It’s a familiar scene: you take a bite of a fiery curry or a plate of wasabi-laced sushi, and within seconds, your nose starts to drip uncontrollably. You’re not crying from emotion—your eyes may be watering, but the real issue is the sudden, persistent nasal discharge that seems triggered exclusively by spicy foods. This phenomenon affects millions of people worldwide, yet many don’t understand why it happens. The answer lies in human physiology, nerve signaling, and the clever ways our body responds to chemical irritants. This article explores the biological mechanisms behind spice-induced rhinorrhea (runny nose), identifies which ingredients are most likely to cause it, and offers practical advice for managing it.

The Role of TRPV1 Receptors in Nasal Response

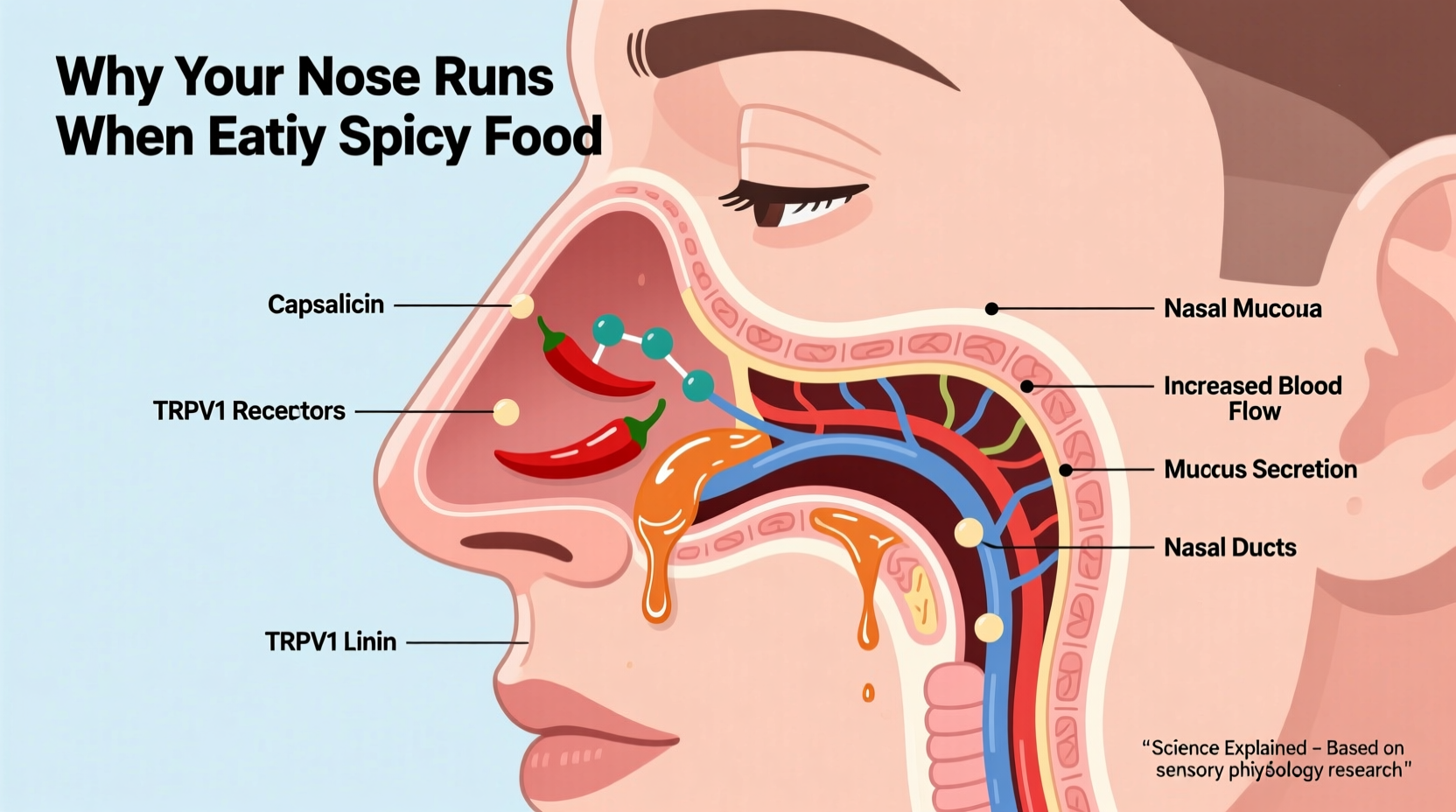

At the heart of this reaction is a group of sensory receptors known as transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1). These receptors are primarily located in the mucous membranes of the mouth, throat, and nasal passages. They evolved to detect heat, acidity, and certain chemical compounds—essentially acting as the body’s warning system for potentially harmful stimuli.

When you consume capsaicin—the active compound in chili peppers—these TRPV1 receptors are activated. Capsaicin mimics the sensation of heat, tricking your nervous system into thinking your mouth is being burned. This false alarm triggers a cascade of physiological responses, including increased saliva production, sweating, and notably, nasal discharge.

The signal from the TRPV1 receptors travels via the trigeminal nerve, a major cranial nerve responsible for facial sensation. Once activated, the trigeminal nerve communicates with the autonomic nervous system, which controls involuntary functions like mucus secretion. As a result, the blood vessels in the nasal lining dilate, and the glands produce more mucus in an attempt to flush out the perceived irritant—even though no actual physical threat exists.

“Capsaicin doesn’t damage tissue, but it activates pain and temperature pathways so effectively that the body responds as if it's under attack.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Neurophysiologist at Boston Medical Research Institute

Spicy Compounds That Trigger a Runny Nose

Not all spicy foods work the same way. Different ingredients activate distinct neural pathways, leading to similar but subtly different reactions. Below is a breakdown of the most common culprits:

| Compound | Found In | Receptor Targeted | Nasal Response Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capsaicin | Chili peppers (jalapeños, habaneros, cayenne) | TRPV1 | High – strong mucus production |

| Allyl isothiocyanate | Wasabi, horseradish, mustard | TRPA1 | Very High – rapid, sharp nasal drip |

| Piperine | Black pepper | TRPV1 (mild) | Moderate – mild irritation |

| Gingerol | Fresh ginger | TRPV1 and others | Low to Moderate – warming sensation, slight drip |

While capsaicin is the most widely recognized trigger, allyl isothiocyanate—found in wasabi—is particularly potent at inducing a fast, intense nasal response. Unlike capsaicin, which produces a slow-building burn, wasabi acts almost instantly, often causing a sharp, upward sensation into the sinuses followed by immediate mucus flow. This is because TRPA1 receptors are highly sensitive to volatile compounds that easily travel through the air and up the back of the nasal cavity during chewing.

Why Doesn’t My Nose Run with Other Strong Flavors?

You might wonder why extremely sour, bitter, or salty foods don’t provoke the same reaction. The answer lies in the specificity of nerve activation. Taste receptors on the tongue (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, umami) are separate from the chemesthetic receptors like TRPV1 and TRPA1, which respond to chemical irritants rather than taste.

For example, lemon juice may make your eyes water due to salivation reflexes, but it doesn’t activate the trigeminal nerve pathway that leads to nasal secretion. Similarly, alcohol can create a burning sensation, but unless it contains spicy additives, it rarely causes prolonged rhinorrhea. It’s the combination of volatility (for airborne compounds like wasabi) and receptor targeting that makes certain spices uniquely effective at triggering a runny nose.

This also explains why drinking hot coffee doesn’t usually cause the same effect—even though it’s physically hot. Real thermal heat activates TRPV1 too, but without the sustained chemical binding that capsaicin provides, the response is shorter and less intense.

Managing the Drip: Practical Strategies

While spice-induced rhinorrhea is harmless, it can be socially awkward or uncomfortable, especially during meals. Fortunately, several strategies can reduce or prevent the symptoms without sacrificing flavor.

Step-by-Step Guide to Minimizing Nasal Drip When Eating Spicy Foods

- Choose lower-heat alternatives: Substitute fresh chilies with smoked paprika or sweet peppers for color and depth without intense capsaicin.

- Pair with dairy: Consume yogurt, milk, or cheese alongside spicy dishes. Casein in dairy helps break down capsaicin molecules, reducing receptor activation.

- Avoid volatile spices on empty stomach: Eating a small carbohydrate-rich snack before diving into wasabi prevents rapid absorption and exaggerated responses.

- Sip cold fluids: Cold water or milk can soothe irritated nerves and wash away residual compounds.

- Breathe through your mouth: During consumption, inhaling through the mouth reduces airflow through the nasal passages, limiting the transport of volatile irritants like allyl isothiocyanate.

- Use nasal saline afterward: If your nose remains runny post-meal, a gentle saline rinse can clear excess mucus and calm irritated tissues.

Checklist: How to Enjoy Spicy Food Without the Drip

- ✅ Eat dairy before or with spicy meals

- ✅ Chew slowly to minimize vapor release

- ✅ Keep a napkin or tissue handy

- ✅ Avoid combining multiple spicy agents (e.g., chili + wasabi)

- ✅ Stay hydrated with cool liquids

- ✅ Consider desensitization over time (regular exposure may reduce sensitivity)

Real-Life Example: A Sushi Lover’s Dilemma

Tamara, a 34-year-old graphic designer from Portland, loves Japanese cuisine but dreads the embarrassment of her nose running every time she eats wasabi. “I’ll be at a business lunch, trying to look professional, and one dab of wasabi and I’m sniffling nonstop,” she says. After consulting an allergist, she learned she wasn’t allergic—just highly reactive to volatile compounds.

She began experimenting with solutions: mixing wasabi into soy sauce to dilute it, pairing rolls with miso soup and edamame first, and always keeping a travel-sized saline spray in her bag. Over time, she noticed her reactions became less severe. “I still get a little drip, but now I’m prepared. And honestly, I think people relate—it’s kind of a shared experience among spice lovers.”

Tamara’s case illustrates that while the response is physiological, behavior and preparation can significantly influence comfort and confidence when enjoying bold flavors.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is a runny nose from spicy food a sign of allergy?

No. True food allergies involve the immune system and typically cause symptoms like hives, swelling, or difficulty breathing. A runny nose from spicy food is a neurological and physiological reflex, not an allergic reaction. However, if you experience wheezing, throat tightness, or rash, consult a doctor to rule out actual allergy or sensitivity.

Can children experience this too?

Yes. Children have the same TRP receptors and can experience spice-induced rhinorrhea. However, their smaller nasal passages and less developed tolerance may make the effect more pronounced. Introduce spicy foods gradually and monitor for discomfort.

Will I become less sensitive over time?

Many people do. Regular exposure to capsaicin can lead to temporary desensitization of TRPV1 receptors, meaning the same amount of spice produces a weaker response over time. This is why frequent consumers of spicy food often tolerate high heat levels with minimal nasal symptoms.

Conclusion: Embrace the Drip, Understand the Science

Your nose running when you eat spicy food isn’t a flaw—it’s a testament to the sophistication of your nervous system. What feels like an inconvenience is actually your body’s intelligent effort to protect itself from perceived threats, even if those threats come in the form of a delicious Thai red curry. By understanding the role of TRP receptors, recognizing which compounds trigger the strongest responses, and applying simple dietary and behavioral adjustments, you can continue enjoying bold flavors with greater comfort and control.

Next time you reach for that extra-hot salsa or dollop of wasabi, remember: the drip isn’t a weakness. It’s biology in action. And with the right knowledge, you can savor the heat—without losing your composure.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?