Many people notice a clicking, popping, or cracking sound in their knees when they squat. While this can be alarming, it’s not always a sign of damage. In fact, occasional knee noise is common and often harmless. However, persistent or painful clicking may indicate an underlying issue that needs attention. Understanding the difference between benign joint mechanics and potential injury is essential for maintaining long-term knee health, especially for athletes, fitness enthusiasts, and anyone who regularly performs deep knee bends.

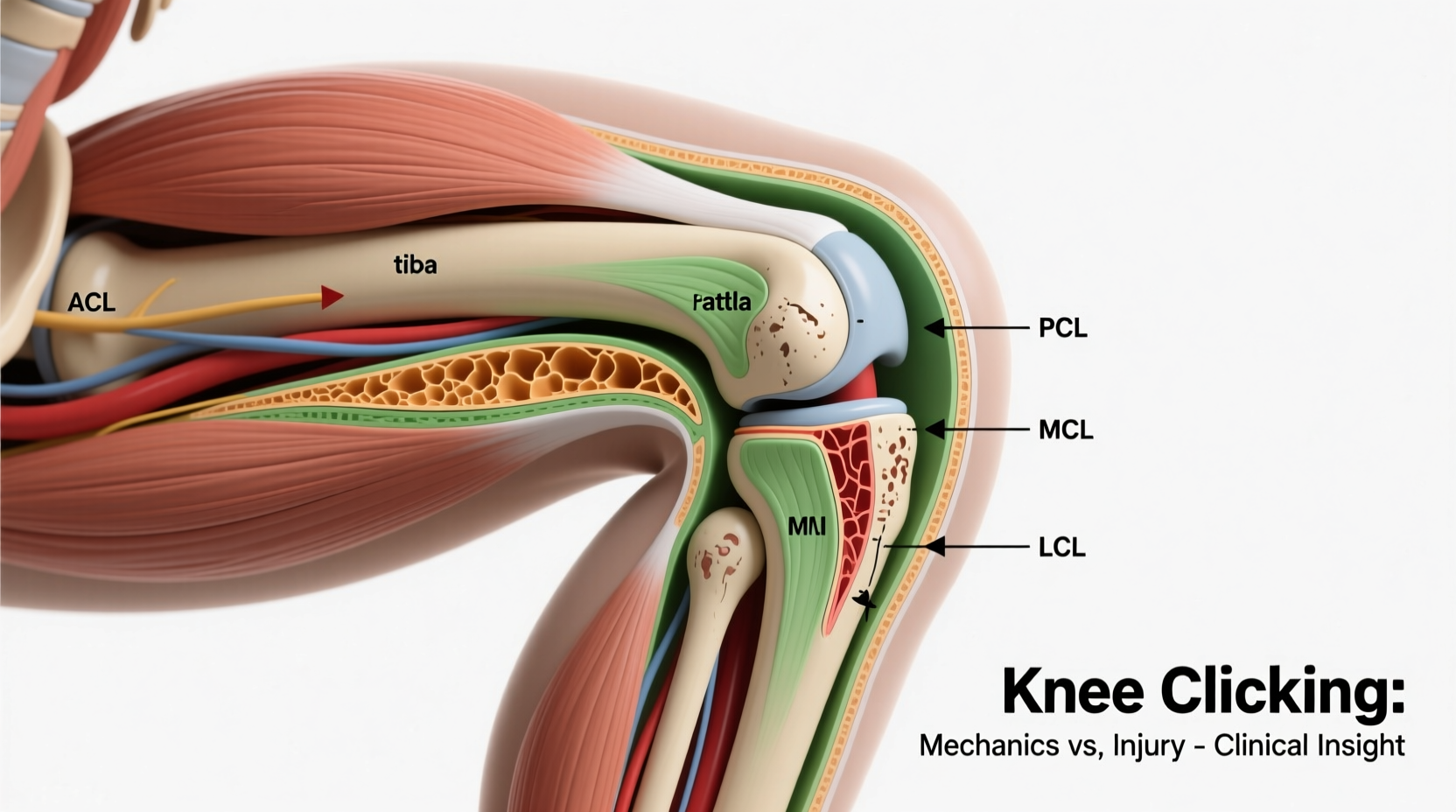

The knee is one of the most complex joints in the body, bearing significant loads during movement. When you squat, multiple structures—including bones, cartilage, ligaments, tendons, and synovial fluid—interact dynamically. These interactions can produce audible sounds. The key question isn’t just whether your knee clicks, but when, how often, and whether it’s accompanied by pain, swelling, or instability.

How Knee Clicking Works: The Science Behind Joint Sounds

The technical term for joint noises like clicking or popping is crepitus. Crepitus occurs due to several physiological mechanisms:

- Cavitation: When pressure changes rapidly within the joint capsule, tiny gas bubbles (mostly nitrogen and carbon dioxide) form and collapse in the synovial fluid, creating a popping sound. This is the same phenomenon responsible for knuckle cracking.

- Tendon or Ligament Snapping: As tendons move over bony prominences during motion, they can momentarily snap or shift, producing a click. This is especially common with tight iliotibial (IT) bands or patellar tendons.

- Cartilage Irregularities: Over time, cartilage surfaces may develop minor wear or soft spots. As the femur and tibia glide over each other during squatting, these subtle imperfections can generate noise.

In most cases, these processes are painless and do not lead to degeneration. A 2015 study published in PLOS ONE found that nearly 99% of participants without knee pain still experienced crepitus during deep knee flexion. This suggests that joint noise alone is not a reliable indicator of pathology.

Differentiating Mechanics from Injury: Key Warning Signs

Not all knee clicking is created equal. While many instances are simply mechanical, others stem from structural problems that require intervention. The distinction lies in accompanying symptoms and functional limitations.

“Joint noise without pain is rarely a concern. But if clicking is associated with giving way, swelling, or sharp pain, it’s time to get evaluated.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Sports Medicine Physician

Below is a comparison table outlining the differences between normal joint mechanics and injury-related knee clicking:

| Feature | Normal Mechanics | Potential Injury |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Absent | Present, localized to joint line or behind kneecap |

| Swelling | None | Yes, especially after activity |

| Instability | No buckling or giving way | Frequent sensation of knee “giving out” |

| Frequency | Occasional, inconsistent | Consistent with every squat or movement |

| Range of Motion | Full and smooth | Stiffness or catching at certain angles |

| Response to Rest | No change needed; no discomfort | Symptoms improve with rest |

If your knee clicking matches the “Potential Injury” column, further assessment is warranted. Common conditions include meniscus tears, chondromalacia patellae, patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS), or early osteoarthritis.

Common Causes of Painful Knee Clicking During Squats

When knee noise is paired with discomfort, specific pathologies should be considered. Here are four of the most frequent culprits:

1. Meniscus Tears

The meniscus acts as a shock absorber between the femur and tibia. A tear—often caused by twisting under load—can create a flap of cartilage that catches during knee flexion. This leads to clicking, locking, or a feeling of something \"stuck\" in the joint. Athletes and older adults are particularly susceptible.

2. Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (Runner’s Knee)

This condition involves irritation of the cartilage beneath the kneecap. Misalignment or excessive pressure during squatting can cause the patella to track unevenly, resulting in grinding or clicking. Pain typically worsens with stairs, prolonged sitting, or deep squats.

3. Chondromalacia Patellae

A more advanced form of PFPS, chondromalacia refers to softening or breakdown of the articular cartilage on the underside of the patella. It produces a gritty or crunchy sensation during movement and is often diagnosed via MRI.

4. Loose Bodies or Cartilage Flaps

In rare cases, fragments of bone or cartilage break off inside the joint space. These “joint mice” can float freely and become lodged during motion, causing sudden clicking, pain, or mechanical blockage.

Step-by-Step Guide to Assessing and Addressing Knee Clicking

If you're unsure whether your knee clicking is harmless or problematic, follow this structured approach to self-evaluation and management:

- Monitor Symptoms Over 1–2 Weeks

Track when the clicking happens, whether it's painful, and if any swelling or stiffness develops. Keep a simple log after workouts or daily activities. - Perform a Functional Movement Screen

Stand in front of a mirror and perform 5 slow, controlled bodyweight squats. Watch for:- Knee wobbling inward (valgus collapse)

- Asymmetrical depth or movement

- Pain onset during descent or ascent

- Test Isometric Strength

Lie on your back and extend one leg. Press your heel into the floor while resisting with your hand just above the knee. Compare both sides. Weak quadriceps—especially the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO)—can contribute to poor patellar tracking. - Modify Your Training Temporarily

If pain is present, avoid deep squats, lunges, or high-impact exercises for 7–10 days. Replace them with step-ups, glute bridges, or seated leg extensions with light resistance. - Implement Mobility and Activation Drills

Add the following to your warm-up routine:- Quad and IT band foam rolling (2 minutes per side)

- Clamshells (2 sets of 15) to activate glutes

- Terminal knee extensions with a resistance band (3 sets of 10)

- Reintroduce Squats Gradually

After symptoms subside, return to squatting using a box or bench to limit depth. Focus on controlled tempo (3 seconds down, 1 second up) and proper alignment. - Seek Professional Evaluation if Needed

If clicking persists with pain beyond two weeks, consult a physical therapist or orthopedic specialist for imaging and gait analysis.

Real-World Example: A Powerlifter’s Recovery Journey

Mark, a 32-year-old competitive powerlifter, began noticing a sharp click in his right knee during back squats at around 60 degrees of flexion. Initially painless, the sound became increasingly frequent and was eventually accompanied by anterior knee pain and mild swelling after heavy sessions.

He followed the step-by-step guide above, logging his symptoms and modifying training. He discovered that his right knee consistently caved inward during squats—a sign of weak hip abductors. After two weeks of glute activation drills and reducing squat depth, his pain decreased significantly.

Still cautious, Mark visited a sports physiotherapist. An MRI ruled out meniscal tears but revealed early signs of chondromalacia. With targeted VMO strengthening, gait retraining, and improved squat technique, Mark returned to full training within eight weeks—without clicking or pain.

His case illustrates how early intervention and biomechanical awareness can prevent minor issues from becoming chronic injuries.

Prevention Checklist: Protect Your Knees Long-Term

To maintain healthy, silent knees during squatting and other movements, follow this actionable checklist:

- ✅ Warm up properly before lifting (include dynamic stretches and activation drills)

- ✅ Strengthen hip abductors and external rotators (glute medius, minimus)

- ✅ Maintain balanced quad-to-hamstring strength ratio

- ✅ Avoid rapid increases in training volume or intensity

- ✅ Use proper squat form: chest up, knees aligned with toes, neutral spine

- ✅ Incorporate unilateral exercises (e.g., split squats) to correct imbalances

- ✅ Listen to your body—don’t push through sharp or recurring pain

Frequently Asked Questions

Is knee clicking dangerous if there’s no pain?

No. Painless crepitus is extremely common and not linked to arthritis or joint damage. Research shows no increased risk of osteoarthritis in individuals who experience asymptomatic knee popping.

Can I keep squatting if my knee clicks?

Yes—if there’s no pain, swelling, or instability. However, consider evaluating your form and incorporating mobility work to ensure optimal joint mechanics. If symptoms develop, scale back and assess.

Should I get an MRI if my knee clicks?

Not unless you have pain, swelling, locking, or a history of trauma. Imaging is typically unnecessary for isolated clicking. Start with conservative management and consult a professional if symptoms persist.

Conclusion: Know Your Body, Trust the Signals

Your knees don’t need to be silent to be healthy—but they do need to be pain-free and functional. Clicking during squats is often just the sound of normal joint dynamics, not a warning siren. However, when noise comes with discomfort, weakness, or mechanical symptoms, it’s a signal to pause and investigate.

By understanding the mechanics behind knee sounds and recognizing red flags, you empower yourself to make informed decisions about training, recovery, and when to seek help. Small adjustments in technique, strength, and self-awareness can preserve joint health for decades.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?