Handmade soap is a rewarding craft that blends chemistry, creativity, and care. But nothing is more frustrating than cutting into a fresh batch only to find it crumbling apart before it even reaches the shower. Crumbly soap isn’t just disappointing—it can signal deeper issues in formulation or process, particularly involving lye (sodium hydroxide) ratios. Understanding why this happens and how to correct it—without compromising safety—is essential for any soap maker, from beginner to advanced.

Crumbling typically occurs when the saponification process—the chemical reaction between fats and lye—is unbalanced. Too much or too little lye, incorrect measurements, or poor curing conditions can all contribute. The good news? With precise adjustments and proper techniques, you can consistently produce firm, long-lasting bars. This guide breaks down the science behind crumbling soap, walks through safe lye correction methods, and offers actionable steps to improve your next batch.

Understanding Why Homemade Soap Crumbles

The integrity of a soap bar depends on a stable matrix formed during saponification. When this process is disrupted, the resulting structure becomes weak and brittle. Several factors can lead to crumbling, but most trace back to imbalances in ingredients or errors in execution.

- Lye imbalance: Too much lye leaves excess alkali that doesn't fully react, weakening the bar. Too little lye means not all oils are converted into soap, leaving soft, unstable fats.

- Inaccurate measurements: Weighing errors, especially with lye or water, can throw off the entire recipe.

- Poor mixing or incomplete emulsification: If oils and lye solution don’t fully blend, pockets of unreacted materials form, leading to structural weakness.

- Low-hardness oils: High proportions of soft oils like olive or sunflower can create softer bars that degrade faster if not balanced with harder fats like coconut or palm.

- Insufficient curing time: Fresh soap needs 4–6 weeks to fully harden and stabilize. Cutting too early leads to fragility.

- Temperature fluctuations: Pouring at incorrect temperatures or exposing soap to drafts can cause cracking and uneven setting.

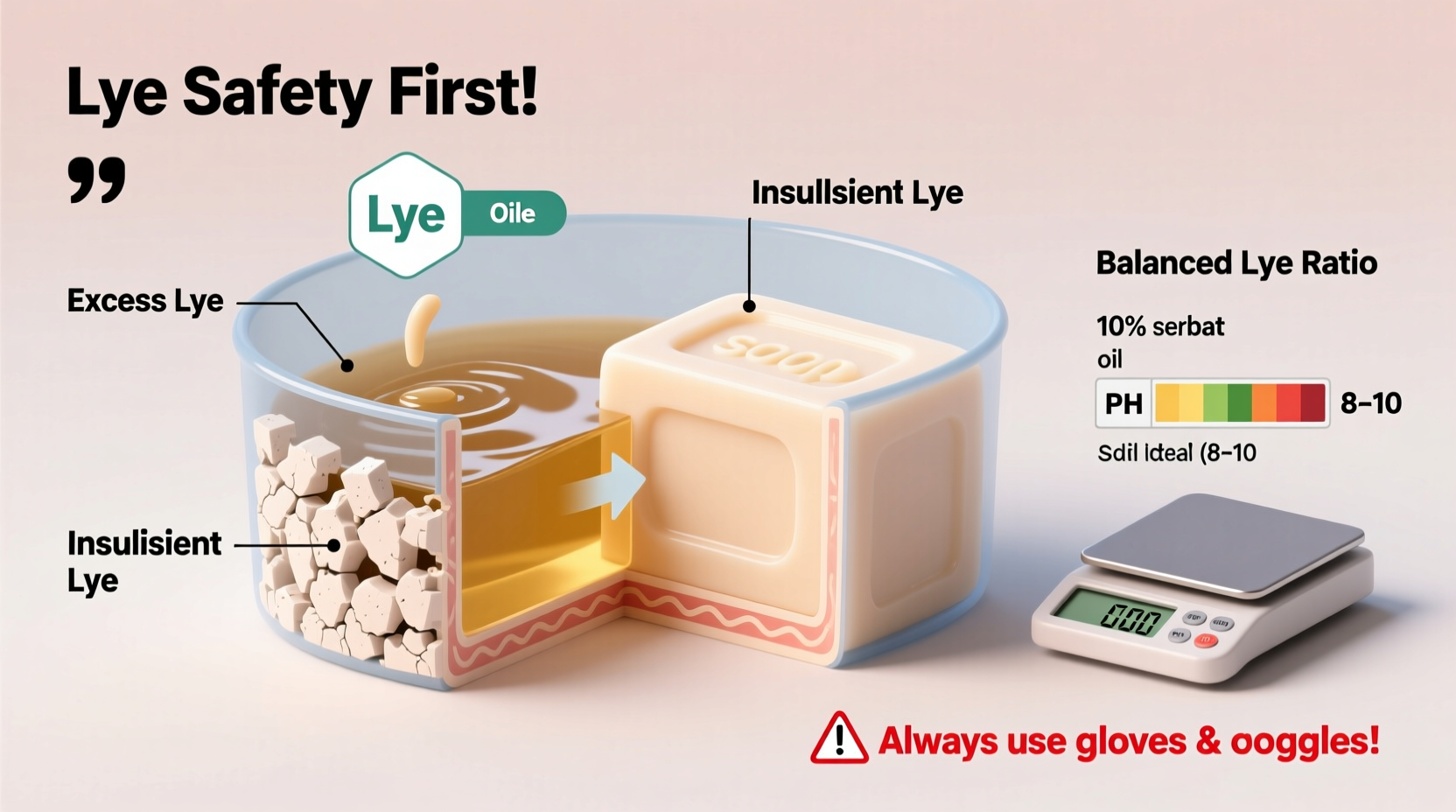

How Lye Ratio Impacts Soap Strength and Stability

Lye (sodium hydroxide) is the catalyst that transforms oils into soap. The exact amount needed depends on the saponification value (SAP value) of each oil—a measure of how much lye is required to fully convert a given fat into soap. Each oil has a unique SAP value, so substituting one oil for another without recalculating lye can result in imbalance.

A common misconception is that “more lye makes harder soap.” In reality, excess lye increases pH and creates caustic, irritating bars that may crumble due to internal stress. Conversely, under-lyed soap contains unsaponified oils that oxidize over time, leading to rancidity and disintegration.

“Precision in lye calculation isn’t just about safety—it’s the foundation of a stable, long-lasting bar.” — Dr. Lydia Chen, Cosmetic Chemist and Soap Formulation Specialist

To prevent crumbling, aim for a balanced formula with a slight superfat (3–7%), meaning a small percentage of oils remain unreacted to enhance moisturizing properties without sacrificing stability. Going beyond 8% superfat increases softness and spoilage risk, especially with unsaturated oils.

Safely Correcting Lye Ratios: A Step-by-Step Guide

If your soap is crumbling, don’t assume more lye is the answer. Instead, follow this methodical approach to diagnose and adjust your formula safely.

- Review your original recipe: Write down every oil used, their weights, and the lye and water amounts. Double-check entries for typos.

- Run it through a lye calculator: Use a trusted tool like SoapCalc or Bramble Berry’s Lye Calculator. Input exact oil weights and check the recommended lye amount at your desired superfat level.

- Compare actual vs. calculated lye: Did you use more or less than recommended? Even a 2-gram difference can affect texture.

- Analyze oil composition: Calculate the percentage of hard oils (coconut, palm, cocoa butter) versus soft oils (olive, sweet almond, grapeseed). Bars should contain at least 30–40% hard oils for durability.

- Adjust future batches: Modify oil ratios or superfat levels based on findings. For example, reduce olive oil from 100% to 70% and add 20% coconut oil and 10% shea butter for balance.

- Test the pH (optional): After curing, test a sliver of soap with pH strips. Safe range is 8–10. Above 10 suggests excess lye; below 8 may indicate incomplete saponification.

Never attempt to \"fix\" a batch of crumbly soap by adding more lye after trace—this is extremely hazardous and can result in unpredictable reactions. Instead, re-batch (hot process) the soap with additional hard oils if it’s too soft, or discard unsafe batches showing signs of lye-heavy texture (gritty feel, strong odor, skin irritation).

Do’s and Don’ts of Lye Handling and Recipe Design

Maintaining safety while achieving optimal results requires discipline. The following table outlines best practices and common pitfalls.

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Use a digital scale for all ingredients | Measure lye or oils by volume (cups/spoons) |

| Wear gloves, goggles, and long sleeves when handling lye | Work without eye protection or ventilation |

| Recalculate lye whenever changing oils or quantities | Reuse old recipes without verifying calculations |

| Stick to 3–7% superfat for balanced bars | Superfat above 10% unless making specialty soaps |

| Cure soap for 4–6 weeks before use | Use or sell soap within 1–2 weeks of pouring |

| Label all batches with date, ingredients, and lye amount | Store unlabeled soap where others might use it |

Real Example: Fixing a Crumbling Olive Oil Batch

Sarah, a home crafter in Oregon, made her first batch using 100% olive oil and followed an online recipe she found. After four weeks of curing, the bars were soft, mushy, and began to flake when handled. Confused, she tested the pH and got a reading of 9.5—within normal range—but the texture remained poor.

She consulted a lye calculator and discovered her recipe had a 12% superfat due to a miscalculated lye amount. While not dangerously caustic, the high oil content prevented full hardening. She adjusted her next batch to 70% olive oil, 20% coconut oil, and 10% shea butter, recalculated lye, and cured for six weeks. The new bars were firm, creamy-lathering, and showed no signs of crumbling.

This case illustrates that even non-caustic soap can fail structurally due to improper oil balance. Superfat matters, but so does fat diversity.

Essential Checklist for Stronger, Non-Crumbling Soap

Follow this checklist before starting your next batch to avoid common pitfalls:

- ✅ Use a reliable lye calculator and input exact oil weights

- ✅ Confirm lye amount matches calculated recommendation

- ✅ Include at least 30% hard oils (e.g., coconut, palm, or cocoa butter)

- ✅ Limit superfat to 3–7% for standard bars

- ✅ Measure all ingredients by weight, not volume

- ✅ Mix thoroughly until stable trace is reached

- ✅ Insulate mold properly and avoid drafts during gel phase

- ✅ Cure cut bars in a cool, dry, well-ventilated area for 4–6 weeks

- ✅ Test pH and texture before declaring batch successful

- ✅ Label and date each batch for tracking

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I add extra lye to make my soap harder?

No. Adding more lye than required creates a caustic, unsafe product that can irritate or burn the skin. Hardness comes from oil balance and curing—not excess lye. Use harder oils instead.

Why did my soap crumble even though I used a recipe from a trusted source?

Even good recipes can go wrong if measurements are off, substitutions aren’t recalculated, or environmental factors (like humidity) interfere. Always verify lye amounts with a calculator, especially if modifying ingredients.

Is crumbly soap safe to use?

It depends. If the soap feels gritty, smells strongly of lye, or stings the skin, it likely contains unreacted sodium hydroxide and should be discarded. If it’s simply soft and powdery due to high soft-oil content, it may be safe but ineffective. When in doubt, rebatch or compost it.

Final Thoughts: Building Confidence Through Precision

Crumbling soap doesn’t mean failure—it’s feedback. Each batch teaches something valuable about balance, measurement, and patience. The key to consistent success lies in respecting the chemistry of saponification and approaching each step with accuracy and care.

By auditing your process, recalculating lye with confidence, and balancing your oils wisely, you’ll transform fragile bars into luxurious, durable creations. Remember: great soap isn’t made overnight. It’s shaped by attention to detail, thoughtful adjustments, and a commitment to safety at every stage.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?