Sour cream is a beloved ingredient in kitchens around the world—creamy, tangy, and rich, it adds depth to everything from baked potatoes to stroganoff. But there’s nothing more disappointing than stirring it into a warm sauce only to see it break apart into grainy clumps and oily liquid. Why does this happen? And more importantly, how can you stop it?

The separation of sour cream in sauces isn’t a flaw in your cooking—it’s a predictable result of food chemistry. Understanding the science behind it gives you control over the outcome. This article breaks down the biology and physics of sour cream stability, explains why heat and acidity cause separation, and provides practical solutions so you can use sour cream confidently in any dish.

The Science Behind Sour Cream: What Is It Made Of?

Sour cream starts as regular cream, typically containing 18–20% milk fat. It becomes “sour” through bacterial fermentation. Specific strains of lactic acid bacteria—usually Lactococcus lactis or Leuconostoc mesenteroides—are added to pasteurized cream. These microbes consume lactose (milk sugar) and produce lactic acid as a byproduct.

This acidification lowers the pH of the cream from about 6.7 to around 4.5. As the pH drops, two key structural changes occur:

- Casein proteins (the main protein in milk) begin to denature and form a loose network that traps fat and water.

- Fat globules cluster together slightly, contributing to the thick texture.

The resulting gel-like structure is what gives sour cream its signature thickness and smooth mouthfeel. However, this delicate balance is vulnerable when exposed to additional stressors—especially heat and further acidity.

Why Sour Cream Separates in Hot Sauces

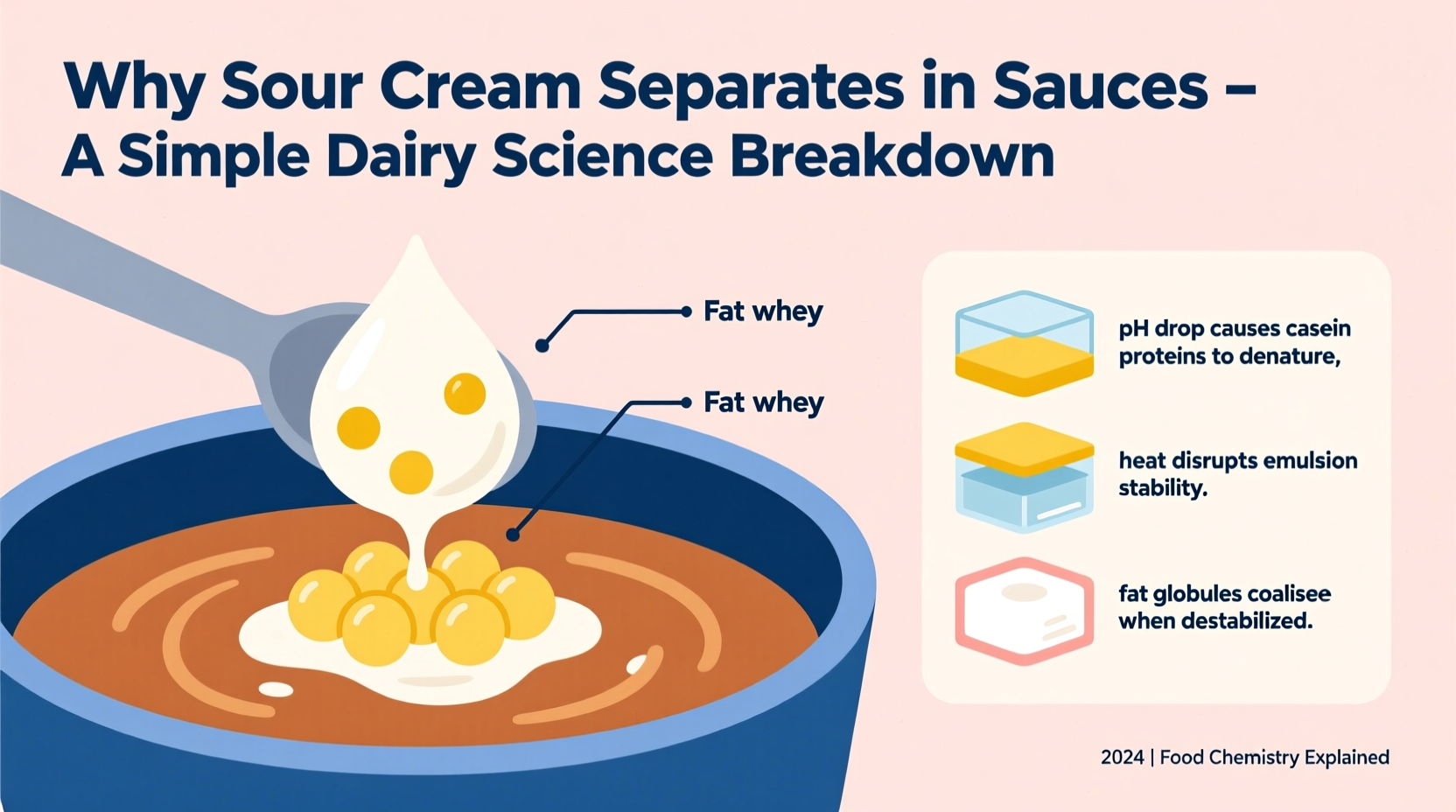

When sour cream separates in a sauce, you’re witnessing the breakdown of its emulsified structure. The primary culprits are temperature shock and pH imbalance.

Heat Disrupts Protein and Fat Bonds

Proteins in sour cream are folded into specific shapes that help stabilize the mixture of fat and water. When heated too quickly or too high, these proteins unravel (denature) and then clump together (coagulate). This process forces out the trapped water and oil, leading to visible separation.

Unlike heavy cream, which has a higher fat-to-protein ratio and stabilizers, sour cream has already undergone acidification. That means its proteins are already partially coagulated. Additional heat pushes them past their stability threshold.

Acidity Amplifies Instability

Adding sour cream to an already acidic sauce—such as one with tomatoes, wine, or vinegar—can accelerate separation. The lower pH increases the negative charge on casein proteins, causing them to repel each other and collapse the gel network.

In technical terms: at very low pH levels (below 4.6), casein micelles lose calcium and dissolve, breaking the protein matrix that holds the emulsion together.

“Dairy products like sour cream are stable within a narrow range of pH and temperature. Exceeding those limits—even briefly—can irreversibly disrupt their structure.” — Dr. Lena Peterson, Food Scientist, University of Wisconsin-Madison

How to Prevent Sour Cream from Curdling: A Step-by-Step Guide

Preventing separation isn’t about avoiding sour cream—it’s about managing conditions. Follow this sequence to incorporate sour cream smoothly into hot dishes.

- Temper the sour cream: Remove the pan from direct heat. Ladle out about ½ cup of the hot liquid and slowly whisk it into ¼ cup of sour cream in a separate bowl. This gradual warming prevents thermal shock.

- Repeat if needed: Add another splash of hot liquid and stir again until the sour cream is nearly the same temperature as the sauce.

- Stir back into the main pot: Gently fold the tempered sour cream into the larger batch. Keep the heat off or on the lowest setting.

- Do not boil: Once added, never bring the sauce to a simmer or boil. Gentle warming only.

- Add starch (optional): Mix sour cream with a small amount of cornstarch or flour before tempering. The starch absorbs excess moisture and reinforces the emulsion.

Smart Substitutions and Alternatives

If you're frequently struggling with sour cream separation, consider alternatives that behave better under heat.

| Ingredient | Best For | Heat Stability | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-fat sour cream | Cold dishes, finishing sauces | Poor (unless tempered) | Rich flavor but fragile when heated |

| Crème fraîche | Simmered sauces, soups | Excellent | Naturally higher fat (30%) and less acidic; resists curdling |

| Yogurt (Greek, full-fat) | Marinades, cold sauces | Fair (must be tempered) | More acidic than sour cream; prone to splitting |

| Soured cream with starch | Baking, casseroles | Good | Mix 1 tbsp cornstarch per ½ cup sour cream before adding |

| Cooking cream (ultra-pasteurized) | Long-simmered dishes | Very good | Stabilized with gums; designed for heat |

For example, crème fraîche is essentially soured cream made with a different bacterial culture and higher fat content. Its pH is slightly higher (around 5.0–5.5), and the fat helps protect proteins from heat damage. This makes it ideal for recipes like French onion soup or creamy mushroom sauces where prolonged heating is required.

Real Kitchen Scenario: Fixing a Broken Beef Stroganoff

Mark loves making beef stroganoff every winter. He sears the meat, sautés mushrooms, deglazes with brandy, and builds a rich broth. Then comes the sour cream—the final touch. But every time he adds it, the sauce turns lumpy and oily.

After reading up on dairy chemistry, Mark changes his method. Instead of dumping sour cream directly into the pot, he lets the sauce cool slightly off the burner. He mixes two tablespoons of cornstarch with a quarter cup of sour cream, then slowly whisks in a ladleful of warm sauce. After blending this mixture back in, he reheats gently on low. The result? Silky, luxurious stroganoff without a single curd.

His takeaway: “It wasn’t the recipe. It was how I was adding the sour cream. A few extra steps made all the difference.”

Common Myths About Sour Cream and Cooking

Misinformation often leads home cooks to avoid sour cream altogether. Let’s clear up some misconceptions.

- Myth: All dairy will curdle in tomato sauce.

Reality: While acidic environments increase risk, proper technique (like tempering) allows safe integration. Even ricotta and mascarpone can be stabilized in tomato-based dishes. - Myth: Adding lemon juice causes immediate separation.

Reality: Lemon juice lowers pH, but timing matters. Add it after cooling the dish slightly, or balance acidity with a pinch of baking soda. - Myth: Only “bad” sour cream separates.

Reality: Freshness affects taste and texture, but even premium sour cream will split under high heat. It’s physics, not spoilage.

Checklist: How to Use Sour Cream in Hot Dishes Without Separation

Use this checklist before adding sour cream to any warm dish:

- ✅ Remove pan from direct heat

- ✅ Let sauce cool slightly (below 180°F / 82°C)

- ✅ Bring sour cream to room temperature

- ✅ Mix sour cream with cornstarch (1 tsp per ¼ cup)

- ✅ Temper with warm liquid before adding

- ✅ Stir gently and avoid boiling afterward

- ✅ Serve immediately or chill if storing

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I re-blend separated sour cream sauce?

Once sour cream has fully separated, you cannot fully restore its original texture. However, you may improve appearance by blending in a tablespoon of cold butter or a splash of cream using an immersion blender. This won’t fix flavor loss, so prevention is always better.

Is it safe to eat curdled sour cream in a sauce?

Yes, curdled sour cream is generally safe to eat if the product was fresh and the dish hasn’t been overheated excessively. The separation is a physical change, not a sign of spoilage. However, texture and mouthfeel will be compromised.

Can I freeze dishes with sour cream?

No. Freezing damages the emulsion structure of sour cream. Upon thawing, it will release large amounts of whey and become grainy. Dishes relying on sour cream for creaminess should be consumed fresh or stored refrigerated for up to 3 days.

Conclusion: Mastering Dairy in Your Cooking

Understanding why sour cream separates in sauces transforms frustration into confidence. It’s not a failure of ingredients or effort—it’s a matter of respecting the boundaries of food science. By controlling temperature, managing acidity, and using smart techniques like tempering and starch stabilization, you can harness the rich flavor of sour cream without sacrificing texture.

Great cooking isn’t just about following recipes. It’s about knowing how ingredients behave and adjusting your approach accordingly. Whether you’re making tzatziki, enchiladas, or a comforting bowl of potato soup, these principles empower you to cook with precision and creativity.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?