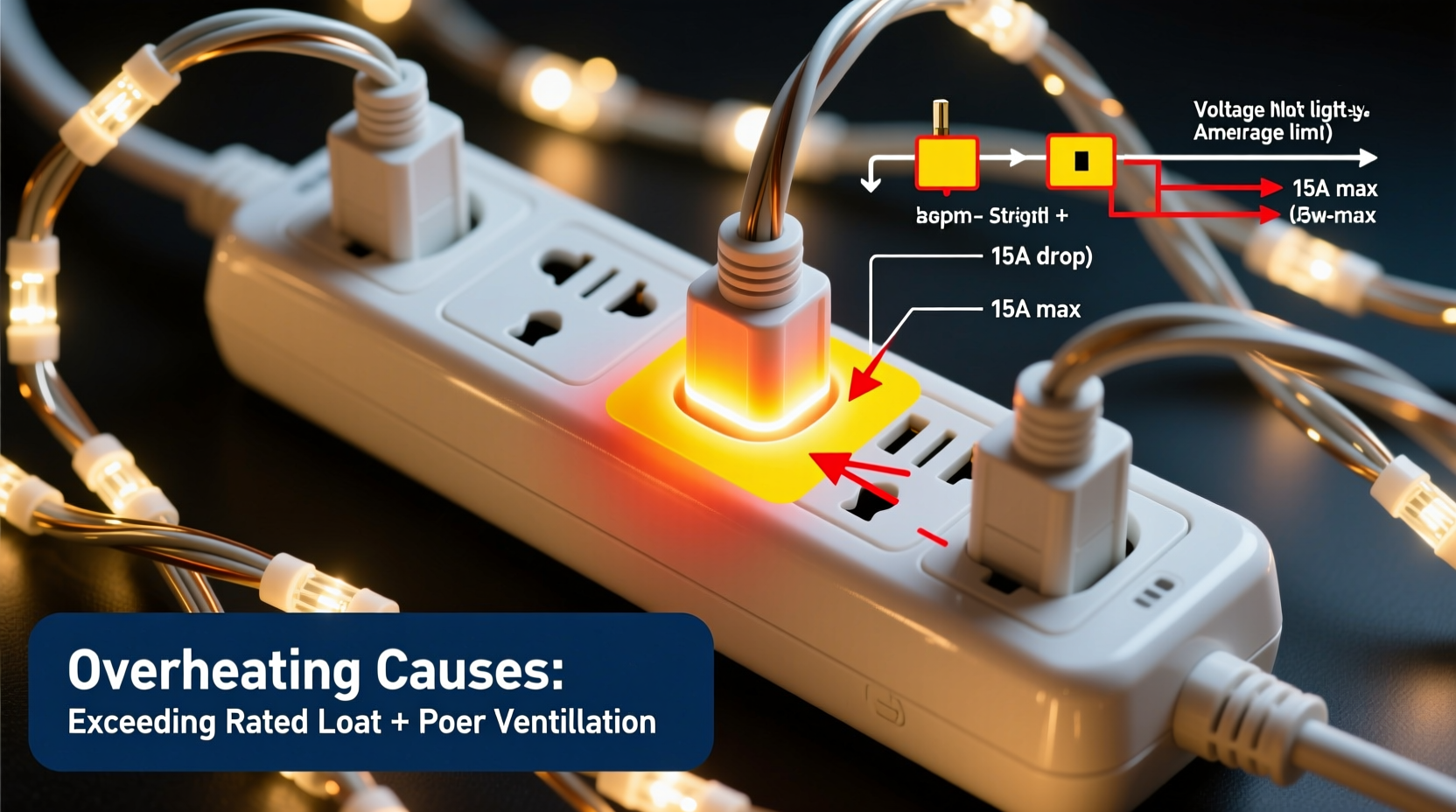

It’s a familiar scene: holiday lights strung across the porch, draped over mantels, wrapped around trees—each strand plugged into a single power strip. Then, halfway through December, you notice it: the plastic housing feels warm to the touch. Not just warm—distinctly hot. Maybe even emitting a faint, acrid odor. Your instinct says “it’s fine—it’s just lights,” but your nervous system whispers something else. That warmth isn’t benign. It’s physics in action—and often, a quiet warning sign of electrical stress that could escalate into melted insulation, tripped breakers, or worse.

This isn’t about faulty cheer. It’s about fundamental electrical principles interacting with everyday consumer products. Modern LED light strands draw less current than incandescent ones—but when you daisy-chain six, eight, or twelve of them into one outlet via a power strip, cumulative load, internal resistance, poor contact points, and inadequate thermal design converge. The result? Heat. And heat is electricity’s most visible symptom of inefficiency—and its most common precursor to failure.

How Power Strips Convert Electrical Energy Into Heat

A power strip isn’t a passive conduit. It contains copper conductors, internal wiring, circuitry (in surge-protected models), and mechanical contacts—all with inherent resistance. When current flows, energy converts to heat according to Joule’s Law: Q = I² × R × t, where Q is heat energy, I is current in amperes, R is resistance in ohms, and t is time. Crucially, heat generation scales with the *square* of current. Double the current, and heat quadruples.

Consider a typical 15-amp household circuit. A standard UL-listed power strip rated for 15 amps may have internal wiring as thin as 16–18 AWG (American Wire Gauge) and contact points with micro-gaps or oxidation. Even at 80% load—12 amps—the resistance across those contacts can generate 3–5 watts of heat per connection point. Multiply that across four outlets and two internal junctions, and localized temperatures easily exceed 60°C (140°F)—well above safe surface limits for PVC housings.

That’s why a power strip warming up under load isn’t necessarily alarming—but sustained heat above 50°C (122°F), discoloration, or a burning smell means resistance has increased beyond safe thresholds. This often stems not from the lights themselves, but from how they’re connected.

The Real Culprits: Why “Just Lights” Aren’t the Whole Story

Most people assume the problem lies with the light strands. In reality, the lights are usually within spec—but their interaction with the power strip creates the hazard. Here are the five most common contributors:

- Daisy-chaining power strips: Plugging one strip into another multiplies resistance and reduces effective current capacity. UL prohibits this outright—but it remains widespread.

- Overloading outlet banks: Many power strips list “15A max” on the label—but that rating assumes ideal conditions: short cord length, ambient temperature ≤25°C, no other loads, and perfect contact integrity. Real-world use rarely meets those conditions.

- Poor contact resistance: Each plug insertion introduces microscopic gaps. Over time, repeated plugging/unplugging, dust accumulation, or low-quality brass contacts increase resistance. A contact resistance of just 0.1 Ω at 10 amps generates 10 watts of heat—enough to soften plastic near the socket.

- Undersized internal wiring: Budget power strips often use 18 AWG wire internally—even though the National Electrical Code (NEC) recommends 14 AWG for 15-amp circuits over any appreciable distance. Thinner wire = higher resistance = more heat.

- Enclosed or insulated placement: Tucking a loaded power strip behind furniture, under rugs, or inside decorative boxes traps heat. Thermal buildup accelerates resistance rise, creating a dangerous feedback loop.

When Warmth Becomes a Warning: Recognizing Dangerous Heat Levels

Not all warmth indicates danger—but distinguishing safe operation from hazardous conditions requires objective benchmarks. Use an infrared thermometer (or carefully test with the back of your hand) to assess surface temperature:

| Surface Temperature | Perceived Sensation | Risk Assessment | Action Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 40°C (104°F) | Warm, comfortable to hold | Normal operation | None—monitor periodically |

| 40–50°C (104–122°F) | Noticeably warm; uncomfortable to hold >3 sec | Elevated load; possible early resistance buildup | Unplug non-essential devices; verify total load |

| 50–60°C (122–140°F) | Hot; brief contact only | Unsafe for prolonged use; risk of insulation degradation | Immediately unplug all loads; inspect for damage; replace strip |

| > 60°C (140°F) | Painful to touch; may cause minor burns | Critical hazard; potential for melting, arcing, fire | Stop use permanently; discard unit; check circuit breaker for signs of overload |

Note: Temperatures above 60°C can initiate thermal runaway in PVC housings—where rising temperature further increases resistance, which generates more heat, accelerating failure. This process can occur in minutes under sustained overload.

Real-World Example: The Porch Light Cascade Failure

In late November 2023, a homeowner in Portland, Oregon, connected nine 25-foot LED light strands (each rated 0.07A, totaling 0.63A) to a $12 “heavy-duty” power strip labeled “15A.” He also plugged in a small outdoor fan (1.2A) and a string of solar-charged pathway lights (0.1A). Total measured load: 1.94A—well below the 15A rating.

Yet the strip heated to 58°C within 90 minutes. Investigation revealed three issues: First, the strip had been stored in a garage for two winters—causing micro-corrosion on contacts. Second, it was mounted vertically behind a wooden planter box, blocking airflow. Third, the manufacturer used 18 AWG internal wiring with solder joints prone to cold-flow deformation under thermal cycling.

When tested with a calibrated clamp meter, contact resistance at Outlet #3 measured 0.18 Ω—nearly triple the safe limit of 0.06 Ω for that current level. That single outlet alone generated 6.3 watts of heat, concentrated in a 1 cm² area. Within 4 hours, the adjacent outlet housing deformed, exposing live terminals. Fortunately, the homeowner smelled ozone and unplugged it before failure.

This case illustrates a critical truth: Load calculations alone don’t guarantee safety. Environmental factors, component aging, and manufacturing quality determine real-world performance.

Expert Insight: What Electrical Engineers Say About Holiday Lighting Loads

“The biggest misconception is that ‘low-wattage LEDs’ mean ‘no thermal risk.’ But power strips fail not from absolute wattage—but from localized resistive heating at connection points. A 10-watt LED strand drawing 0.08A can generate more contact heat than a 60-watt incandescent if the plug contacts are oxidized or undersized. Always derate manufacturer ratings by 30% for continuous holiday use—and never exceed 80% of the circuit’s breaker rating.”

— Dr. Lena Torres, PE, Senior Electrical Safety Engineer, Underwriters Laboratories (UL)

Dr. Torres’ guidance aligns with UL 1363 standards, which require power strips to withstand 100% rated load for 100 hours without exceeding 50°C surface temperature. Yet many budget units sold online skip full UL certification—relying instead on “UL-recognized components” without system-level validation. That gap explains why identical-looking strips perform radically differently under identical loads.

Step-by-Step: Safely Powering Multiple Light Strands Without Overheating

- Calculate total amperage: Add the amp ratings (not wattage) of every device. Find amps by dividing watts by voltage (e.g., 48W ÷ 120V = 0.4A). Use the label on each light strand—don’t rely on generic estimates.

- Verify circuit capacity: Locate your home’s breaker panel. Identify the circuit powering your outlet. Most lighting circuits are 15A; kitchen/outdoor circuits may be 20A. Never exceed 80% of that rating (12A for 15A circuit).

- Select the right power strip: Choose one with: (a) UL 1363 certification (look for the full UL mark—not just “UL Listed”); (b) 14 AWG internal wiring; (c) individual outlet circuit breakers (not just one master breaker); (d) metal housing or high-temp thermoplastic.

- Optimize physical setup: Mount the strip vertically on a wall or stud—never behind furniture or under rugs. Ensure ≥2 inches of clearance on all sides. Use cord organizers—not tape—to manage excess cable.

- Test and monitor: After setup, measure surface temperature with an IR thermometer after 15, 30, and 60 minutes. If it exceeds 45°C, reduce load immediately. Re-test weekly during extended use.

Do’s and Don’ts for Safe Holiday Lighting Power Management

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Use a dedicated outdoor-rated GFCI outlet for exterior strands | Plug indoor-rated strips outdoors—even under cover |

| Replace power strips every 3 years, even if undamaged | Use strips with cracked housings, bent prongs, or loose outlets |

| Label each outlet on the strip with its connected load | Plug transformers, motors, or heating devices into the same strip as lights |

| Install a whole-house surge protector in addition to strip-based protection | Assume “surge protected” means “overload protected” |

| Unplug lights overnight or when away for >8 hours | Leave strands powered continuously for weeks without inspection |

FAQ: Addressing Common Concerns

Can I safely run 12 LED light strands on one power strip?

Yes—if total amperage stays below 12A (for a 15A circuit) and the strip is UL 1363 certified with 14 AWG wiring. However, most LED strands draw 0.04–0.08A each, so 12 strands equal ~0.5–1.0A—well within limits. The real risk comes from adding other devices (fans, inflatables, controllers) or using low-quality strips. Always measure actual load—not assume.

Why does my new power strip get hotter than my old one—even with the same lights?

Newer budget strips often use thinner internal wiring (18 AWG vs. older 16 AWG), cheaper contact materials (zinc alloy vs. brass), and tighter housing designs that trap heat. Older units may have been built to stricter pre-2010 manufacturing standards—or simply benefited from heavier copper content. Age isn’t always the enemy; cost-cutting is.

Is it safer to plug lights directly into wall outlets instead of using a power strip?

Yes—if you have enough wall outlets spaced appropriately. Wall outlets connect directly to 14 AWG or 12 AWG branch circuit wiring, with robust screw-terminal connections. Power strips add two extra contact points per device (plug + socket) and internal wiring—all potential heat sources. For permanent or high-load setups, dedicated outlets are inherently safer.

Conclusion

A warm power strip isn’t a seasonal quirk—it’s physics delivering urgent feedback. That subtle heat is resistance converting your electricity into wasted thermal energy, stressing components far beyond their design limits. Ignoring it doesn’t make it safer; it just delays the moment when physics asserts itself more dramatically—through tripped breakers, melted plastic, or worse.

You don’t need to dismantle your holiday display to stay safe. You need awareness, accurate measurement, and intentional choices: choosing certified hardware, respecting circuit limits, optimizing airflow, and replacing aging equipment before it fails. These aren’t inconveniences—they’re the quiet disciplines of responsible electricity use. Every degree of avoided heat extends the life of your gear, protects your home, and preserves the joy of the season without compromise.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?