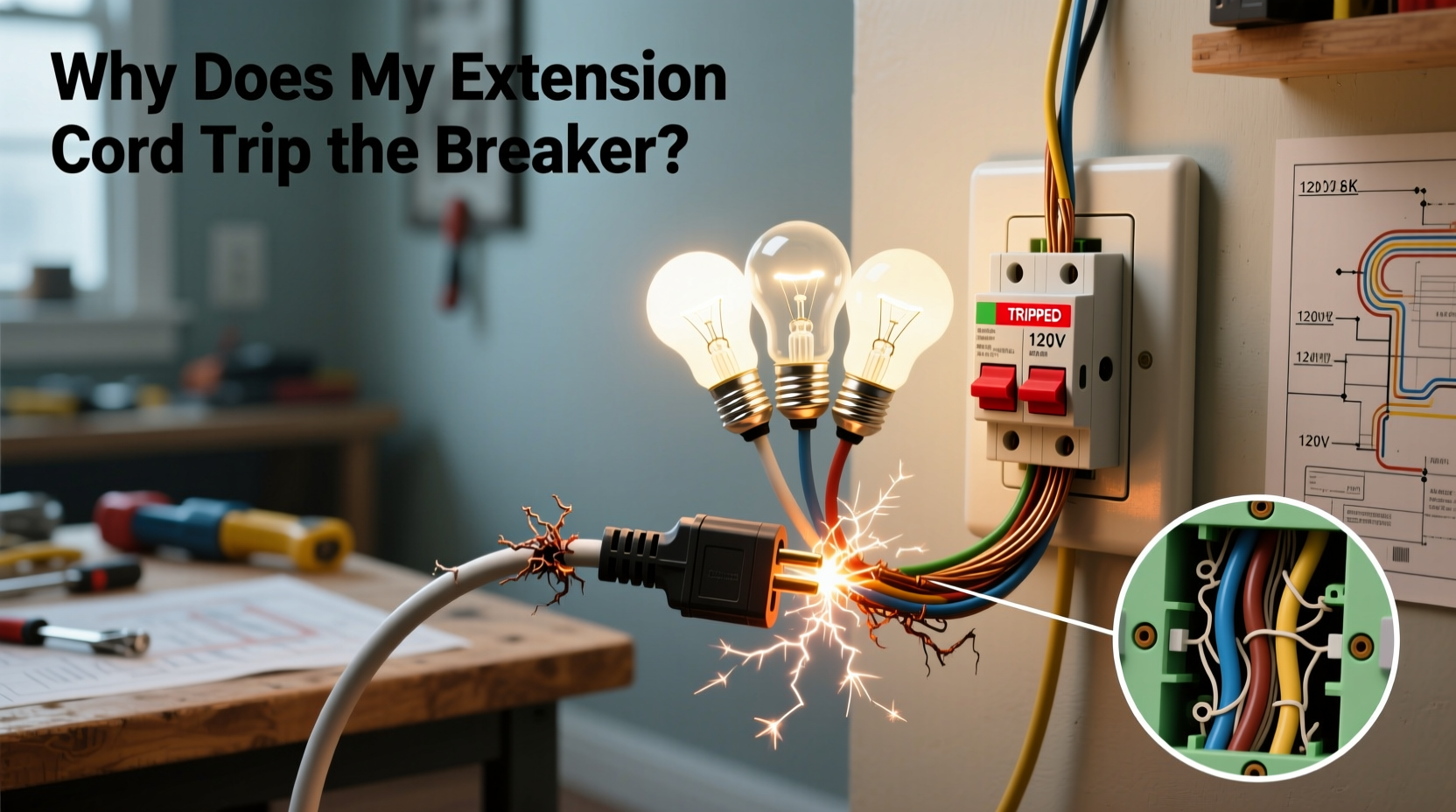

Tripping a circuit breaker the moment you plug in holiday lights, outdoor stringers, or even a single lamp via an extension cord isn’t just inconvenient—it’s a clear warning sign. This behavior points to an underlying electrical issue that, if ignored, can escalate from nuisance to hazard: overheating wires, damaged insulation, or even fire risk. Unlike flickering lights or intermittent outages, a breaker tripping *at the instant of connection* reveals a fault that occurs before current flows normally—meaning something is fundamentally wrong with the path electricity is being asked to take. Understanding why this happens requires looking beyond “the cord looks fine” and examining the interplay between load, wiring integrity, grounding, and circuit protection design.

How Circuit Breakers Actually Work (and Why They Trip)

Circuit breakers are safety devices—not convenience switches. They monitor two primary conditions: overcurrent and ground faults. Standard thermal-magnetic breakers respond to sustained overloads (e.g., too many watts on a 15-amp circuit) by heating a bimetallic strip until it bends and triggers the trip mechanism. But they also react instantly to short circuits—where hot and neutral wires contact directly—or ground faults—where current escapes its intended path (e.g., through moisture, damaged insulation, or faulty equipment).

When a breaker trips *the second* a light string is plugged into an extension cord, it almost always indicates one of two things: a dead short (near-zero resistance path) or a severe ground fault. These cause instantaneous current spikes—often hundreds or thousands of amps—far exceeding the breaker’s rating (e.g., 15A or 20A). The magnetic component of the breaker detects this surge in milliseconds and opens the circuit before heat builds. This is intentional and life-saving—but it means the problem is present *before* the lights even turn on.

Top 5 Causes—and How to Identify Each

Diagnosing the root cause requires methodical elimination. Don’t assume it’s “just the lights.” Start at the point of failure—the plug—and work backward.

1. Damaged or Compromised Extension Cord

Physical damage is the most common culprit. Cords left outdoors, run under rugs, pinched in doors, or coiled tightly while hot degrade insulation. A nicked wire inside the jacket may not be visible but can allow hot and neutral conductors to touch when flexed during plugging. Even minor abrasion near the plug end—especially where the cord enters the housing—can expose bare copper.

2. Moisture Intrusion

Water doesn’t need to flood the cord to cause trouble. Condensation inside an outdoor-rated cord left in a damp garage, or rain-soaked connections on patio lights, creates conductive paths. Ground-fault circuit interrupters (GFCIs) trip even more readily than standard breakers under these conditions—but standard breakers will still trip if moisture bridges conductors.

3. Faulty Light String or Fixture

A single crushed bulb socket, corroded contacts, or internal wire separation in a light string can create a short when voltage is applied. Older incandescent mini-lights often fail this way: one bulb burns out and the shunt fails, causing adjacent bulbs to overheat and short internally. LED strings are less prone—but cheap, uncertified models frequently use substandard PCBs or solder joints that crack and short when bent or plugged.

4. Overloaded Circuit (Less Likely for Instant Trips—but Still Possible)

While overloads usually cause *delayed* tripping (after 1–5 minutes), some modern breakers have sensitive thermal profiles. If your circuit is already near capacity (e.g., refrigerator + microwave + coffee maker running), adding even a modest 200W string *could* push it over the edge—especially if the breaker is aging or undersized. However, this rarely causes *instantaneous* tripping unless combined with another fault.

5. Grounding Issues or Reverse Polarity

If the extension cord or outlet has reversed hot/neutral wiring—or if the ground pin is compromised—the breaker may detect an abnormal current imbalance. This is especially true with GFCI-protected circuits, which monitor the difference between hot and neutral current flow. A mismatch as small as 4–6mA triggers a trip. While not always visible, reversed polarity is easily tested with a $10 outlet tester.

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol

Follow this sequence—strictly in order—to isolate the fault without guesswork or risk:

- Unplug everything. Disconnect all devices from the extension cord and the cord itself from the outlet. Reset the breaker.

- Test the outlet alone. Plug a known-good device (e.g., lamp) directly into the same outlet. If it trips, the issue is in the outlet, wiring, or panel—not the cord or lights.

- Inspect the cord visually and tactilely. Look for cuts, kinks, melted areas, or stiffness near plugs. Gently bend the cord near both ends while listening for crackling or feeling for grittiness—signs of internal conductor damage.

- Test the cord independently. Plug the cord (no lights attached) into the outlet. If it trips, the cord is faulty. Discard it immediately.

- Test lights without the cord. Plug the light string directly into the outlet. If it trips, the lights are defective. If not, the issue is interaction between cord and lights—or cord alone was misdiagnosed.

- Check for moisture. Wipe down all plugs and sockets. Let them air-dry for 2+ hours in a warm, dry room before retesting.

- Verify polarity and grounding. Use a three-light outlet tester on both the source outlet and any downstream outlets the cord feeds. Correct any “open ground,” “hot/neutral reverse,” or “open neutral” readings first.

Extension Cord Safety: Ratings, Usage, and What “Heavy-Duty” Really Means

Not all extension cords are created equal—and “heavy-duty” is often marketing, not engineering. Real safety depends on three specifications: gauge (wire thickness), length, and UL listing for intended use (indoor vs. outdoor, temporary vs. permanent).

| Gauge (AWG) | Max Recommended Load (120V) | Safe Length for 15A Circuit | Common Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 AWG | 1,300W (≈10.8A) | Up to 50 ft | Indoor lamps, small electronics |

| 14 AWG | 1,800W (≈15A) | Up to 100 ft | Outdoor tools, medium-duty lighting |

| 12 AWG | 2,400W (≈20A) | Up to 150 ft | Power tools, large light displays, job sites |

| 10 AWG | 3,000W (≈25A) | Up to 200 ft | High-wattage heaters, commercial signage |

Using a 16 AWG cord for a 1,200W stringer—even if it “works”—causes voltage drop, overheating, and premature insulation failure. Longer cords compound resistance; a 100-ft 16 AWG cord can lose 15% voltage at full load, stressing LEDs and increasing heat buildup. Always match cord gauge to both wattage *and* length. And never daisy-chain extension cords—a leading cause of fire incidents, per the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC).

Real-World Case Study: The Garage Holiday Display

Mark, a homeowner in Ohio, installed 12 strands of LED icicle lights (total ~720W) for his garage eaves using a single 100-ft, 14 AWG outdoor-rated cord. For two years, it worked—until one December morning, the breaker tripped instantly when he plugged in the first strand. He assumed the lights were faulty and replaced them—only to face the same trip. He then tried a different outlet (same circuit), same result. Frustrated, he called an electrician.

The technician discovered three issues: First, the cord had been stored coiled tightly in a damp basement all summer, causing micro-fractures in the PVC jacket. Second, the outlet feeding the cord was improperly grounded (confirmed with tester). Third, Mark had added two new smart-plug adapters to the same circuit—pushing baseline load to 14.2A before adding lights. The combination of degraded insulation (creating a latent ground path) and marginal headroom meant the moment voltage hit the cord, leakage current exceeded the breaker’s tolerance.

Resolution: Replace the cord with a 12 AWG model, install a dedicated 20A circuit for seasonal lighting, and correct the grounding. No more trips—and no more guessing.

Expert Insight: What Licensed Electricians See Most Often

“Ninety percent of ‘mystery’ breaker trips with extension cords trace back to one of three things: moisture trapped in a cord end, physical damage hidden under the plug housing, or using indoor-rated cords outside—even if they’re labeled ‘weather-resistant.’ Real outdoor cords have thermoplastic elastomer (TPE) jackets that remain flexible in cold and resist UV degradation. PVC indoor cords become brittle and crack, exposing wires. Always check the UL label: ‘SOW’ or ‘SOOW’ means outdoor-rated. ‘SJTW’ is acceptable—but ‘SJT’ is indoor only.” — Carlos Mendez, Master Electrician & NFPA 70E Trainer, 22 years in residential diagnostics

Troubleshooting Checklist

- ☑️ Verify the breaker resets fully (push firmly past “off” to “on”)

- ☑️ Test outlet with a known-working device (lamp, phone charger)

- ☑️ Inspect cord for cuts, swelling, discoloration, or stiffness near plugs

- ☑️ Confirm cord is rated for outdoor use *and* matches load/length requirements

- ☑️ Use an outlet tester to validate grounding and polarity

- ☑️ Dry all connectors thoroughly if moisture is suspected

- ☑️ Plug lights directly into outlet—bypassing cord—to isolate fault location

- ☑️ Check total circuit load: Add wattage of all devices on the same breaker

FAQ

Can a tripping breaker damage my lights or cord?

Yes—repeated tripping stresses components. Each surge subjects LEDs, drivers, and cord insulation to thermal shock. A cord that trips once may be salvageable; one that trips three times likely has internal damage and should be retired. Lights subjected to repeated short-circuit surges often suffer latent failures—dimming, color shift, or intermittent operation weeks later.

Why does it only trip when I plug in the lights—but not when the cord is empty?

Because the fault exists *within the load*, not the cord alone. An intact cord presents high resistance (safe). When connected to a defective light string, the short or ground fault completes a low-resistance path, allowing massive current flow. The breaker responds to the completed circuit—not the cord in isolation.

Is it safe to replace a tripped breaker with a higher-amp one?

No—this is extremely dangerous. Breakers protect wiring. A 20A breaker on 14 AWG wire (rated for 15A) allows unsafe current levels, causing insulation to overheat and potentially ignite. Upgrading a breaker requires upgrading the entire circuit’s wiring, outlet, and panel connections—a job for a licensed electrician. Never “fix” overload issues with bigger breakers.

Conclusion: Safety Isn’t Optional—It’s Electrical Code

Your extension cord tripping the breaker isn’t a quirk of bad luck or inferior gear. It’s physics enforcing a boundary: electricity demands respect for resistance, insulation, grounding, and load limits. Every trip is data—a signal that something violates fundamental safety rules. Ignoring it invites risk; diagnosing it builds confidence and competence. You don’t need to be an electrician to troubleshoot effectively—just systematic, observant, and willing to stop when uncertainty arises. Replace damaged cords without hesitation. Match specs to real-world use. Respect ampacity ratings like speed limits. And when in doubt—call a professional. Your home’s wiring system is a closed ecosystem; one weak link compromises the whole.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?