A sourdough starter is a living culture of wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria, thriving on flour and water. When balanced, it emits a pleasantly tangy, slightly fruity aroma—like yogurt or ripe apples. But when something goes wrong, the smell can turn foul: rotten eggs, acetone, vomit, or even gym socks. These odors are warning signs that your starter’s microbial ecosystem is out of balance. While unsettling, most issues are fixable with proper care and understanding.

The key to reviving a smelly starter lies in identifying the root cause. Was it underfed? Left too long without maintenance? Exposed to extreme temperatures? Each misstep disrupts the delicate harmony between yeast and bacteria. This guide breaks down the most common reasons behind bad smells, how to interpret what your starter is trying to tell you, and actionable steps to restore its health—so you can bake confidently again.

Understanding Normal vs. Abnormal Starter Smells

Not all sourdough smells are created equal. A healthy starter evolves through stages of fermentation, each with distinct aromas:

- Freshly fed (0–4 hours): Sweet, wheaty, like fresh dough.

- Peaking (6–12 hours): Tangy, yogurt-like, with a hint of fruitiness.

- Post-peak (12+ hours): Sharper acidity, vinegar notes—still normal if used promptly.

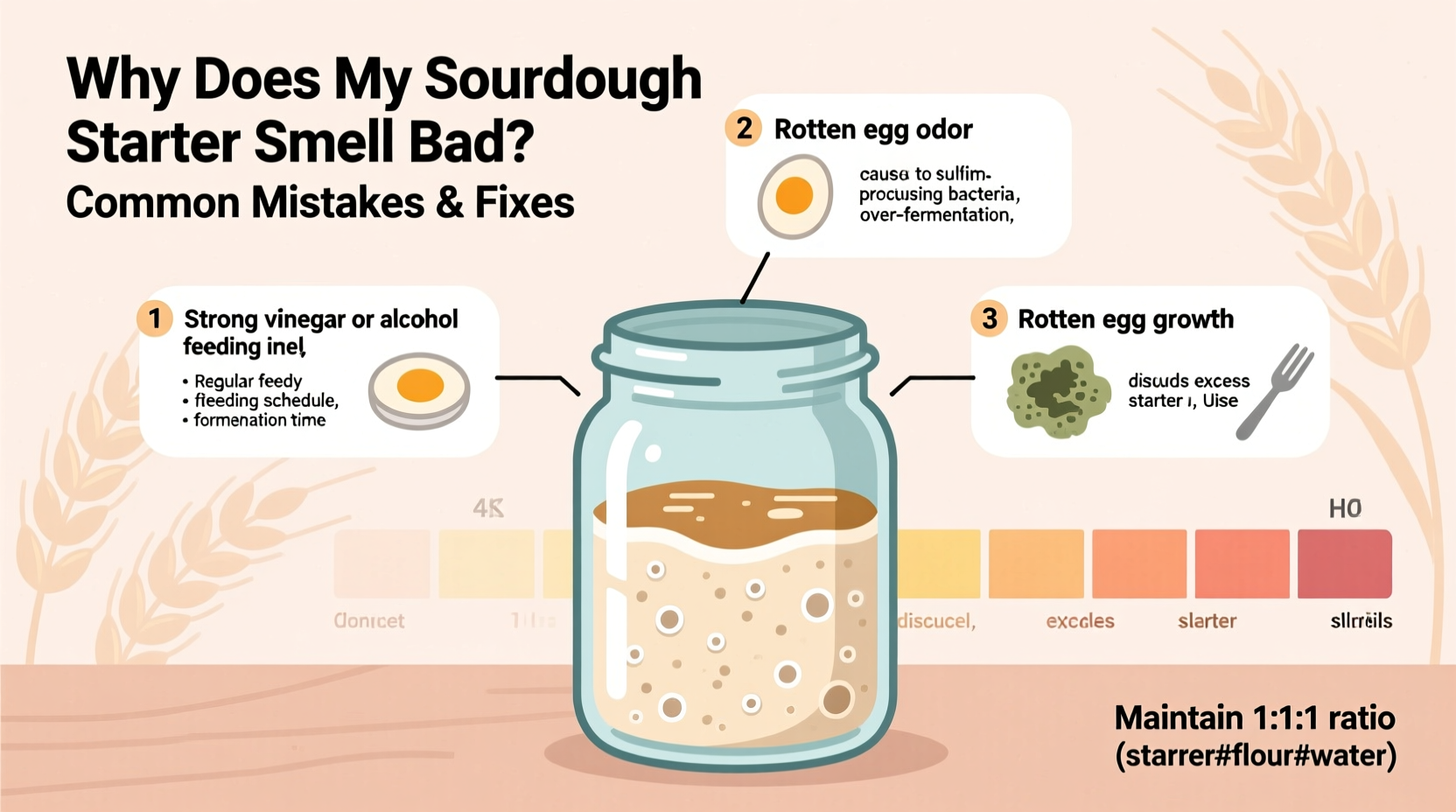

Abnormal odors, however, signal imbalance. Here’s what different smells typically mean:

| Smell | Possible Cause | Severity |

|---|---|---|

| Rotten eggs / sulfur | Hungry starter producing hydrogen sulfide | Moderate – fixable with feeding |

| Acetone / nail polish remover | Starved starter breaking down proteins | High – requires immediate attention |

| Vomit / cheesy | Overgrowth of heterofermentative bacteria | High – may need multiple refreshments |

| Moldy / musty | Contamination or poor hygiene | Critical – discard if mold is visible |

| No smell at all | Dormant or dead culture | Variable – depends on temperature and feed history |

While some off-odors resolve after a few consistent feedings, persistent foul smells suggest deeper issues in maintenance habits.

Common Mistakes That Cause Bad Smells

Most sourdough problems stem from predictable errors—even experienced bakers make them. Recognizing these pitfalls is the first step toward correction.

1. Infrequent or Inconsistent Feeding

When a starter isn’t fed regularly, beneficial microbes run out of food. Yeast and lactobacilli begin consuming their own waste products, leading to the production of alcohols and sulfur compounds. Acetone and rotten egg smells are classic signs of starvation.

2. Using Chlorinated Tap Water

Chlorine and chloramines in municipal water suppress microbial activity. While not always lethal, they weaken the culture over time, allowing undesirable bacteria to dominate.

3. Poor Temperature Control

Sourdough thrives between 70°F and 78°F (21°C–26°C). Cooler temps slow fermentation, increasing risk of hooch and off-flavors. Warmer temps accelerate fermentation but favor acetic acid bacteria, which produce sharper, more pungent acids.

4. Contamination from Unsanitary Tools

Using dirty jars, spoons, or hands introduces competing microbes. Mold spores, wild yeasts, or bacteria from kitchen surfaces can overpower your starter.

5. Overreliance on Whole Grain Flours Without Adjustment

Whole rye or whole wheat flours ferment faster due to higher nutrient content. If not adjusted for, this leads to rapid acid buildup and unpleasant aromas.

“Many people think a sourdough starter is ‘set and forget,’ but it’s more like a pet—it needs routine, clean conditions, and the right diet.” — Dr. Karl De Smedt, microbiologist and sourdough preservation specialist at the Sourdough Library in Belgium

Step-by-Step Fix: Reviving a Smelly Starter

If your starter reeks but shows no mold, don’t give up. Most cultures can be revived within 3–5 days with disciplined care. Follow this timeline:

- Day 1: Discard and Refresh (1:2:2 ratio)

Discard all but 25g of starter. Feed with 25g water and 25g unbleached all-purpose flour. Use filtered or bottled water if tap is chlorinated. Stir well, cover loosely, and keep at room temperature (70–75°F). - Day 2: Double Feedings

Repeat the 1:2:2 feeding every 12 hours (morning and evening). This rebuilds population density and flushes out accumulated acids. - Day 3: Evaluate Rise and Smell

After the second feeding, check for bubbles, expansion (should double in 6–12 hours), and aroma. It should smell tangy but clean. If still foul, continue twice-daily feedings. - Day 4–5: Normalize Routine

Once the starter consistently rises and smells pleasant, return to a once-daily feeding if keeping at room temp, or store in the fridge with weekly refreshments.

This process dilutes harmful byproducts, reintroduces oxygen, and provides fresh nutrients to encourage healthy microbial growth.

When to Start Over

Discard the starter entirely if you see any of the following:

- Visible mold (fuzzy spots in pink, green, black, or orange)

- Pink or orange liquid (not brown hooch)

- No activity after 5 days of regular feeding

In such cases, contamination has likely taken over, and recovery is unlikely.

Tips for Long-Term Starter Health

Prevention is simpler than revival. Adopting consistent habits ensures your starter remains vibrant and odor-appropriate.

Use the Right Flour

Unbleached all-purpose or bread flour offers a stable baseline. For added resilience, mix in 10–20% rye flour, which contains nutrients that boost microbial diversity.

Control Fermentation Speed

If your kitchen runs hot, refrigerate the starter between uses. Cold slows acid production and prevents over-fermentation. If it’s cold, place the jar near a warm appliance or use a proofing box.

Stir Frequently

Stirring your starter 2–3 times daily (even if not feeding) aerates the culture, discouraging anaerobic bacteria that produce foul odors.

Keep a Backup

Once your starter is healthy, dry a portion: spread a thin layer on parchment, let dry for 24–48 hours, then crumble and store in an airtight container. Rehydrate with water and flour if your main culture fails.

Real Example: Recovering a Week-Old Neglected Starter

Sarah, a home baker in Portland, returned from vacation to find her starter topped with dark hooch and emitting a strong acetone smell. She almost discarded it—but decided to try reviving it.

She poured off the hooch, stirred the remaining paste, and fed it 1:2:2 with filtered water and all-purpose flour. The next morning, it showed minimal rise and still smelled sharp. She repeated the feeding, this time twice daily.

By day three, bubbles appeared throughout, and the smell shifted from nail polish to apple cider. On day five, it doubled in size within eight hours and passed the float test. Sarah saved her starter and resumed baking—proof that patience and consistency pay off.

Do’s and Don’ts of Sourdough Starter Care

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Feed regularly based on temperature and activity | Leave starter unfed for over a week at room temp |

| Use non-chlorinated water | Use distilled water long-term (lacks minerals microbes need) |

| Store in a clean, breathable container (loose lid or cloth cover) | Seal tightly—pressure buildup can crack jars |

| Discard and feed before peak collapse | Wait until hooch forms regularly—it stresses the culture |

| Keep a backup culture or dried sample | Assume one mistake kills the starter permanently |

Frequently Asked Questions

Is hooch dangerous?

No. Hooch—the dark liquid that forms on top—is alcohol produced during fermentation. It’s a sign your starter is hungry, not dead. Pour it off or stir it in before feeding. However, pink or orange liquid indicates spoilage and requires discarding.

Can I use my smelly starter in bread?

If the smell is only mildly sour or alcoholic, yes—especially in recipes calling for longer fermentation. But if it smells like rot, chemicals, or vomit, the bread may have off-flavors or fail to rise. Wait until the starter smells clean and active.

Why does my starter smell worse in the fridge?

Cold slows yeast activity but not acid production entirely. Lactic acid continues to build slowly, making the starter more sour over time. This is normal. Simply discard, feed, and leave at room temperature for 1–2 cycles to reactivate.

Conclusion: Trust the Process, Not Just the Smell

A bad smell doesn’t mean failure—it means feedback. Your sourdough starter is communicating its needs. Whether it’s hunger, poor water quality, or temperature stress, each issue has a solution rooted in consistency and observation.

Reviving a troubled starter teaches patience and deepens your understanding of fermentation. With the right adjustments, most starters bounce back stronger than before. Don’t rush to throw it out. Instead, apply the fixes outlined here, track your progress, and give it a few days.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?