Squatting is a fundamental movement pattern used in daily life and exercise, from sitting down to lifting weights. Many people notice a popping, cracking, or snapping sound in their knees during this motion. While often dismissed as normal, persistent or painful knee pops can raise concerns. Understanding whether your knee noise is benign or a sign of underlying damage is essential for long-term joint health.

The medical term for joint noises like popping or cracking is *crepitus*. It’s common in knees, shoulders, and other joints. But not all crepitus is created equal. Some types are completely harmless; others may point to cartilage wear, ligament strain, or early osteoarthritis. This article breaks down the science behind knee popping, identifies risk factors, and provides actionable guidance on when to monitor, modify, or seek treatment.

What Causes Knee Popping During Squats?

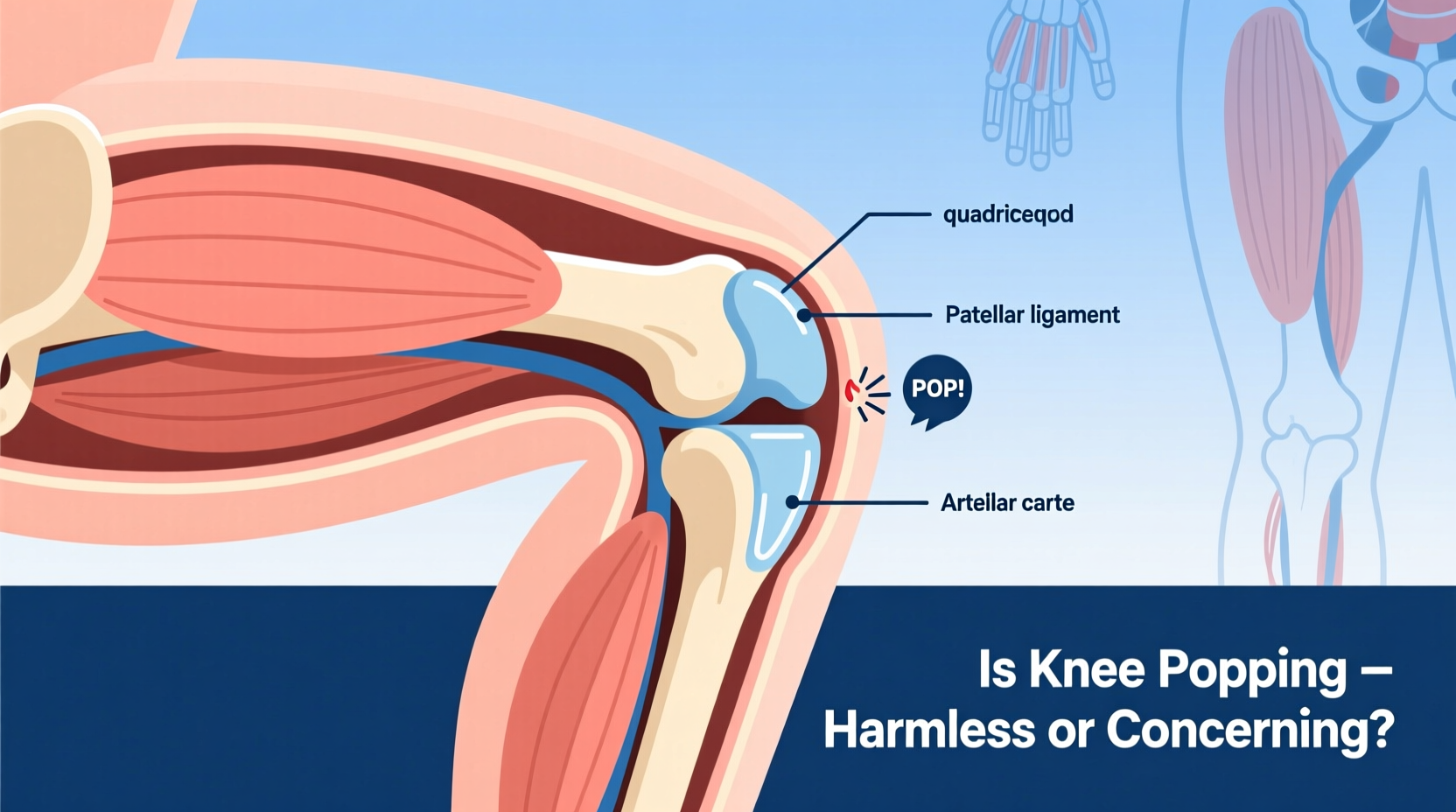

Knee popping occurs due to physical changes within the joint space or surrounding soft tissues. The most frequent causes are mechanical and physiological—meaning they stem from how the joint moves and interacts with air, fluid, and tissue.

1. Cavitation (Gas Release)

The most common reason for a painless pop is the release of gas from the synovial fluid inside the joint. When you bend your knee into a squat, pressure shifts within the joint capsule. This can cause nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon dioxide dissolved in the synovial fluid to form tiny bubbles that rapidly collapse—a process known as cavitation. The resulting “pop” is similar to what happens when you crack your knuckles. It’s typically harmless and doesn’t require intervention.

2. Tendon or Ligament Snapping

Tendons and ligaments glide over bony structures as the knee flexes and extends. If a tendon—such as the iliotibial (IT) band or patellar tendon—is slightly tight or misaligned, it may snap over a bony prominence like the femoral condyle or kneecap. This produces an audible pop or click, especially at certain angles during a squat. This type of noise is usually repetitive and predictable but only becomes problematic if it causes discomfort or inflammation over time.

3. Cartilage Irregularities

Articular cartilage covers the ends of bones in the knee joint, allowing smooth movement. Over time, wear, injury, or degenerative conditions like chondromalacia patellae (softening of the kneecap cartilage) can create rough spots. As the joint moves, these uneven surfaces may produce grinding or popping sensations. Unlike gas-related pops, cartilage-based crepitus is often accompanied by a gritty feeling and may worsen with activity.

4. Meniscus Tears

The menisci are C-shaped pieces of cartilage that cushion the knee. A tear—often from twisting motions or age-related degeneration—can cause a flap of tissue to catch between the femur and tibia during squatting. This frequently results in a distinct, sometimes painful pop, often followed by swelling, locking, or a sensation of instability.

Harmless vs. Concerning: How to Tell the Difference

Distinguishing between normal joint noise and a symptom of injury requires attention to context. Consider three key factors: pain, swelling, and function.

A 2021 study published in the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy found that nearly 70% of asymptomatic adults report occasional knee crepitus during squats, particularly under load. However, only those with concurrent symptoms showed evidence of structural pathology on imaging.

“Joint noise alone isn’t diagnostic. We care about the combination of sound, pain, and mechanical symptoms like catching or giving way.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Sports Medicine Physician

Use the following checklist to evaluate your situation:

✅ Likely Harmless If:

- The pop occurs once per session and doesn’t repeat consistently

- No pain, swelling, or stiffness follows the noise

- You can continue squatting without hesitation or weakness

- The sound happens only at certain ranges of motion (e.g., deep squat bottom)

- You have no history of knee injury or arthritis

⚠️ Potentially Concerning If:

- Pain accompanies the pop, especially sharp or localized pain

- Swelling develops hours after activity

- The knee feels unstable, locks, or “gives out”

- Popping increases in frequency or becomes louder

- You’ve had prior knee trauma (e.g., ACL injury, dislocation)

Common Risk Factors for Problematic Knee Popping

Certain lifestyle and biomechanical factors increase the likelihood that knee popping signals trouble. Identifying and modifying these can reduce progression to more serious conditions.

| Risk Factor | Why It Matters | How to Address |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Squat Form | Valgus collapse (knees caving inward), excessive forward lean, or heel lift increases shear forces on the joint. | Record your squats, work with a coach, strengthen glutes and hips. |

| Muscle Imbalances | Weak quadriceps, tight hamstrings, or underactive glutes alter patellar tracking. | Include single-leg exercises, foam rolling, and mobility drills. |

| Previous Knee Injury | Past sprains, meniscus tears, or surgeries predispose to recurrent issues. | Rehab fully before returning to heavy loading; consider maintenance PT. |

| Overuse or Rapid Load Increases | Sudden jumps in training volume stress unprepared tissues. | Follow the 10% rule: increase weight or reps by no more than 10% weekly. |

| Age-Related Wear | Natural cartilage thinning begins in the 30s–40s, increasing crepitus risk. | Focus on low-impact strength training and joint nutrition (e.g., collagen, omega-3s). |

Mini Case Study: The Weekend Athlete with Recurring Knee Pops

Mark, a 38-year-old recreational CrossFitter, began noticing a loud pop in his right knee every time he reached the bottom of a back squat. Initially painless, the sound became sharper over six weeks, eventually accompanied by a twinge behind the kneecap. He also felt mild swelling after workouts.

After consulting a physical therapist, Mark learned his hip external rotators were weak, causing his right knee to drift inward during descent. This altered patellar tracking, creating friction and irritation under the kneecap. An MRI ruled out meniscus tears, confirming early-stage chondromalacia.

His rehab plan included:

- Temporarily reducing squat depth and load

- Daily clamshells, banded walks, and step-downs

- Soft tissue work on the IT band and quads

- Gait retraining using video feedback

Step-by-Step Guide to Assessing and Managing Knee Pops

If you’re experiencing knee noise during squats, follow this structured approach to determine next steps:

- Document the Details

Note when the pop occurs (e.g., descent, ascent), whether it’s reproducible, and if pain or swelling follows. Use a journal or voice memo app. - Perform a Self-Test

Do 10 bodyweight squats slowly. Repeat with feet wider and toes slightly out. Does the pop change? If yes, it may be biomechanical—not structural. - Check for Swelling or Tenderness

Feel around the kneecap, joint line, and behind the knee. Swelling indicates inflammation; tenderness may pinpoint injury location. - Assess Strength and Mobility

Try single-leg squats or step-ups. Weakness or wobbling suggests muscular deficits. Tight hamstrings or calves can also affect knee alignment. - Modify Activity Temporarily

If pain is present, reduce squat depth or switch to leg press or split squats. Avoid deep knee bends until symptoms resolve. - Consult a Professional

If symptoms persist beyond 2–3 weeks despite rest and modification, see a physical therapist or orthopedic specialist. Imaging may be needed.

When to See a Doctor

Most knee pops don’t require medical attention. However, certain red flags warrant prompt evaluation:

- Locking or catching: Inability to fully straighten the knee suggests a meniscal tear or loose body.

- Instability: Feeling like the knee will give out may indicate ligament damage (e.g., ACL).

- Progressive swelling: Fluid accumulation points to internal bleeding or synovitis.

- Night pain or rest pain: Pain at night or when inactive is more concerning than activity-related discomfort.

- History of trauma: If the popping started after a fall, twist, or impact, get it checked even if pain subsides.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it bad to squat if my knee pops?

Not necessarily. If the pop is pain-free and doesn’t affect performance, continuing to squat with proper form is generally safe. However, avoid pushing through pain or increasing load if the noise becomes more frequent or uncomfortable.

Can strengthening exercises stop knee popping?

Yes, especially if the cause is muscular imbalance or poor tracking. Strengthening the glutes, quadriceps (particularly the vastus medialis obliquus), and hip stabilizers improves alignment and reduces abnormal joint stress that leads to noise.

Does knee popping lead to arthritis?

No direct evidence shows that painless crepitus causes osteoarthritis. However, if popping is due to existing cartilage damage, the underlying condition may progress over time. The sound itself isn’t harmful, but the cause matters.

Conclusion: Listen to Your Body, Not Just the Sound

Your knee might pop for entirely normal reasons—gas release, tendon movement, or minor cartilage texture changes. But when popping comes with pain, swelling, or dysfunction, it’s your body’s way of signaling imbalance or injury. Ignoring these cues can lead to chronic issues, reduced mobility, and longer recovery times.

Taking proactive steps—assessing your movement, correcting imbalances, and seeking expert advice when needed—ensures your knees remain strong and resilient. Whether you're a lifter, runner, or simply someone who wants to move freely, understanding the story behind the pop empowers smarter choices today for healthier joints tomorrow.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?