Honey has been cherished for millennia—not just for its sweetness but also for its long shelf life and natural health benefits. Yet one of the most common surprises for new honey consumers is finding their jar thickened or turned grainy over time. This transformation, known as crystallization, is entirely natural. Far from indicating spoilage, it’s a sign of pure, unprocessed honey. Understanding why honey crystallizes—and how to reverse it—empowers you to enjoy this golden nectar in any form you prefer.

The Science Behind Honey Crystallization

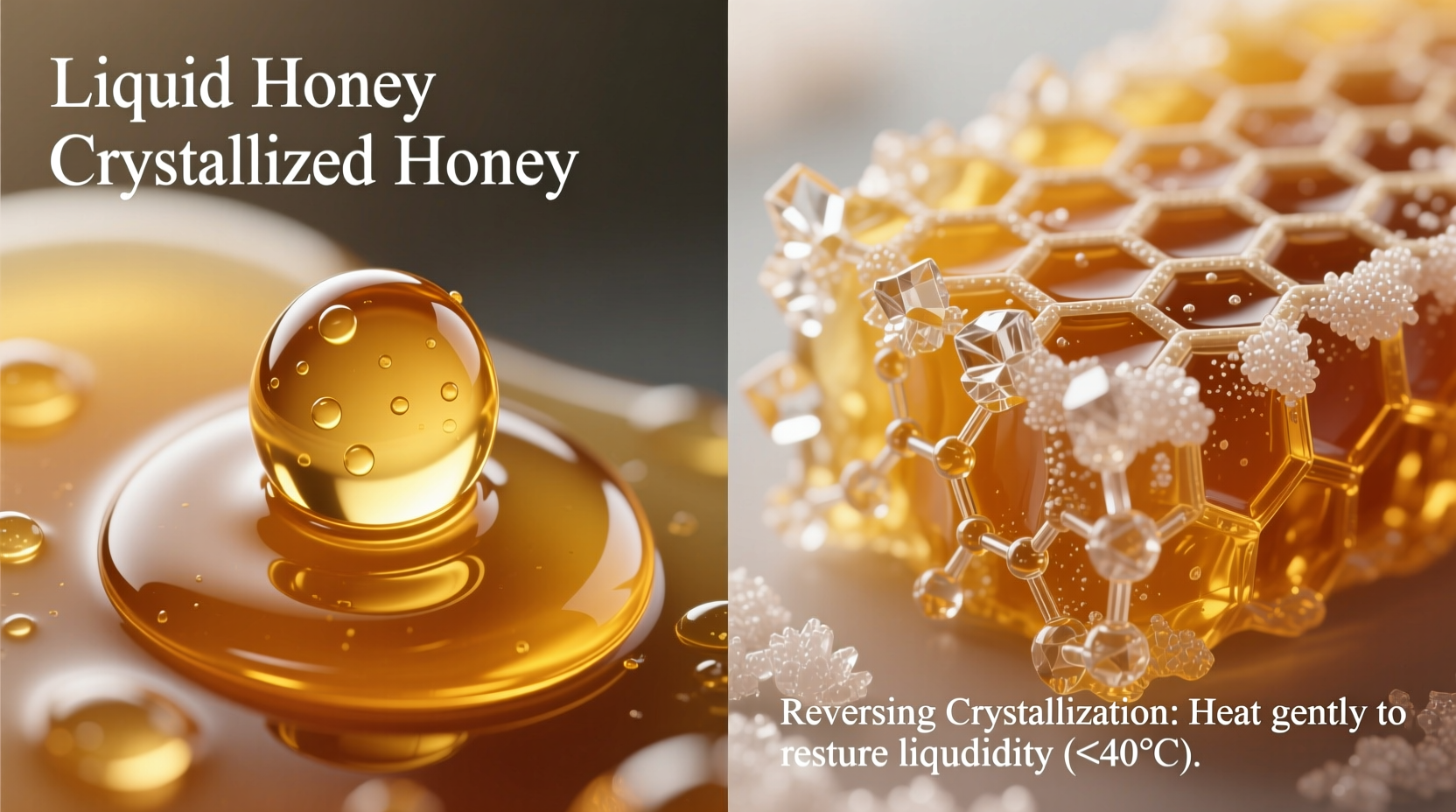

Honey is a supersaturated solution of sugars, primarily glucose and fructose. The ratio of these two sugars varies depending on the floral source, and that variation plays a crucial role in crystallization. Glucose tends to separate from the liquid more easily than fructose, forming tiny crystals. Over time, these crystals multiply and spread, turning the entire jar into a semi-solid state.

Crystallization is accelerated by several factors:

- Temperature: Cooler temperatures (between 50°F and 59°F or 10°C–15°C) promote faster crystallization.

- Water content: Honey with lower moisture content crystallizes more slowly.

- Pollen and particles: Raw honey contains microscopic pollen grains and wax bits that act as “seed” crystals.

- Storage conditions: Exposure to temperature fluctuations increases crystal formation.

Interestingly, some honeys crystallize within weeks (like clover or wildflower), while others—such as tupelo or acacia—can remain liquid for months or even years due to their high fructose content.

“Crystallized honey isn’t degraded—it’s actually a hallmark of authenticity. Processed honey often doesn’t crystallize because it’s been filtered and heated.” — Dr. Lydia Chen, Apiculturist and Food Scientist

How to Reverse Crystallized Honey Safely

Reversing crystallization is simple and effective when done correctly. The goal is to dissolve the sugar crystals without damaging honey’s delicate enzymes, flavor, or nutritional profile. Excessive heat can degrade quality, so gentle warming is essential.

Step-by-Step Guide to Liquefying Crystallized Honey

- Use warm water: Fill a pot or bowl with warm water (no hotter than 110°F or 43°C).

- Submerge the jar: Place the sealed honey container in the water. If using a plastic container, transfer honey to a glass jar first to avoid chemical leaching.

- Wait patiently: Allow the jar to sit in the water bath for 15–30 minutes. Stir gently if possible (if lid allows).

- Repeat as needed: Replace the water as it cools. Continue until crystals fully dissolve.

- Avoid microwaves: Microwaving creates uneven hot spots and may destroy beneficial compounds.

Do’s and Don’ts of Managing Crystallized Honey

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Store honey at room temperature (70°F/21°C) | Refrigerate honey (speeds up crystallization) |

| Use gentle heat (water bath method) | Boil honey or use direct stove heat |

| Keep lids tightly sealed to prevent moisture absorption | Leave honey uncovered or expose to humidity |

| Stir crystallized honey into warm tea or sauces | Microwave honey in closed containers |

| Embrace crystallized honey for spreading or baking | Assume crystallization means spoilage |

Real Example: A Baker’s Experience with Crystallized Honey

Sophie Ramirez, a home baker from Portland, Oregon, once discarded two jars of raw wildflower honey after noticing they had turned cloudy and firm. “I thought it had gone bad,” she recalls. After learning about crystallization from a local beekeeper, she began intentionally storing her honey in a cool pantry drawer—knowing she could always liquefy it when needed.

Now, Sophie uses crystallized honey directly in recipes like oatmeal cookies and granola bars, where its spreadable texture blends evenly into dry ingredients. When making glazes or dressings, she gently warms the jar in a bowl of hot water. “It’s actually more convenient now,” she says. “I save time not waiting for liquid honey to drizzle slowly off the spoon.”

Practical Tips for Preventing and Managing Crystallization

While you can’t completely stop crystallization in raw honey, you can influence its timing and texture:

- Choose slow-crystallizing varieties: Acacia, sage, and tupelo honeys stay liquid longer due to higher fructose levels.

- Buy smaller jars: Smaller quantities are used faster, reducing the chance of prolonged storage leading to crystallization.

- Freeze honey for long-term storage: Honey won’t freeze solid due to its low moisture and high sugar content, but freezing halts crystallization indefinitely. Thaw at room temperature when needed.

- Blend textures: Mix a small amount of liquid honey into crystallized batches to help slow further solidification.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is crystallized honey safe to eat?

Absolutely. Crystallized honey is perfectly safe and retains all its flavor, aroma, and nutritional benefits. It’s still antibacterial, antioxidant-rich, and suitable for cooking, baking, or eating straight from the spoon.

Can I eat honey that has both liquid and solid layers?

Yes. This separation is normal during partial crystallization. Simply stir the contents together before use, or gently warm to return it to a uniform liquid state.

Does pasteurized honey crystallize?

Rarely and very slowly. Commercial pasteurized honey is heated and finely filtered to remove pollen and microcrystals, which delays crystallization. However, this process also diminishes many of the natural enzymes and phytonutrients found in raw honey.

Conclusion: Embrace the Natural Cycle of Honey

Crystallization is not a flaw—it’s a testament to honey’s purity and minimal processing. By understanding the natural chemistry at play, you gain control over texture and usability without compromising quality. Whether you prefer your honey runny for drizzling or thick for spreading, you now have the knowledge to manage its state with confidence.

Instead of discarding crystallized honey, celebrate it as part of the journey from hive to table. With proper techniques, you can reverse it safely—or simply enjoy it as nature intended.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?