Every spring and fall, clocks across most of the United States jump forward or fall back by one hour. This ritual—known as Daylight Saving Time (DST)—has been a part of American life for over a century. While many people adjust automatically, few understand why we do it, who started it, or whether it still makes sense today. This article explains the origins, rationale, and ongoing debate around DST, offering clarity on one of the nation’s most persistent time quirks.

The Origins of Daylight Saving Time

Daylight Saving Time did not begin in the United States. The idea is often credited to Benjamin Franklin, who in 1784 humorously suggested Parisians could save candle wax by waking earlier to use morning sunlight. However, the modern concept of DST was first seriously proposed by New Zealand entomologist George Hudson in 1895 and later championed by British builder William Willett in 1907.

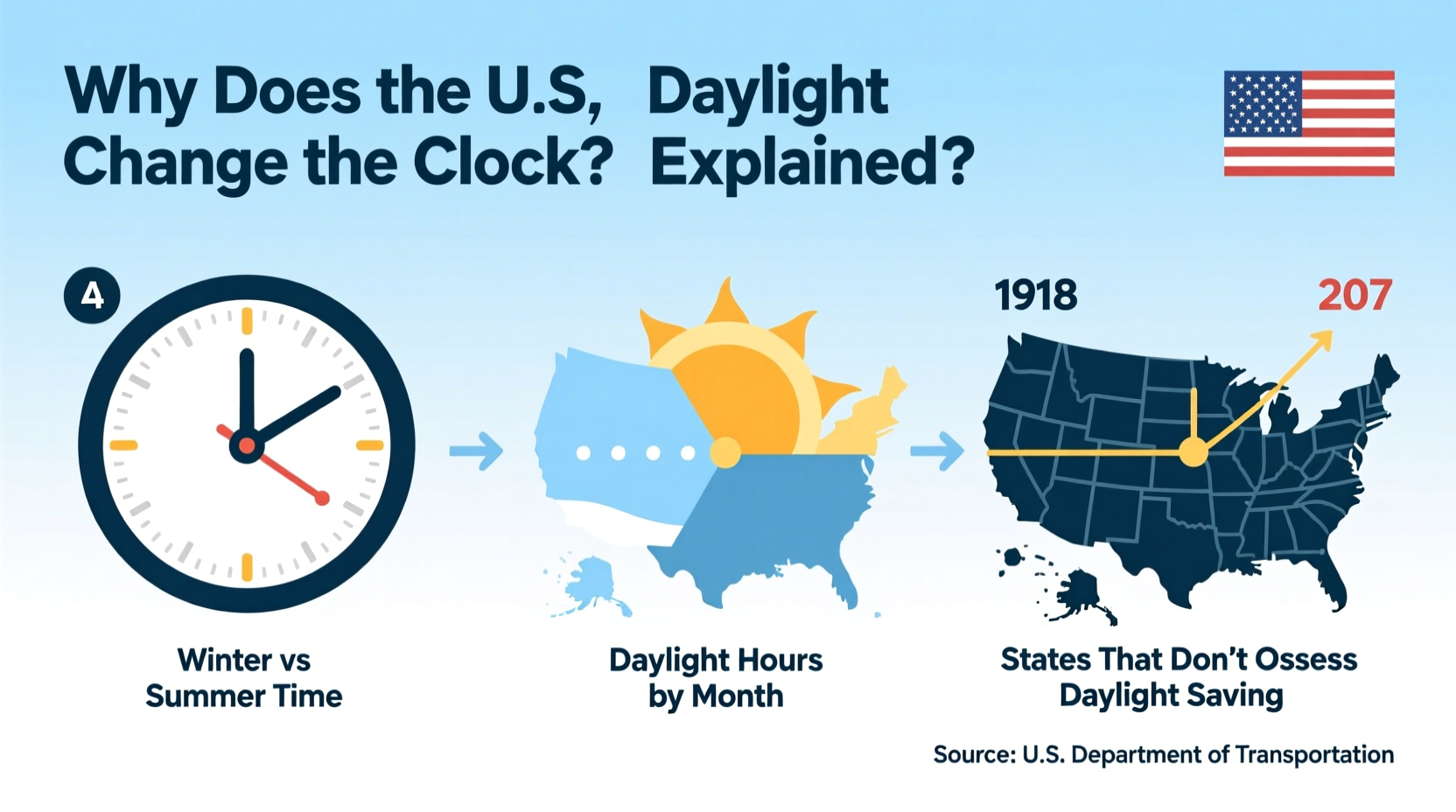

Germany became the first country to implement DST in 1916 during World War I, aiming to conserve coal by reducing artificial lighting needs. The U.S. followed suit in 1918, also during wartime, under the Standard Time Act. After initial resistance and repeal post-war, DST was reintroduced during World War II and eventually standardized nationwide with the Uniform Time Act of 1966.

“We set our clocks not by nature, but by policy. Daylight Saving Time is less about sunlight and more about how societies choose to organize time.” — Dr. David Prerau, Author of *Seize the Daylight*

How Daylight Saving Time Works in the U.S.

Today, most of the United States observes DST according to a federal schedule:

- Clocks “spring forward” one hour at 2:00 a.m. on the second Sunday in March.

- Clocks “fall back” one hour at 2:00 a.m. on the first Sunday in November.

This means Americans lose an hour of sleep in March and gain one in November. The practice affects roughly 48 states, though exceptions exist:

| State/Territory | Observes DST? | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Arizona | No | Except for the Navajo Nation, which does observe DST. |

| Hawaii | No | Never adopted DST due to consistent daylight year-round. |

| Puerto Rico | No | Tropical latitude results in minimal daylight variation. |

| Indiana (historically) | Now Yes | Until 2006, parts of Indiana didn’t observe DST. |

| Mainland U.S. (48 states) | Yes | Follows federal DST schedule. |

Why Does the U.S. Still Change the Clock?

The original justification for DST was energy conservation. By shifting daylight to evening hours, the theory went, people would rely less on electric lighting and reduce fuel consumption. In the 1970s, during the oil crisis, the U.S. extended DST to test this idea. A 1975 Department of Transportation study claimed a slight reduction in electricity use—about 1% per day—but modern studies suggest those savings are negligible today.

Other commonly cited benefits include:

- Increased evening recreation: More daylight after work encourages outdoor activities like walking, biking, and sports.

- Retail and tourism boost: Extended daylight correlates with higher consumer spending in sectors that operate in the evening.

- Safety improvements: Some studies show a modest drop in traffic accidents during evening rush hour when more light is available.

Yet critics argue these advantages are overstated. Modern heating, cooling, and digital devices have changed energy use patterns. Air conditioning in summer evenings may even increase energy demand under DST. Additionally, the time shift disrupts sleep cycles, potentially increasing health risks.

Health and Safety Concerns

Research links the start of DST to short-term spikes in heart attacks, strokes, workplace injuries, and car accidents. A 2020 study published in Open Heart found a 24% increase in acute myocardial infarctions in the week following the spring transition.

The abrupt shift interferes with circadian rhythms, particularly problematic for individuals with existing sleep disorders or mental health conditions. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has called for the elimination of seasonal time changes in favor of permanent standard time, citing better alignment with human biology.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Adjusting to the Time Change

Making a smooth transition twice a year requires preparation. Follow this timeline to minimize disruption:

- One week before: Shift your bedtime and wake-up time by 10–15 minutes daily to gradually align with the new schedule.

- Three days prior: Limit screen exposure after 8 p.m., as blue light delays melatonin production.

- The night before: Go to bed slightly earlier (if springing forward) or allow extra rest (if falling back).

- Morning of: Expose yourself to natural light immediately upon waking to reset your internal clock.

- First week after: Maintain a consistent sleep routine—even on weekends—to stabilize your rhythm.

“Your body doesn’t adjust in one night. Give it time. Think of time changes like jet lag—you wouldn’t fly to Europe and expect to function normally the next day.” — Dr. Rebecca Robbins, Sleep Scientist, Harvard Medical School

Is Daylight Saving Time Ending Soon?

There is growing momentum to end the biannual clock shift. As of 2024, over 30 states have introduced legislation to make DST permanent. The Sunshine Protection Act, first introduced in 2022 and reintroduced in Congress, aims to lock the U.S. into year-round DST—meaning no more falling back in November.

However, permanent DST would require Senate approval and presidential signature. Until then, states cannot unilaterally adopt permanent DST unless granted federal exemption. Arizona and Hawaii remain the only states currently exempt.

Proponents of ending the switch argue it reduces confusion, supports public health, and improves productivity. Opponents warn that permanent DST would mean darker winter mornings, especially in northern states, potentially affecting school children and commuters.

Mini Case Study: Florida’s Push for Permanent DST

In 2018, Florida passed the Sunshine Protection Act at the state level, aiming to keep DST year-round. The move was widely popular among residents who enjoyed longer evening daylight for fishing, dining, and tourism. However, the law remains inactive because it awaits federal approval.

The delay highlights a key challenge: while states can opt out of DST (like Arizona), they cannot adopt permanent DST without congressional action. Florida’s experience underscores the need for national coordination—and fuels debate about whether the current system serves modern life.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do all countries observe Daylight Saving Time?

No. Only about 70 countries worldwide use DST, mostly in North America and Europe. Many equatorial and tropical nations see little daylight variation and do not participate. Major countries like Japan, India, and China do not observe DST.

Who decides when Daylight Saving Time starts and ends?

In the U.S., the Uniform Time Act of 1966 gives the federal government authority over DST timing. The Department of Transportation oversees time zone regulations. States may opt out but cannot create their own schedules.

Does Daylight Saving Time actually save energy?

Early 20th-century studies suggested modest energy savings, but recent research shows little to no benefit. In some regions, DST may increase energy use due to higher air conditioning demand in warmer evenings. The original rationale no longer holds strong under modern usage patterns.

Final Thoughts: Should We Keep Changing the Clock?

Daylight Saving Time began as a wartime efficiency measure, not a biological or societal ideal. Over a century later, its continued use rests more on habit than evidence. While extended evening light has social and economic appeal, the costs in health, safety, and convenience are increasingly hard to ignore.

Whether the U.S. moves toward permanent standard time, permanent DST, or keeps the status quo, one thing is clear: the conversation is far from over. As science, lifestyle, and energy needs evolve, so too must our relationship with time.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?