It’s a familiar frustration: you step into an elevator, your call is going strong, and within seconds—silence. The connection cuts out, texts fail to send, and even loading a simple webpage becomes impossible. This isn’t a flaw in your phone or carrier—it’s physics. Elevators are notorious for killing mobile signals, and the reasons lie in the way radio waves interact with metal enclosures, building design, and electromagnetic shielding. Understanding the science behind this phenomenon not only explains the inconvenience but also reveals how wireless communication works—and fails—in enclosed spaces.

The Science of Radio Waves and Signal Propagation

Mobile phones rely on radio frequency (RF) signals to communicate with cell towers. These signals are a form of electromagnetic radiation, typically in the range of 700 MHz to 2.5 GHz, depending on the network (4G LTE, 5G, etc.). Like all electromagnetic waves, they travel through space and can penetrate certain materials, but their ability to do so depends on wavelength, material density, and structural geometry.

When a phone sends or receives data, it transmits RF energy that must travel unimpeded—or at least with minimal obstruction—to a nearby cell tower. However, obstacles such as concrete walls, metal framing, and especially fully enclosed metal chambers like elevators disrupt this flow. The denser and more conductive the material, the more likely it is to reflect, absorb, or scatter incoming signals.

In open environments, signals propagate via line-of-sight, reflection, diffraction, and scattering. But inside a steel-walled elevator shaft, none of these mechanisms work effectively. The result? A sudden and often total loss of connectivity.

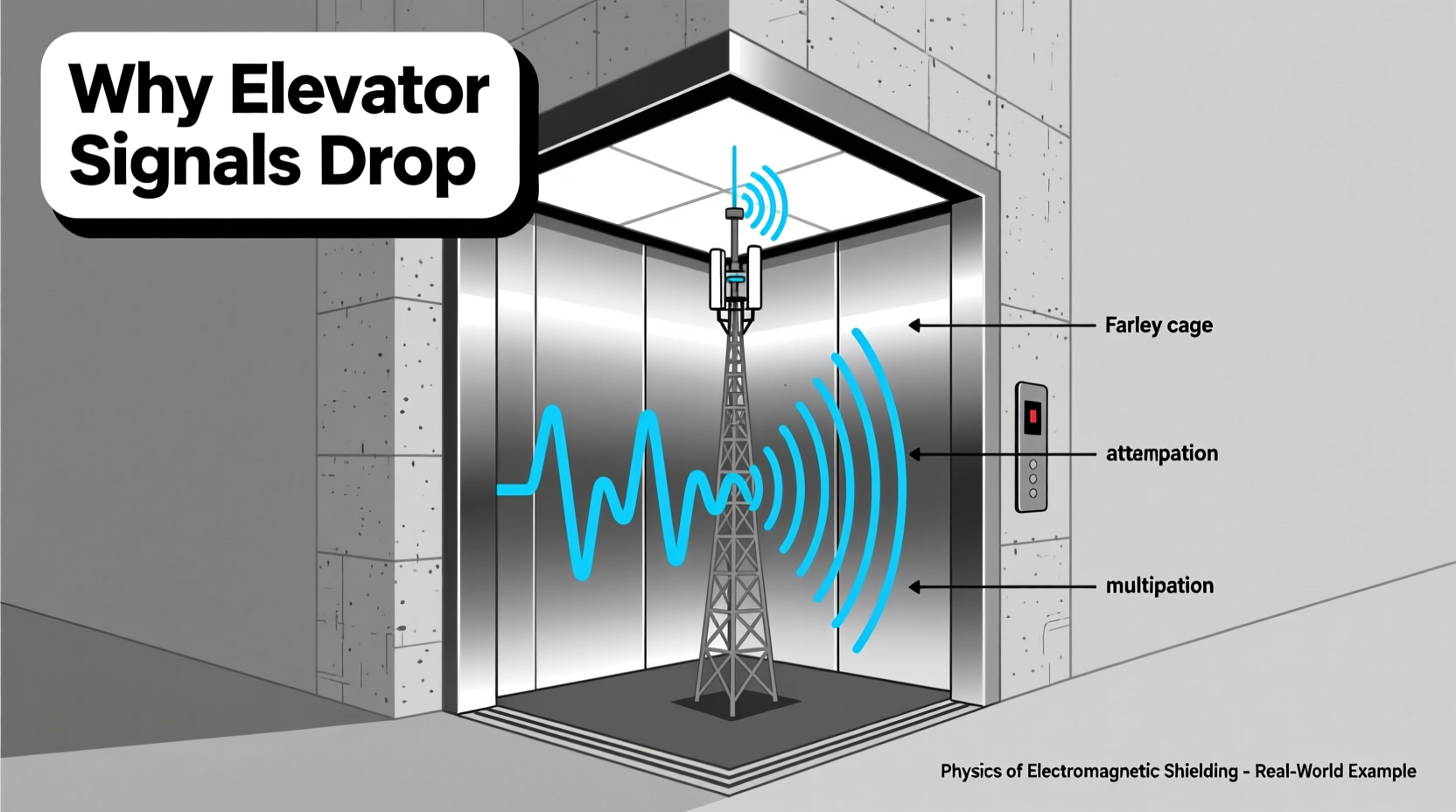

Why Elevators Act Like Faraday Cages

The primary reason for signal loss in elevators is their construction. Most elevator cabs are made of thick steel panels, forming a near-perfect enclosure. This structure functions as a Faraday cage—a concept first demonstrated by scientist Michael Faraday in 1836.

A Faraday cage is an enclosure made of conductive material (like copper or steel) that blocks external electric fields. When external electromagnetic waves hit the surface of the cage, the free electrons in the metal rearrange themselves to cancel the field's effect inside the enclosure. In simpler terms: the metal shell absorbs and redistributes the incoming RF energy around the outside, leaving the interior shielded.

Elevators weren't designed to be Faraday cages, but their metal construction unintentionally creates one. The continuous conductive surface prevents most radio frequencies from penetrating, effectively isolating anything inside—including your smartphone—from cellular networks, Wi-Fi, and sometimes even emergency radio bands.

“Any enclosed metallic structure will attenuate electromagnetic signals. Elevators are essentially moving metal boxes—ideal conditions for signal blockage.” — Dr. Lena Patel, RF Engineer and Telecommunications Researcher

Building Materials and Structural Interference

Even if the elevator cab itself weren’t problematic, the surrounding infrastructure worsens the issue. Elevator shafts are typically built within the core of high-rise buildings, surrounded by dense concrete, rebar, and mechanical systems—all of which further degrade signal strength.

- Concrete and rebar: Reinforced concrete contains steel mesh that acts as a partial Faraday cage. Thick walls between the exterior and the building’s interior significantly weaken incoming signals.

- Basement locations: Many elevators start in underground parking or utility levels, where signals are already weak due to lack of line-of-sight to towers.

- Multiple obstructions: As the elevator ascends or descends, it passes through multiple floors, each adding layers of interference. Temporary signal recovery may occur near floor openings, but it’s often too brief to re-establish a stable connection.

Moreover, modern energy-efficient building designs use low-emissivity (low-E) glass and insulated metal panels, which also reflect or absorb RF waves. While great for climate control, these materials are detrimental to indoor cellular coverage.

Solutions and Workarounds: Staying Connected

While physics makes elevators natural dead zones, technology offers ways to mitigate the problem—both for individuals and building managers.

Distributed Antenna Systems (DAS)

Many commercial and high-rise residential buildings install Distributed Antenna Systems (DAS). These are networks of small antennas placed throughout a building, including elevator shafts, that connect to a central signal source. DAS units receive outdoor cellular signals via rooftop antennas, amplify them, and rebroadcast them indoors. In elevators, a dedicated antenna mounted inside the shaft ensures continuous coverage as the cab moves.

Femtocells and Microcells

Smaller-scale solutions include femtocells—miniature base stations provided by carriers that use broadband internet to route calls and data. While typically used in homes, they can be deployed in lobbies or maintenance rooms to boost local service, though they rarely cover moving elevators directly.

Wi-Fi Calling

If the building has strong Wi-Fi coverage extending into elevator lobbies or shafts (via repeaters), enabling Wi-Fi calling on your phone can maintain voice and text functionality. However, most elevators don’t have internal Wi-Fi access points, so this only helps if the connection was established just before entry and remains active briefly.

Step-by-Step Guide to Improving Personal Connectivity Around Elevators

While you can’t retrofit an elevator yourself, there are practical steps you can take to minimize disruption:

- Check carrier coverage maps: Before moving into or frequenting a building, verify your provider’s indoor performance in high-rises.

- Enable Wi-Fi calling: Go to your phone settings (Settings > Phone > Wi-Fi Calling) and turn it on. Test it in areas with known poor reception.

- Use messaging apps with offline sync: Apps like WhatsApp or iMessage queue messages when disconnected and send them once reconnected.

- Inform contacts: Let people know you’re entering an area with spotty service, especially during important calls.

- Advocate for better infrastructure: If you manage or live in a building, suggest installing a DAS or working with carriers to improve indoor coverage.

Real-World Example: The Case of Metro Tower

Metro Tower, a 32-story mixed-use building in downtown Chicago, received consistent complaints about dropped calls in elevators. Tenants reported failed video conferences and lost emergency alerts while traveling between floors. A site survey revealed that the steel-clad elevators and concrete core completely blocked all major carrier bands.

The building management partnered with a telecommunications firm to install a multi-carrier DAS system. Antennas were mounted every three floors along the elevator shaft, connected via fiber to a central hub. After implementation, signal strength inside elevators improved from -115 dBm (undetectable) to -75 dBm (excellent), restoring full voice and data services.

The project cost $85,000 but increased tenant satisfaction and property value. It also met new city safety codes requiring reliable communication in vertical transit zones.

Do’s and Don’ts: Managing Expectations in Low-Signal Zones

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Enable Wi-Fi calling if available | Assume your phone will work normally in any elevator |

| Send a heads-up message before entering | Start critical calls once inside the cab |

| Use offline modes in navigation or productivity apps | Rely solely on cellular data in basements or cores |

| Report persistent issues to building management | Blame your carrier without checking building-specific factors |

FAQ: Common Questions About Elevator Signal Loss

Why does my phone sometimes regain signal between floors?

As the elevator passes floor landings, small gaps between the cab and shaft allow brief signal leakage. If an external antenna is nearby or the wall material is less dense at that level, temporary reception may occur. However, this is inconsistent and usually lasts only seconds.

Can 5G signals penetrate elevators better than 4G?

No—ironically, higher-frequency 5G bands (especially mmWave) are worse at penetration than lower-band 4G. While low-band 5G (600–700 MHz) travels farther and through walls slightly better, it still cannot overcome the shielding effect of a fully enclosed metal cabin.

Are some elevators designed to allow signal transmission?

Yes. Modern smart buildings increasingly incorporate RF-transparent materials or embedded antennas in elevator designs. Some use conductive gaskets with grounding paths to maintain structural integrity while allowing selective signal passage. However, these are exceptions, not the norm.

Conclusion: Embracing the Limits of Wireless Communication

The disappearance of phone signal in elevators is not a malfunction—it’s a predictable outcome of physics meeting engineering. Metal enclosures, reinforced structures, and the nature of radio wave propagation create unavoidable dead zones. But awareness transforms frustration into preparedness.

By understanding the principles behind signal loss, users can adapt their communication habits, leverage available technologies like Wi-Fi calling, and advocate for better infrastructure. For building designers and urban planners, integrating connectivity into vertical transportation is no longer optional—it’s a necessity for safety, productivity, and modern living.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?