 seconds, then went dark. He replaced bulbs, checked outlets, and even swapped extension cords. Nothing changed.

A closer look revealed a small rectangular junction box after bulb #100—marked “Output A / Output B.” Inside, he found two identical 3A fuses. Using a multimeter on continuity mode, he discovered Fuse B was open. He replaced it with an identical 3A fast-blow fuse—and the second half blazed to life. But within 48 hours, it failed again.

He inspected the second substring’s first bulb socket and noticed green corrosion on the brass contacts. Cleaning them with electrical contact cleaner and a soft brush resolved the issue permanently. The root cause wasn’t the fuse—it was high resistance at the socket causing localized overheating, which tripped the thermal fuse repeatedly. This is classic parallel-substring behavior: the fuse protects the leg, but doesn’t fix the underlying stressor.

Series vs Parallel: Key Differences at a Glance

| Feature | Series Wiring | Parallel (Multi-Substring) Wiring |

|---|---|---|

| Voltage per bulb | Divided (e.g., 2.4V per bulb in 50-bulb string) | Full supply voltage per substring (e.g., 120V across 25-LED substring) |

| Effect of one dead bulb | Entire string or substring goes dark (unless shunted) | Only that bulb goes dark; rest unaffected |

| Effect of one open wire | All bulbs downstream fail | Only bulbs in that substring fail |

| Fuse protection | Rarely fused per section; single main fuse | Often one fuse per substring (2–4 fuses total) |

| Troubleshooting priority | Find first dead bulb or bad shunt | Check fuses first, then substrate connections |

| Typical use case | Older incandescent mini-lights, low-cost LED strings | Mid-to-high-end LED strings, commercial installations |

Expert Insight: What Lighting Engineers Prioritize

“Consumers assume ‘more bulbs = better quality.’ In reality, the most reliable strings use fewer LEDs per substring—20 instead of 50—because lower voltage drop means less heat buildup at connections. We also specify gold-flashed contacts and molded strain reliefs at every junction. That’s what prevents the ‘half-out’ syndrome—not marketing claims about ‘pro-grade LEDs.’” — Daniel Ruiz, Senior Design Engineer, LuminaString Technologies

Practical Troubleshooting Checklist

- ✅ Unplug the string and let it cool for 5 minutes (thermal fuses need reset time)

- ✅ Check and replace both fuses in the plug—even if only one appears blown

- ✅ Inspect the first non-working bulb’s socket for corrosion, bent contacts, or melted plastic

- ✅ Test voltage at the input terminals of each substring using a multimeter (should read ~120V AC if powered)

- ✅ Wiggle wires gently at junction boxes while powered (with caution)—intermittent light indicates a loose connection

- ✅ For LED strings, verify compatibility with dimmers or smart plugs (many require pure on/off switching)

- ✅ Replace bulbs only with manufacturer-specified replacements—mixing voltages or shunt types breaks the circuit balance

FAQ

Can I cut and rewire a series string to make it parallel?

No—never attempt this. Series strings lack the current-limiting resistors or drivers needed for parallel operation. Rewiring would subject bulbs to full line voltage, causing immediate burnout or fire hazard. Only professionally designed parallel strings include proper current regulation per branch.

Why do some new LED strings still go half-dark if they’re “parallel”?

They’re likely using a cost-optimized hybrid: two long series substrings (e.g., 50 LEDs each) wired in parallel. A single open circuit in one substring kills that entire 50-light section. True parallel would mean 200 individual circuits—which isn’t practical for plug-in decor lights.

Is there a way to prevent this without buying new lights every year?

Yes—focus on connection hygiene. Store strings loosely coiled (never tight knots), keep plugs in sealed bags with silica gel, and wipe contacts with isopropyl alcohol before seasonal use. Most “half-out” failures stem from oxidation and thermal cycling—not LED degradation.

Conclusion

That frustrating “half-out” moment isn’t a mystery—it’s a diagnostic clue written in electrons and solder. Whether your lights use vintage series wiring or modern parallel substrings, the behavior follows predictable electrical principles. Recognizing the pattern—where the darkness starts, how it propagates, and what components sit at the boundary—transforms you from a passive victim of faulty lights into an informed troubleshooter. You don’t need engineering credentials to extend your string’s life: just a fuse tester, a contact cleaner, and the knowledge that every junction box, every corroded socket, and every undersized fuse tells a story about why half the lights went out. Start this season by inspecting one string—not to fix it, but to understand it. Then share what you learn. Because the best holiday tradition isn’t perfect lights. It’s solving the puzzle together, one substring at a time.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?