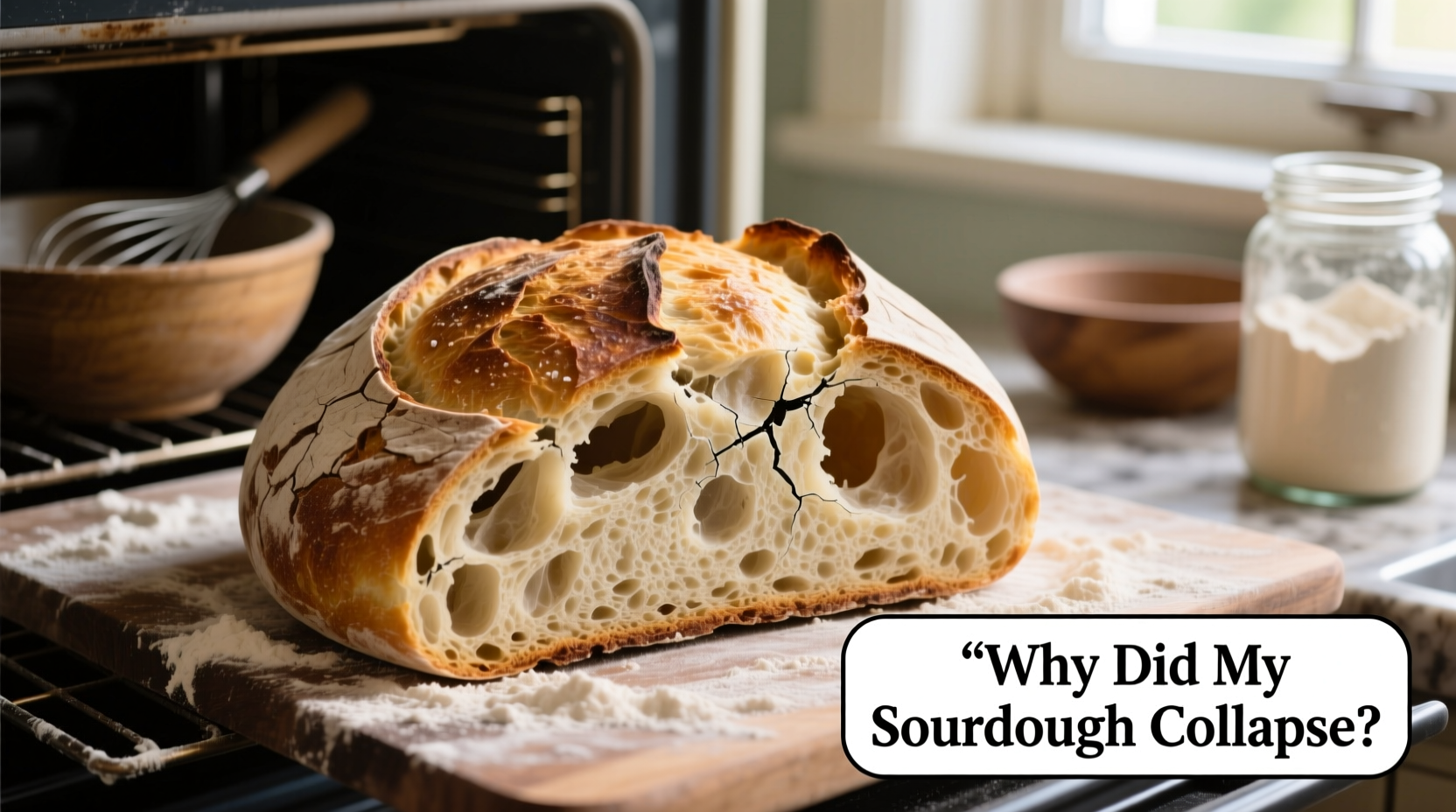

Sourdough baking is both an art and a science, and even experienced bakers encounter setbacks. One of the most disheartening moments? Watching your beautifully proofed loaf rise confidently into the oven—only to deflate minutes later. A collapsed sourdough loaf isn’t just disappointing; it’s a signal that something went wrong in the fermentation, shaping, or baking process. Understanding the root causes behind this issue is essential for improving your technique and achieving consistent, open-crumbed loaves with a crisp crust and stable structure.

A sourdough collapse typically occurs when the gluten network can’t support the expansion of gases during oven spring. This structural failure may stem from underdevelopment, overproofing, weak starter activity, or improper handling. The good news: each of these factors is diagnosable and correctable. By systematically evaluating your process, you can identify what went wrong and refine your approach for better results.

Understanding Oven Spring and Why Collapse Happens

Oven spring refers to the rapid rise that occurs in the first 10–15 minutes of baking, driven by trapped carbon dioxide expanding and steam creation within the dough. For this to happen successfully, three elements must align: a strong gluten structure, active yeast and bacteria producing gas, and proper heat transfer from the oven.

When a loaf collapses, it means the internal structure failed to contain the pressure of expanding gases. This can occur at different stages:

- Mid-bake collapse: Often due to overproofing or weak gluten development.

- Immediate deflation upon scoring: Suggests the dough was already at maximum tension before baking.

- Post-oven collapse: May indicate underbaking or moisture retention weakening the crumb.

The key is not just preventing collapse but understanding what each symptom reveals about your bake.

Common Causes of Sourdough Collapse (and How to Fix Them)

1. Overproofing: The Most Frequent Culprit

Overproofing happens when the dough ferments too long, exhausting its sugar reserves and weakening the gluten matrix. While underproofed dough lacks volume, overproofed dough collapses because it has no structural integrity left to withstand oven spring.

Signs of overproofing include:

- Dough that sags when touched or removed from the banneton

- Excessive bubbling on the surface

- Lack of elasticity when handled

To prevent overproofing, adjust your bulk fermentation and final proof times based on temperature. Cooler environments slow fermentation, while warm kitchens accelerate it. Use a clear plastic tub or jar to monitor rise volume—ideal bulk fermentation ends when the dough has increased by 50–75%, not necessarily after a fixed time.

2. Weak or Inactive Starter

Your sourdough starter is the engine of your bread. If it's sluggish or underripe, it won’t produce enough gas to create lift—and worse, it may continue fermenting during baking, causing late gas production that destabilizes the structure.

A healthy starter should double within 4–6 hours of feeding at room temperature (around 72°F/22°C), with visible bubbles throughout and a pleasant tangy aroma. Using a starter at its peak—or slightly before—is crucial.

“Never bake with a starter that hasn’t peaked. Baking with a falling starter leads to poor oven spring and unpredictable fermentation.” — Ken Forkish, artisan baker and author of *Flour Water Salt Yeast*

3. Poor Gluten Development

Gluten forms the elastic scaffold that traps gas and supports the loaf. Without sufficient development, the dough tears easily and can't hold shape.

Autolyse (resting flour and water before adding salt and starter) improves gluten formation. During bulk fermentation, perform stretch-and-folds every 30 minutes for the first two hours to strengthen the network. Underdeveloped dough feels slack and sticky; well-developed dough is smooth, supple, and holds tension.

4. Improper Scoring Technique

Scoring controls where the loaf expands. Deep, confident cuts allow steam and gas to escape in a predictable way. Shallow or hesitant slashes cause the dough to burst unpredictably, sometimes leading to partial collapse.

Use a sharp lame or razor blade at a 30–45° angle, cutting about ½ inch deep. Avoid dragging the blade, which seals the cut. Practice consistent patterns like a single slash, tic-tac-toe, or spiral designs to manage expansion evenly.

5. Inadequate Oven Temperature or Steam

Low oven temperature delays crust formation, allowing the interior to expand too quickly and rupture. Similarly, insufficient steam prevents proper gelatinization of starches, which weakens the crust’s ability to expand.

Preheat your oven and baking vessel (Dutch oven, combo cooker, or baking stone) for at least 45 minutes at 450–475°F (230–245°C). Introduce steam via a water pan, ice cubes, or spritzing the oven walls (if safe). Maintain steam for the first 20 minutes of baking.

Troubleshooting Checklist: Prevent Collapse Before It Happens

Use this checklist before every bake to catch potential issues early:

- ✅ Is my starter active and peaking? (Doubled, bubbly, passes float test?)

- ✅ Did I autolyse for 30–60 minutes to enhance gluten formation?

- ✅ Did I perform adequate stretch-and-folds during bulk fermentation?

- ✅ Has the dough risen 50–75% during bulk, not doubled?

- ✅ Is the final proof timed correctly? (Typically 1–4 hours at room temp or overnight in fridge)

- ✅ Does the dough pass the poke test without collapsing?

- ✅ Is my oven fully preheated with vessel inside?

- ✅ Am I scoring deeply and confidently with a sharp blade?

- ✅ Am I using steam during the first phase of baking?

- ✅ Is the internal temperature at least 205–210°F (96–99°C) when done?

Step-by-Step Guide to a Structurally Sound Sourdough Loaf

Follow this timeline to minimize collapse risk and maximize success:

- Feed starter 8–12 hours before mixing: Ensure it peaks just before use.

- Mix and autolyse (0:00): Combine flour and water; rest 30–60 minutes.

- Add starter and salt (1:00): Mix to form cohesive dough.

- Bulk fermentation (1:15–3:15): Perform 3–4 sets of stretch-and-folds over 2 hours. Let rest until 50–75% increased in volume.

- Shape and bench rest (3:15–3:45): Pre-shape, rest 20–30 minutes, then final shape.

- Final proof (4:15–8:15 or longer): Room temp for 1–4 hours, or refrigerate for 8–16 hours.

- Preheat oven (7:45 if baking same day): Heat oven and Dutch oven to 475°F (245°C) for 45+ minutes.

- Score and bake (final proof complete): Score deeply, transfer to hot pot, cover, bake 20 minutes.

- Uncover and finish baking: Reduce heat to 450°F (230°C), bake 20–25 more minutes until deep golden and internal temp ≥208°F.

- Cool completely: Wait at least 2 hours before slicing to preserve crumb structure.

This structured approach ensures each phase builds strength and stability, reducing the likelihood of mid-bake failure.

Do’s and Don’ts: Key Practices for Stable Sourdough Structure

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Use a ripe, active starter at peak inflation | Use a starter that’s past its peak or inactive |

| Perform stretch-and-folds to build strength | Rely solely on mixing for gluten development |

| Proof in the refrigerator for better control | Leave dough to final proof unattended for 6+ hours at room temp |

| Score with a sharp blade at a shallow angle | Use a dull knife or cut too vertically |

| Preheat baking vessel thoroughly | Place dough in a cold or inadequately heated oven |

| Allow full cooling before slicing | Cut into hot bread, causing gummy texture and collapse |

Real Example: Recovering From Repeated Collapse

Jessica, a home baker in Portland, struggled with collapsing loaves for months. Her dough looked perfect in the banneton but flattened dramatically in the oven. She followed recipes closely but overlooked environmental variables.

After tracking her process, she realized two critical mistakes: her kitchen was warmer than average (78°F), accelerating fermentation, and she was using her starter 2 hours after feeding—when it had already peaked and fallen. She adjusted by feeding her starter earlier in the morning, refrigerating it post-peak, and shortening her final proof from 4 hours to 2.5. She also began using a cooler water ratio to slow fermentation.

The result? Within two bakes, her loaves held their shape through oven spring and developed a balanced, airy crumb. Jessica now logs ambient temperature and starter behavior daily, treating sourdough as a responsive system rather than a rigid recipe.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I rescue a collapsing loaf mid-bake?

No intervention can stop a collapse once it starts. However, if you notice early signs (excessive puffing or cracking), slightly increasing the oven temperature may help set the crust faster. Prevention is far more effective than mid-bake fixes.

Why does my sourdough rise beautifully but fall when I score it?

This usually indicates overproofing. The dough has reached maximum gas retention and any release of tension—like a score—causes it to deflate. Try reducing final proof time or switching to a retarded (cold) proof for better control.

Does high hydration always lead to collapse?

Not necessarily. High-hydration doughs (80%+) are more challenging to handle but can be stable with strong gluten development and proper shaping. Beginners should start with 70–75% hydration to build skills before advancing.

Conclusion: Build Confidence Through Consistency

A collapsed sourdough loaf isn’t a failure—it’s feedback. Each bake teaches you more about your flour, environment, starter, and technique. The path to reliable, oven-spring-rich bread lies in observation, adjustment, and patience. Focus on building strong gluten, timing your proofs accurately, and mastering oven conditions. Over time, you’ll develop an intuitive sense for when your dough is ready and how it will behave under heat.

Sourdough rewards attention to detail. With the right approach, even a history of collapsed loaves can transform into a repertoire of tall, resilient, crackling boules. Trust the process, keep notes, and don’t let one deflated loaf discourage you. Your breakthrough bake is closer than you think.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?