It’s a familiar sensation: a small, nagging itch appears on your arm, and without thinking, you reach over and scratch it. Almost instantly, relief follows—sometimes even pleasure. But why does scratching an itch feel so satisfying? Behind this simple act lies a complex interplay of nerves, brain chemistry, and evolutionary biology. This article explores the deeper mechanisms that make scratching feel good, how the brain processes itch and relief, and what happens when this system goes awry.

The Biology of Itch: More Than Just Skin Deep

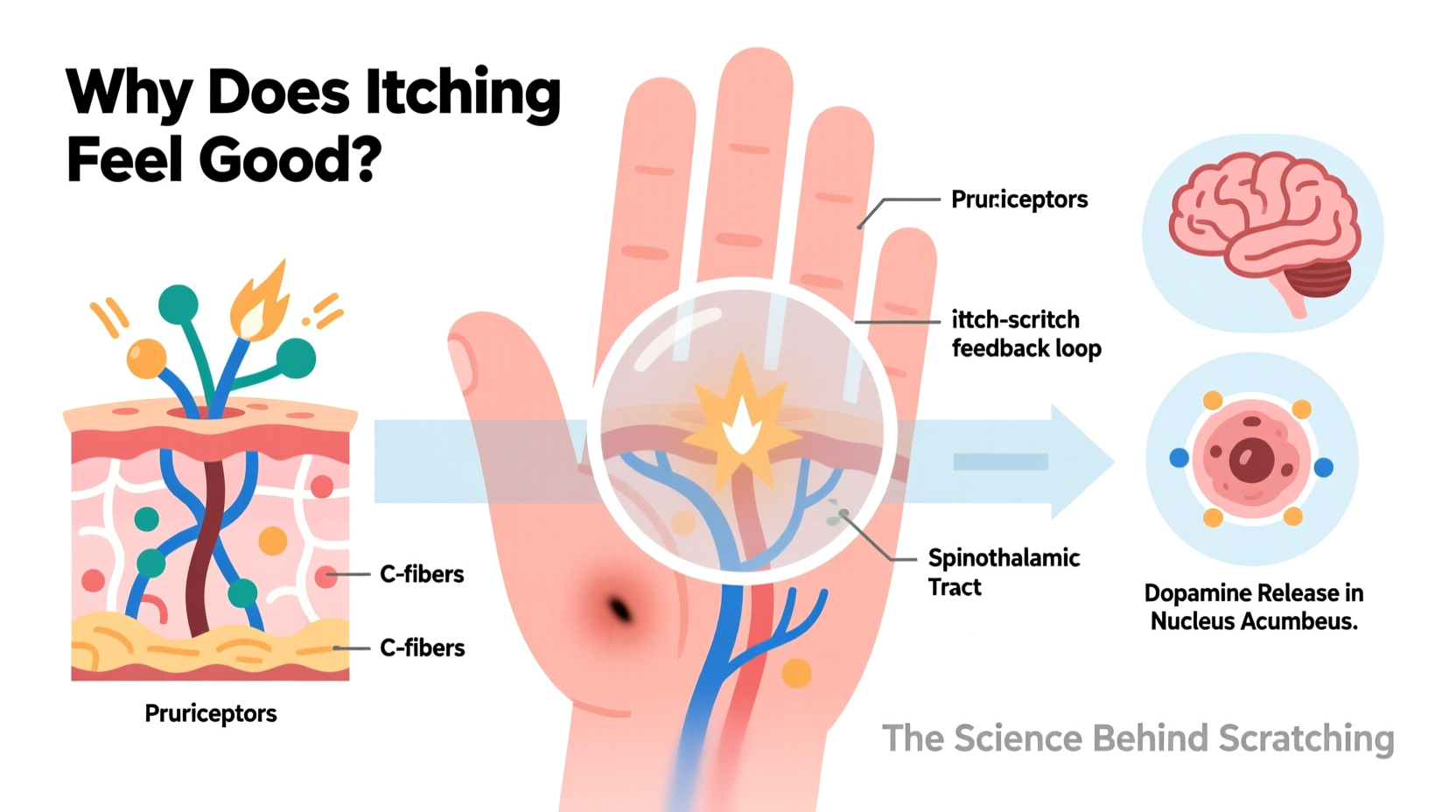

Itching, or pruritus, is a protective sensation designed to alert the body to potential threats on the skin—such as insects, irritants, or allergens. Specialized nerve fibers called C-fibers detect these stimuli and send signals through the spinal cord to the brain. Unlike pain, which prompts withdrawal, itch triggers a desire to scratch, aiming to remove the offending agent.

Scientists have identified specific receptors and neurotransmitters involved in the itch pathway. One key player is histamine, released during allergic reactions, which activates H1 receptors on nerve endings. However, not all itching is histamine-driven. Chronic conditions like eczema or kidney disease involve non-histaminergic pathways, making them less responsive to antihistamines.

What makes itching unique is its dual nature—it starts in the periphery but is ultimately interpreted by the brain. The somatosensory cortex maps where the itch occurs, while emotional centers like the anterior cingulate cortex influence how bothersome it feels.

Why Scratching Feels Good: The Brain's Reward System

The moment you scratch an itch, something remarkable happens in your brain. Neuroimaging studies using fMRI have shown that scratching reduces activity in brain regions associated with unpleasant sensations, such as the insula and prefrontal cortex. At the same time, it activates areas tied to reward and pleasure—the same circuits lit up by eating delicious food or listening to enjoyable music.

This response involves the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter linked to motivation and reward. When you scratch, dopamine floods the nucleus accumbens, creating a brief but powerful sense of satisfaction. This explains why scratching feels addictive—especially when the itch is persistent.

“Scratching provides immediate negative reinforcement: you remove discomfort, which the brain interprets as a reward.” — Dr. Gil Yosipovitch, Professor of Dermatology and Itch Research Specialist

The brain doesn’t distinguish sharply between physical relief and emotional gratification. That’s why people sometimes scratch even when there’s no real trigger—a habit reinforced by the brain’s craving for that dopamine hit.

The Itch-Scratch Cycle: When Relief Becomes a Problem

While scratching offers short-term relief, it can also perpetuate a dangerous loop. Mechanical stimulation from scratching damages skin cells, prompting the release of inflammatory chemicals like serotonin and substance P. These substances sensitize nerve endings, making the area more prone to future itching—even in the absence of an original cause.

This self-perpetuating pattern is known as the itch-scratch cycle. Over time, repeated scratching leads to lichenification—thickened, leathery skin that itches more easily. Conditions like atopic dermatitis thrive in this environment, turning manageable symptoms into chronic discomfort.

Breaking the cycle requires interrupting both the physical and neurological components. Strategies include cooling the skin (to reduce nerve signaling), using moisturizers (to repair the barrier), and behavioral techniques (to retrain the brain’s response).

| Stage | Physiological Process | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initial Itch | Nerve fibers detect irritant; signal sent to brain | Urge to scratch arises |

| 2. Scratching | Dopamine released; pain signals suppressed | Temporary pleasure and relief |

| 3. Skin Damage | Inflammation increases; new mediators released | Increased sensitivity and renewed itching |

| 4. Repetition | Cycle repeats; neural pathways strengthen | Chronic itching and possible infection |

Psychological and Emotional Dimensions of Itching

Itching isn't purely physical—it’s deeply influenced by mood, attention, and stress. Anxiety and depression are strongly linked to heightened itch perception. Patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) may engage in compulsive scratching, even in the absence of a rash. Similarly, seeing someone else scratch can trigger the urge in you—a phenomenon known as \"contagious itching.\"

A real-world example illustrates this complexity: Sarah, a 34-year-old teacher, developed severe scalp itching after starting a high-pressure job. No underlying skin condition was found. Her dermatologist recommended cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) alongside topical treatments. Over eight weeks, Sarah learned mindfulness techniques to redirect her focus when the urge to scratch arose. Her symptoms improved significantly—not because the cause was physical, but because her brain’s response was recalibrated.

This case highlights how central the mind is in processing itch. Perception matters as much as pathology.

Practical Tips to Manage Itching Without Over-Scratching

Understanding the science is only useful if it leads to better habits. Here are actionable steps to manage itching effectively:

- Keep nails short to minimize skin injury when scratching inadvertently.

- Apply cool compresses or calamine lotion to soothe irritated skin.

- Use fragrance-free moisturizers daily to maintain skin barrier integrity.

- Wear loose, breathable clothing made from natural fibers like cotton.

- Practice stress-reduction techniques such as deep breathing or meditation.

Checklist: Breaking the Itch-Scratch Cycle

- Identify triggers (e.g., dry air, allergens, stress)

- Hydrate skin with hypoallergenic moisturizer twice daily

- Replace scratching with safer alternatives (tapping, pressing)

- Use prescribed topical treatments consistently

- Seek psychological support if itching affects mental health

Frequently Asked Questions

Can scratching ever be beneficial?

Yes—brief, gentle scratching can help remove irritants and provide temporary relief. However, prolonged or aggressive scratching causes micro-tears in the skin, increasing inflammation and infection risk. Moderation is key.

Why do some people itch more at night?

Nighttime itching intensifies due to natural circadian rhythms. Cortisol levels (which suppress inflammation) drop at night, while body temperature rises, increasing blood flow to the skin. Additionally, fewer distractions make people more aware of minor sensations.

Are there medications that target the pleasure of scratching?

Emerging therapies aim to modulate the brain’s reward response to scratching. Some antidepressants, like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have shown promise in reducing compulsive scratching behaviors by altering neurotransmitter balance.

Conclusion: Harnessing Knowledge for Healthier Skin and Mind

The pleasure of scratching is not just a quirk of human behavior—it’s a sophisticated survival mechanism gone slightly off-track in modern environments. By understanding the neuroscience behind itch and relief, we gain power over our responses. Instead of succumbing to automatic scratching, we can choose smarter, safer ways to find comfort.

Whether you're dealing with occasional dry skin or managing a chronic condition, applying this knowledge can improve both physical and emotional well-being. The next time an itch arises, pause. Recognize the biological drama unfolding beneath your skin—and respond with intention.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?