It starts with a faint tickle, then a sharp pinch, followed by an insistent, maddening itch. A mosquito has bitten you. Within seconds, your fingers are instinctively moving toward the spot. The moment your nails dig in, a wave of relief washes over you. It feels incredibly satisfying—almost euphoric. But why? And why does the itch return, often stronger than before? The answer lies deep within your nervous system, immune response, and even your brain’s reward circuitry. This article unpacks the surprising neuroscience and biology behind one of humanity’s most universal habits: scratching mosquito bites.

The Biology of a Mosquito Bite

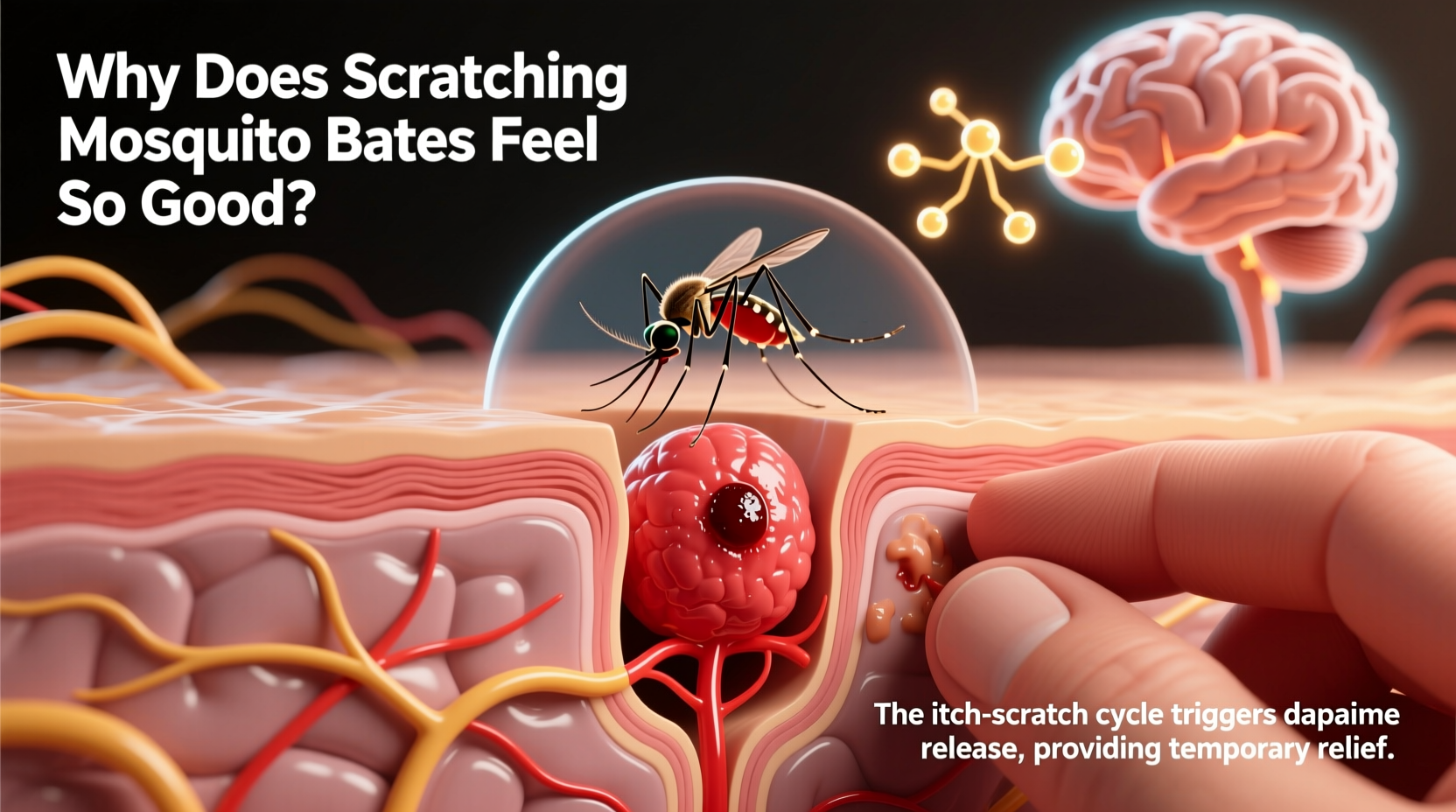

When a female mosquito pierces your skin, she isn’t just taking blood—she’s injecting a cocktail of proteins designed to prevent clotting and suppress your immune response. These foreign substances trigger your body’s defense mechanisms. Mast cells in the skin release histamine, a chemical that increases blood flow and attracts white blood cells to the area. Histamine also stimulates nearby nerve endings responsible for sensing itch, known as C-fibers.

These specialized nerves send signals through your spinal cord and up to your brain, specifically activating regions like the somatosensory cortex (which maps bodily sensations) and the anterior cingulate cortex (involved in emotional processing). The result? An intense, localized itch that demands attention.

Why Scratching Feels So Good: The Neurological Reward

Scratching provides immediate sensory feedback that temporarily overrides the itch signal. When you scratch, you activate pain receptors (nociceptors) and mechanoreceptors in the skin. These signals travel along faster neural pathways than itch signals, effectively \"jamming\" the original message. This phenomenon is known as counter-irritation.

But the pleasure goes beyond simple distraction. Functional MRI studies have shown that scratching activates the nucleus accumbens and the ventral tegmental area—key components of the brain’s dopamine-driven reward system. These are the same regions lit up by eating delicious food or receiving praise. In essence, scratching an itch gives your brain a small but measurable dopamine hit.

“Scratching is not just a reflex—it's a behavior reinforced by the brain’s reward circuitry. That’s why it’s so hard to stop, even when we know it causes harm.” — Dr. Gil Yosipovitch, Chair of Dermatology at the Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami

This neurological reward explains why people with chronic itch conditions often scratch until they bleed. The temporary relief outweighs the long-term damage—at least in the moment.

The Dangerous Cycle: Itch, Scratch, Repeat

While scratching feels good initially, it sets off a destructive loop. Mechanical trauma from scratching damages skin cells, prompting the release of more inflammatory chemicals like serotonin and prostaglandins. These substances further sensitize nerve endings, amplifying the sensation of itch. This creates what dermatologists call the itch-scratch cycle: the more you scratch, the itchier it gets.

In some cases, excessive scratching leads to lichenification—a thickening of the skin due to constant irritation. Open wounds can become infected with bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus, turning a minor annoyance into a medical issue.

Do’s and Don’ts of Managing Mosquito Bites

| Action | Recommended? | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Scratch lightly with fingernails | No | Increases inflammation and risk of infection |

| Apply hydrocortisone cream | Yes | Reduces inflammation and blocks histamine effects |

| Use a cold spoon or ice pack | Yes | Numbing effect reduces nerve signaling |

| Pop or puncture the bite | No | Introduces bacteria and delays healing |

| Take an antihistamine (e.g., diphenhydramine) | Yes | Blocks histamine systemically, reducing overall itch |

Breaking the Cycle: Science-Backed Alternatives to Scratching

If scratching is counterproductive, what can you do instead? The key is to interrupt the itch signal without damaging the skin. Here are several evidence-based strategies:

- Cool the Skin: Cold constricts blood vessels and slows nerve conduction, dulling both itch and inflammation. Use a wrapped ice pack for 5–10 minutes.

- Topical Anti-Itch Agents: Calamine lotion, menthol creams, or low-dose hydrocortisone reduce local irritation and calm overactive nerves.

- Distract the Brain: Engage in activities that occupy your attention—reading, stretching, or even tapping near (but not on) the bite. Studies show that tactile distraction can reduce perceived itch intensity.

- Wear Loose Clothing: Fabric rubbing against a bite can worsen irritation. Choose breathable cotton and avoid tight sleeves or waistbands.

- Moisturize: Dry skin exacerbates itchiness. A fragrance-free moisturizer helps restore the skin barrier and reduces sensitivity.

Real-World Example: The Campground Itch Spiral

Consider Sarah, an avid hiker who spent a weekend camping near a lake. Unprotected, she received over a dozen mosquito bites on her arms and legs. By the second night, the itching was unbearable. She scratched several bites until they bled. The next morning, two bites were swollen, warm to the touch, and oozing—a sign of bacterial infection. She had to cut her trip short and visit urgent care, where she was prescribed antibiotics.

Sarah’s experience illustrates how a natural, seemingly harmless reaction can escalate quickly. With better tools—like insect repellent, antihistamines, and cooling gels—she could have avoided discomfort and medical complications.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does scratching actually make the itch worse?

Yes. Scratching triggers the release of more histamine and inflammatory cytokines, which heighten nerve sensitivity. This creates a feedback loop where the itch returns stronger after each scratch.

Why do some people react more strongly to mosquito bites than others?

Immune responses vary widely. Some individuals develop tolerance after repeated exposure (“hardening”), while others—especially children or those with sensitive immune systems—experience larger, longer-lasting welts. Genetics and previous exposure history play key roles.

Are there any long-term risks to scratching mosquito bites?

Beyond infection, chronic scratching can lead to scarring, hyperpigmentation, or permanent changes in skin texture. In rare cases, persistent scratching may contribute to neurodermatitis, a condition where localized patches become perpetually itchy.

Conclusion: Understanding to Heal

The urge to scratch a mosquito bite is deeply rooted in human biology—a mix of immune defense, nerve signaling, and brain chemistry. While scratching offers fleeting satisfaction, it ultimately prolongs discomfort and risks harm. By understanding the science behind the itch, you gain power over the impulse. Replace scratching with smarter, gentler interventions: cool the skin, block histamine, and protect the area from further irritation.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?