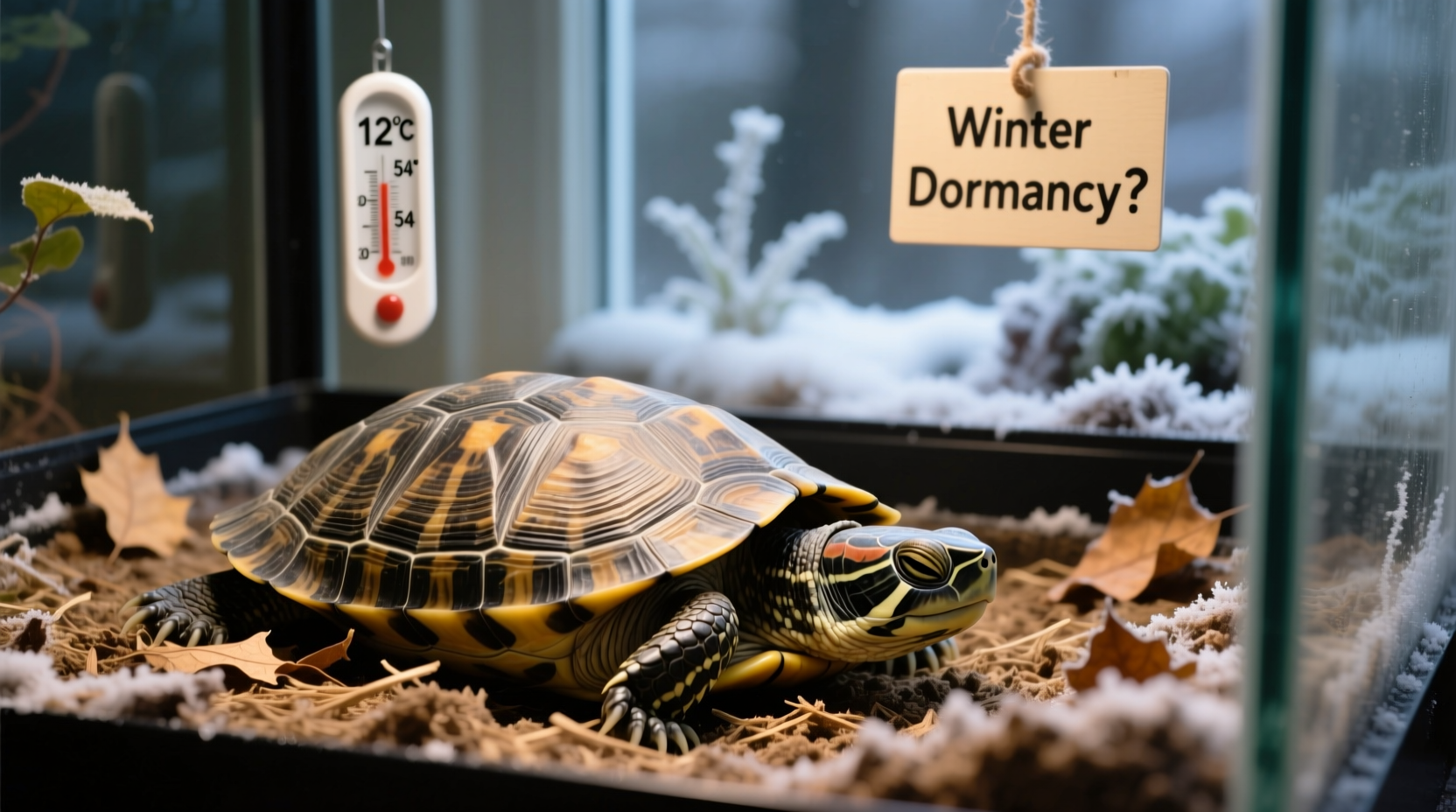

As the temperature drops and daylight shortens, many turtle owners notice a sudden change in their pet’s behavior: they stop eating. This shift can be alarming, especially if you're unsure whether it's a natural seasonal response or a sign of illness. The truth is, both hibernation and sickness can cause appetite loss in turtles during winter. Understanding the difference is crucial for your turtle’s health and survival.

Turtles are ectothermic, meaning their body temperature—and by extension, their metabolism—depends on the environment. When temperatures fall below certain thresholds, their internal systems slow down significantly. In the wild, this triggers brumation (the reptilian equivalent of hibernation), a state of dormancy that helps them survive cold months with minimal food and activity. But not all turtles brumate safely in captivity, and some symptoms of illness mimic those of brumation. Recognizing which process is at play can mean the difference between life and death.

Understanding Brumation: Is Your Turtle Sleeping, Not Sick?

Brumation is a natural physiological adaptation in many temperate-zone turtle species, including box turtles, painted turtles, and snapping turtles. As autumn progresses, decreasing light and cooler temperatures signal the onset of brumation. During this period, a turtle’s heart rate, respiration, and digestion slow dramatically. Appetite diminishes as the digestive tract shuts down, making feeding not only unnecessary but potentially dangerous.

In the wild, turtles prepare for brumation by gradually reducing food intake weeks in advance. They empty their digestive system to avoid rotting food buildup, which could lead to fatal infections while dormant. In captivity, this same process may occur if ambient temperatures drop below 50°F (10°C). A turtle entering brumation will often become lethargic, spend more time buried in substrate or submerged at the bottom of a pond, and show little interest in food—even their favorite treats.

“Brumation is not sleep—it’s a controlled metabolic slowdown. Healthy turtles can survive months without food during this phase, but only if they enter it in good condition.” — Dr. Laura Bennett, Reptile Veterinarian, Wildlife Care Center

However, not all turtles should brumate. Young turtles (under 3 years), sick individuals, or tropical species like red-eared sliders kept indoors typically do not require or benefit from brumation. Forcing or allowing an unprepared turtle to brumate can result in dehydration, infection, or starvation.

Signs of Illness vs. Normal Brumation Behavior

Distinguishing between a healthy brumating turtle and a sick one requires careful observation. While both may exhibit reduced activity and appetite, key differences lie in physical condition, responsiveness, and environmental context.

| Behavior/Condition | Normal Brumation | Potential Illness |

|---|---|---|

| Appetite | Gradually decreases; stops completely before full dormancy | Sudden loss, often accompanied by refusal of all food types |

| Energy Level | Lethargic but responsive to touch or disturbance | Unresponsive, weak, or unable to lift head |

| Eyes | Open occasionally, clear and bright | Swollen, sunken, or constantly closed with discharge |

| Nose | Clear, no discharge | Bubbles from nostrils, mucus, frequent sneezing |

| Weight | Stable or slight gradual loss | Rapid weight loss, muscle wasting |

| Environment | Cool temps (40–50°F), seasonal timing | Occurs in warm enclosures or off-season |

A turtle that stops eating in November while its tank temperature dips to 48°F is likely preparing for brumation. One that refuses food in July in a properly heated enclosure is almost certainly unwell. Respiratory infections, parasitic infestations, mouth rot, and gastrointestinal blockages are common causes of appetite loss in captive turtles.

When Should You Prevent Brumation?

If you’re keeping a turtle as a pet in a climate-controlled home, brumation is often unnecessary and sometimes risky. Many indoor setups maintain stable temperatures year-round, which discourages natural brumation cycles. If you wish to prevent brumation, ensure the following:

- Maintain basking temperatures between 85–90°F (29–32°C)

- Keep water temperature above 70°F (21°C) for aquatic species

- Provide 10–12 hours of UVB lighting daily

- Continue offering food regularly

By stabilizing heat and light, you signal to your turtle that it’s still “active season.” Most healthy adult turtles will continue normal feeding patterns under these conditions. However, some stubborn individuals—especially those with strong seasonal instincts—may still attempt to brumate. In such cases, monitor closely and intervene if signs of distress appear.

Step-by-Step: How to Safely Support a Brumating Turtle

If you decide to allow brumation—or if your outdoor pond turtle naturally enters dormancy—follow this timeline to ensure safety:

- Weeks 6–4 Before Cooling: Gradually reduce feeding frequency. Offer easily digestible foods like leafy greens and insects. Stop all food by week 4 to ensure the gut is fully cleared.

- Weeks 3–2: Lower water or ambient temperature slowly by 2–3°F per day until reaching 50°F (10°C). Maintain UVB lighting during daytime hours.

- Week 1: Move turtle to brumation setup—this could be a cool basement, insulated outdoor pond, or refrigerated unit (for small species). Ensure humidity remains high (70–80%) to prevent dehydration.

- During Brumation: Check monthly. The turtle should feel firm, respond slightly to touch, and show no mold, swelling, or foul odor. Weigh every 4–6 weeks; acceptable loss is up to 1% of body weight per month.

- Emergence (Spring): Reverse the process. Warm gradually over 7–10 days. Offer shallow water first, then small meals after 3–5 days. Resume full diet within two weeks.

“Rushing emergence is just as dangerous as forcing brumation. Always re-warm slowly—your turtle’s organs need time to reboot.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Herpetological Medicine Specialist

Common Illnesses That Cause Loss of Appetite

If your turtle isn’t in a cool environment and still won’t eat, illness is likely. The most common culprits include:

- Respiratory Infections: Caused by low temperatures, poor ventilation, or dirty water. Symptoms include labored breathing, nasal discharge, buoyancy issues, and gaping mouth.

- Parasites: Internal worms or protozoa disrupt digestion and nutrient absorption. Often detected through fecal exams. May cause diarrhea, weight loss, and lethargy.

- Hypovitaminosis A (Vitamin A Deficiency): Leads to swollen eyes, ear abscesses, and poor skin shedding. Common in turtles fed iceberg lettuce or poor diets.

- Mouth Rot (Ulcerative Stomatitis): Bacterial infection causing yellow plaques, bleeding gums, and refusal to open mouth.

- Shell Rot: Fungal or bacterial infection of the shell, often due to poor water quality. Can cause systemic illness and appetite suppression.

Any of these conditions require prompt veterinary attention. Do not assume your turtle is “just brumating” if it shows abnormal physical signs. Delayed treatment can lead to sepsis, organ failure, or death.

Checklist: Is My Turtle Brumating or Sick?

Use this checklist to assess your turtle’s condition objectively:

- ✅ Has the ambient temperature dropped below 55°F (13°C)?

- ✅ Did appetite decrease gradually over weeks?

- ✅ Is the turtle active enough to move to a sheltered spot?

- ✅ Are eyes clear and open occasionally?

- ✅ Is there no nasal discharge, swelling, or foul odor?

- ✅ Has weight remained stable or decreased very slowly?

- ❌ Are there bubbles from the nose or open-mouth breathing?

- ❌ Is the turtle listless, floating oddly, or unresponsive?

- ❌ Did appetite stop suddenly despite warm conditions?

If most answers are “yes” to the first six and “no” to the last three, brumation is likely. If the reverse is true, treat it as a medical emergency.

Mini Case Study: Bella the Box Turtle

Bella, a 5-year-old Eastern box turtle, lived in an outdoor enclosure in Pennsylvania. In late October, her owner noticed she stopped eating strawberries—her usual favorite. Over the next two weeks, Bella burrowed into leaf litter and became less active. The nighttime temperature averaged 45°F.

Concerned, the owner consulted a reptile vet. After a physical exam and weight check (Bella had lost only 2% of her body weight over four weeks), the vet confirmed Bella was entering natural brumation. The owner was advised to leave her undisturbed, protect the enclosure from predators, and monitor monthly.

In March, as temperatures rose, Bella emerged on her own. She was offered water and soaked gently. After five days, she accepted a small earthworm. By week two, she resumed normal feeding. No intervention was needed—just observation and patience.

In contrast, Max, a young red-eared slider kept indoors, stopped eating in December despite a basking lamp and water heater. He developed swollen eyes and floated sideways. A vet diagnosed a severe respiratory infection and vitamin A deficiency. With antibiotics and nutritional support, Max recovered—but only after timely care.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I force my turtle to eat during winter?

No. Forcing food on a brumating turtle can lead to indigestion and fatal infections. If your turtle is healthy and cooling down, let it follow its natural cycle. If it’s warm and not eating, investigate illness.

Do all turtles brumate?

No. Tropical species like African sideneck turtles or mata mata turtles do not brumate. Even among temperate species, juveniles and sick turtles should not be allowed to brumate without veterinary approval.

How long can a turtle go without eating?

A healthy adult turtle can survive 2–3 months without food during brumation. Outside of dormancy, more than two weeks without eating warrants investigation. Hatchlings should never go more than a few days without food.

Final Thoughts: Know Your Turtle, Trust Observation

Your turtle’s loss of appetite in winter isn’t automatically a crisis—but it shouldn’t be ignored either. Nature has equipped many turtles to slow down when seasons change, but captivity alters those rules. The decision to allow brumation or prevent it depends on species, age, health, and environment.

The most important tool you have is observation. Monitor behavior, track weight, and understand what’s normal for your individual turtle. When in doubt, consult a qualified reptile veterinarian. Never guess when health is at stake.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?