The United States Congress consists of two chambers: the House of Representatives and the Senate. This structure, known as a bicameral legislature, is not unique to the U.S., but its origins and function are deeply rooted in the nation’s founding principles, compromises, and practical governance needs. Understanding why the U.S. has two legislative houses requires examining history, political theory, and the balance of power between states and citizens.

The Historical Roots of a Bicameral System

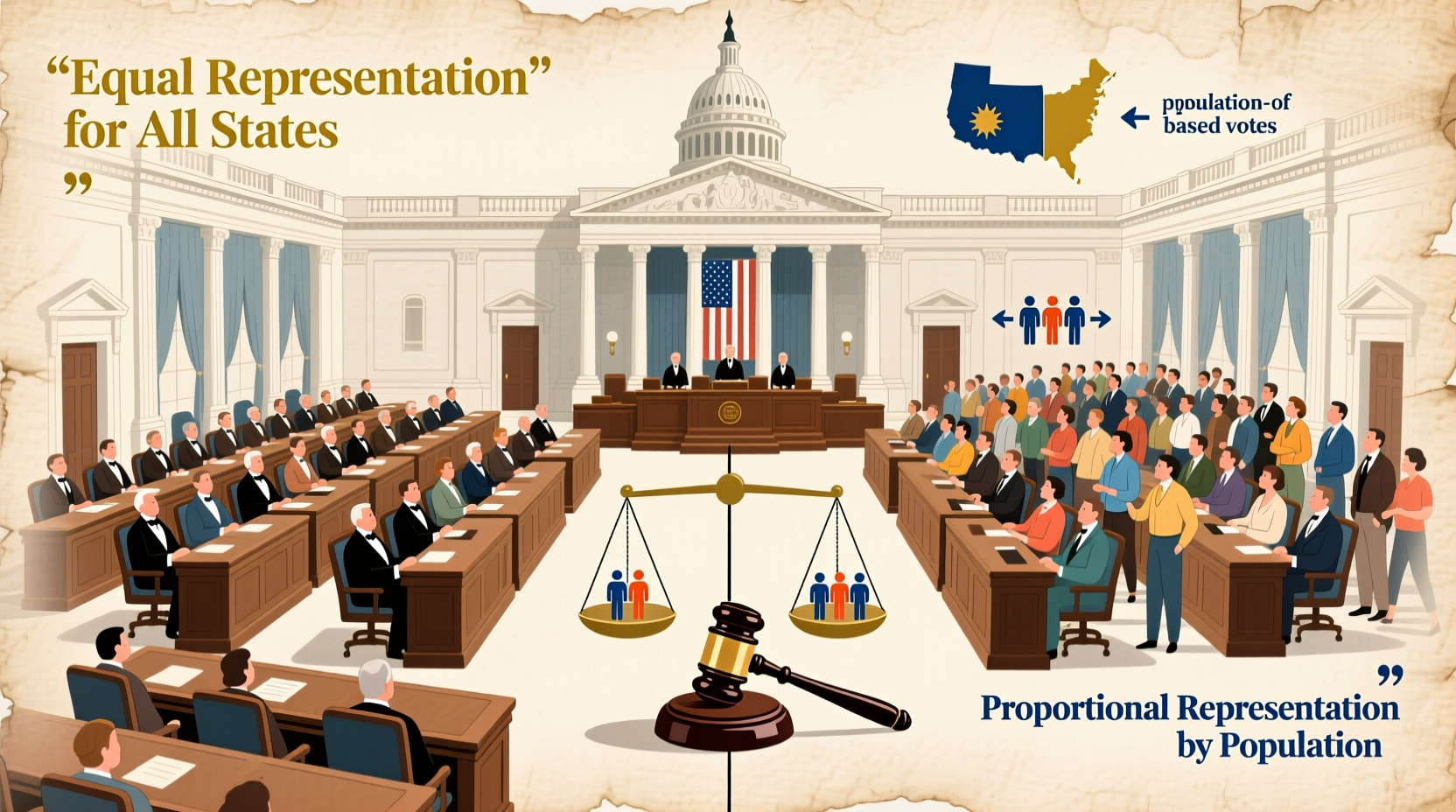

When the Founding Fathers gathered at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, one of their most contentious debates centered on how to structure the national legislature. Delegates from larger states favored representation based on population, while smaller states demanded equal voice regardless of size. This conflict threatened to derail the entire constitutional process.

The solution came in the form of the Great Compromise (also known as the Connecticut Compromise), proposed by Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth. It established a two-house legislature: the House of Representatives, where seats are allocated by population, and the Senate, where each state—regardless of size—gets two senators. This compromise satisfied both large and small states and laid the foundation for the current system.

“We were neither the same nor entirely different; we were united in purpose but diverse in interest. A single house could not fairly represent such a union.” — James Madison, Notes on the Constitutional Convention

Functions and Differences Between the Two Houses

The House and Senate serve distinct roles, reflecting their different methods of election, term lengths, and responsibilities. These differences are intentional, designed to promote deliberation, accountability, and stability.

| Feature | House of Representatives | Senate |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Members | 435 voting members | 100 senators (2 per state) |

| Term Length | 2 years | 6 years |

| Election Basis | Population-based districts | Equal per state |

| Leadership | Speaker of the House | Vice President (as President of the Senate) |

| Exclusive Powers | Initiate revenue bills, impeach officials | Confirm appointments, ratify treaties, conduct impeachment trials |

This division ensures that legislation must pass through two different filters—one more responsive to public opinion, the other designed for longer-term stability and state-level consensus.

Why Two Houses? The Practical and Philosophical Reasons

The decision to create two chambers was not arbitrary. It served multiple purposes:

- Checks within the legislature: By requiring agreement from two differently structured bodies, the system prevents hasty or extreme legislation. One chamber can act as a brake on the other.

- Protection of minority interests: Smaller states gain disproportionate influence in the Senate, ensuring they cannot be overridden by more populous states in every decision.

- Representation of different constituencies: The House represents the people directly through population-based districts. The Senate represents the states as sovereign entities, preserving federalism.

- Stability and continuity: With staggered six-year Senate terms, only one-third of the chamber faces election every two years, providing institutional memory and reducing volatility.

This dual approach reflects Enlightenment-era thinking about balanced government. Drawing from philosophers like Montesquieu, the framers believed that separating powers—and even creating internal legislative checks—would prevent tyranny and promote thoughtful lawmaking.

A Real Example: The Affordable Care Act

The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 illustrates how the two-chamber system operates under pressure. The bill originated in the House, where it passed after intense debate. In the Senate, it required extensive negotiation due to the filibuster rule, which demands 60 votes to end debate on most legislation. Ultimately, changes were made to secure enough support, and a revised version passed. The final law only emerged after both chambers approved identical language—a process that took months.

This example shows how the bicameral system slows down legislation but also forces compromise, especially when control of the two chambers is divided or when narrow majorities exist.

How Legislation Moves Through Both Chambers

For a bill to become law, it must follow a specific path through both houses:

- A member introduces a bill in either the House or Senate.

- The bill is assigned to a committee for review, amendment, or rejection.

- If approved by committee, it goes to the full chamber for debate and vote.

- If passed, it moves to the other chamber and repeats the process.

- If the second chamber passes a different version, a conference committee reconciles the differences.

- Both chambers must approve the final version before sending it to the President.

This process ensures thorough scrutiny. However, it also contributes to legislative delays, especially when partisan divisions exist between the chambers.

Common Criticisms and Ongoing Debates

While the two-house system has endured for over two centuries, it is not without criticism. Some argue that the Senate’s equal representation gives disproportionate power to less populous states. For instance, Wyoming (population ~580,000) has the same Senate representation as California (~39 million). Critics say this undermines democratic equality.

Others point to the Senate’s rules—like the filibuster—as obstacles to effective governance. Because most bills require 60 votes to advance, a minority can block legislation supported by a simple majority.

Despite these concerns, defenders maintain that the Senate’s design protects federalism and prevents rapid policy swings driven by temporary majorities. As political scientist Dr. Lisa Stevens notes:

“The Senate isn’t meant to be fast. It’s meant to be deliberate. Its slowness is not a bug—it’s a feature designed to protect long-term national interests.” — Dr. Lisa Stevens, Government & Institutions Scholar

Frequently Asked Questions

Why didn’t the U.S. adopt a one-house legislature?

A unicameral system was considered but rejected during the Constitutional Convention. The framers feared that a single legislative body could become too powerful or too easily swayed by public emotion. They believed a second chamber would provide necessary oversight and cooling-off time for legislation.

Can a bill start in the Senate?

Yes, most bills can originate in either chamber—except for revenue bills, which the Constitution requires to begin in the House of Representatives. This rule stems from the principle that taxes should be closest to the people, who elect House members every two years.

Has any state tried a unicameral legislature?

Yes. Nebraska is the only U.S. state with a unicameral legislature. Adopted in 1937, it was intended to reduce costs and increase efficiency. While it functions well for a smaller state government, scaling this model to the national level remains a subject of debate.

Conclusion: The Enduring Value of a Bicameral Congress

The U.S. Congress has two houses because the nation’s founders sought balance—between large and small states, between popular will and stable governance, and between swift action and careful deliberation. The bicameral system is not always efficient, but its complexity is by design. It forces negotiation, tempers extremism, and upholds the federal structure of the United States.

Understanding this structure helps citizens engage more thoughtfully with the legislative process, appreciate the role of compromise, and recognize why some laws take years to pass. In a democracy, progress often requires patience.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?