It’s a common refrain heard across generations: “Where did the year go?” or “I can’t believe how fast time is passing.” As children, a summer vacation felt endless; now, entire seasons blur into one another. This subjective acceleration of time isn’t an illusion—it’s a well-documented psychological phenomenon. Scientists, philosophers, and neurologists have spent decades exploring why time seems to accelerate with age. The answer lies not in the clock, but in how our brains perceive and process the passage of time.

Unlike physical time, which ticks forward at a constant rate, psychological time is malleable—shaped by memory, routine, novelty, and attention. As we grow older, changes in these cognitive processes alter our experience of duration. Understanding this shift offers more than just intellectual curiosity; it empowers us to reclaim a sense of presence and depth in our daily lives.

The Proportional Theory: A Mathematical View of Time

One of the oldest explanations for time’s apparent acceleration comes from 19th-century philosopher Paul Janet, whose idea is now known as the \"proportional theory.\" According to this model, each passing year represents a smaller fraction of your total life. When you're five years old, one year is 20% of your entire existence. By age 50, that same year is only 2% of your life. This shrinking proportion makes each unit of time feel relatively shorter.

This logarithmic perception means that early experiences carry greater emotional and cognitive weight. Childhood milestones—your first day of school, learning to ride a bike—are remembered vividly because they represent large portions of your lived experience. In contrast, adult years, filled with repetition and fewer firsts, fade into the background.

“Each new year becomes a smaller fraction of what we’ve already lived, making it feel fleeting in comparison.” — Dr. William Friedman, Cognitive Psychologist

While simplistic, the proportional theory aligns with both anecdotal evidence and mathematical models of human perception. It doesn’t require complex neuroscience to grasp—just a recognition that context shapes experience.

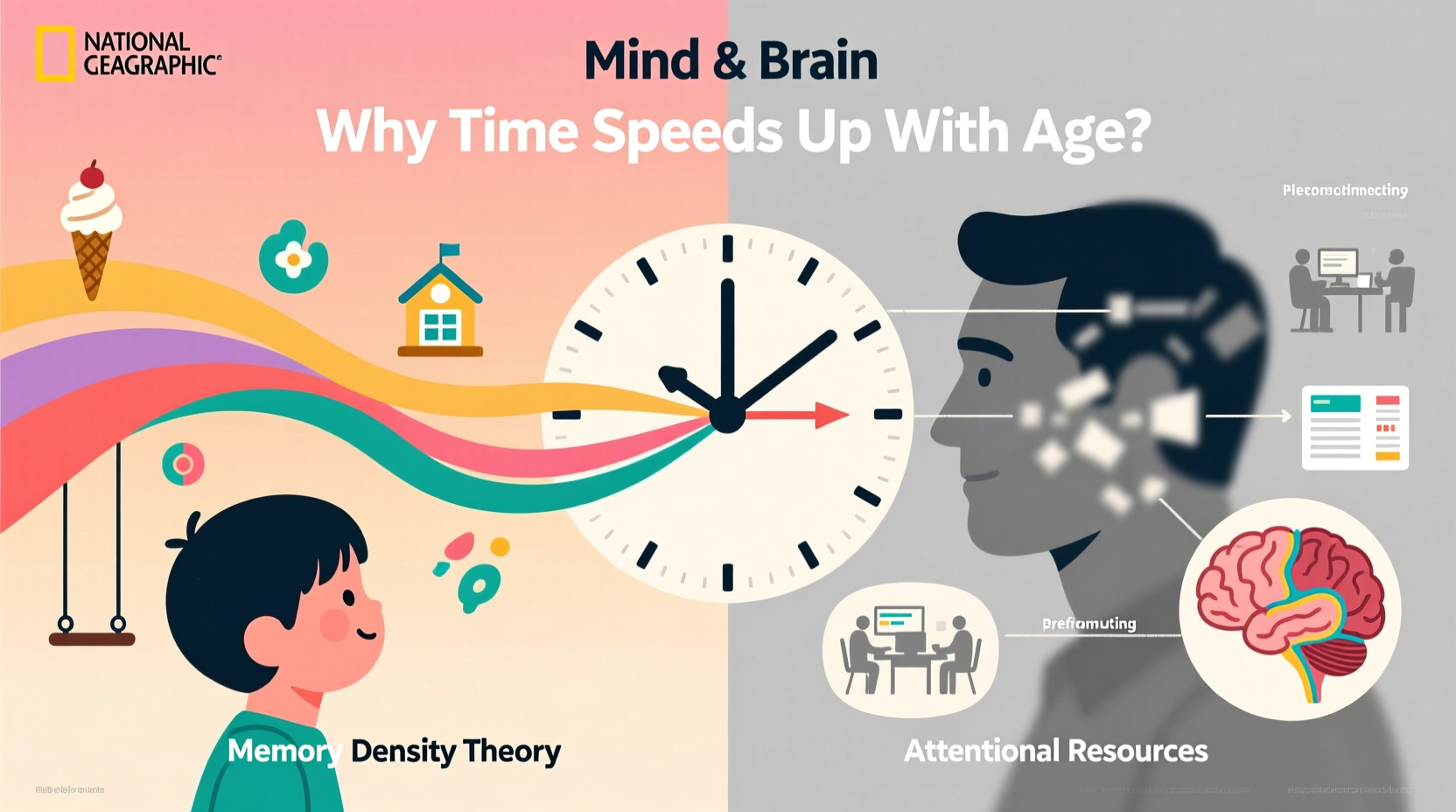

Memory Density and Novelty: Why New Experiences Slow Time

Another compelling explanation involves memory formation. Our perception of time is closely tied to how many new memories we encode. Periods rich in novel experiences—traveling to a new country, starting a new job, falling in love—feel longer in retrospect because they leave behind dense clusters of memories. Routine, on the other hand, creates memory gaps.

Children live in a constant state of discovery. Every season brings new skills, environments, and social interactions. Their brains are in high-gear, absorbing and storing information. Adults, especially after settling into careers and family life, fall into predictable patterns. Commuting, working, eating the same meals—these activities don’t demand much cognitive effort or create strong memory markers.

As a result, when looking back, adults often find that months or even years seem to vanish. There’s little to anchor them in memory. The brain compresses time during periods of low novelty, creating the sensation that it “flew by.”

Biological Clocks and Neural Processing Speed

Beyond psychology, biological factors may influence our internal timekeeping. Some researchers suggest that our perception of time is regulated by internal physiological rhythms—heart rate, breathing, metabolic activity—all of which tend to slow with age.

In youth, higher metabolic rates and faster heartbeats may lead to more “time stamps” being processed per second. Think of it like a camera recording at 60 frames per second versus 30. The higher frame rate captures more detail, making events feel longer when played back. Similarly, a child’s rapidly firing neurons might generate a denser stream of conscious moments, stretching perceived duration.

A 2007 study published in *Neuropsychologia* found that younger participants were better at estimating short intervals (e.g., 3 minutes) than older adults, who consistently underestimated elapsed time. This suggests that the brain’s internal clock may literally slow down over time, causing external events to appear to pass more quickly.

Additionally, dopamine levels decline with age. Since dopamine plays a role in attention and time perception, reduced levels could impair the brain’s ability to track duration accurately. Medications that affect dopamine, such as those used for Parkinson’s disease, have been shown to distort time estimation, further supporting this link.

Attention and Mindfulness: How Focus Alters Time

Where we direct our attention significantly impacts how we experience time. When deeply focused—on a conversation, a creative task, or a sporting event—time seems to vanish. Conversely, when bored or waiting, time drags. This is known as the “attentional gate model,” where the amount of attention allocated to time itself determines its perceived length.

Adults are often mentally divided—juggling work deadlines, parenting duties, financial planning—leaving little room for present-moment awareness. We operate on autopilot, checking off tasks without full engagement. This lack of mindfulness contributes to the feeling that days blend together.

In contrast, mindfulness practices—such as meditation, journaling, or simply paying attention to sensory details—can slow down subjective time. By increasing awareness of the present, these habits enrich our memory of the moment and make time feel fuller.

| Life Stage | Typical Time Perception | Main Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Childhood (0–12) | Time feels long and expansive | High novelty, rapid learning, dense memory encoding |

| Adolescence (13–19) | Mixed—some years drag, others fly | Emotional intensity, identity formation, social change |

| Young Adulthood (20–35) | Time begins to accelerate | Establishing routines, career focus, fewer “firsts” |

| Middle Age (36–60) | Time feels increasingly fast | Routine dominance, reduced novelty, family/work demands |

| Later Life (60+) | Years pass in a flash | Retirement, health concerns, reflection on past |

Mini Case Study: Reclaiming Time Through Intentionality

Sarah, a 48-year-old project manager, began noticing how quickly the years passed. Birthdays came and went without fanfare. Her daughter graduated high school, and she couldn’t recall the last three summers clearly. Worried about losing touch with her own life, Sarah decided to experiment.

She started small: taking a different route to work once a week, scheduling monthly solo outings to museums or nature trails, and keeping a weekly journal. She also practiced mindful walking—focusing on her breath and surroundings instead of scrolling through emails.

Within six months, she reported a noticeable shift. Time didn’t speed up or slow down objectively, but her memory of the period was richer. She could recall specific conversations, sunsets, and personal insights. “It’s not that more happened,” she said, “but I feel like I was actually there for it.”

Sarah’s experience illustrates that while we can’t stop aging, we can influence how we remember and experience time through deliberate choices.

Actionable Strategies to Slow Down Your Perception of Time

You don’t need radical lifestyle changes to regain a sense of temporal depth. Small, consistent actions can reshape your relationship with time. Here’s a checklist to help you get started:

- Seek novelty regularly: Try new foods, visit unfamiliar places, take up a hobby.

- Break routines intentionally: Change your morning sequence, rearrange your workspace.

- Practice mindfulness: Spend 5–10 minutes daily focusing on your breath or surroundings.

- Keep a journal: Write down meaningful moments, no matter how small.

- Limits screen time: Constant digital stimulation fragments attention and dulls memory.

- Engage deeply in conversations: Listen fully instead of thinking about your next response.

- Reflect weekly: Review your week and identify memorable moments.

“The key to slowing time isn’t doing more—it’s experiencing more fully.” — Dr. Claire Silver, Behavioral Scientist

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do vacations feel long while happening but short in memory?

Vacations often feel long in the moment due to heightened attention and new stimuli. However, if they lack unique or emotionally significant events, they may not form strong memory traces. Upon return, without distinct anchors, the trip can seem to have passed quickly in retrospect.

Can trauma affect time perception?

Yes. During traumatic events, the brain enters hyper-alert mode, increasing sensory processing and memory encoding. This can make the event feel like it lasted much longer than it did—a phenomenon known as \"time dilation.\" Flashbacks and PTSD often involve vivid, slow-motion recollections of brief moments.

Is it possible to reverse the feeling that time is speeding up?

While we can’t stop aging, we can counteract the feeling of acceleration. Introducing novelty, practicing mindfulness, and reflecting on experiences strengthen memory density and increase the richness of our temporal experience. People who maintain curiosity and engagement often report a more balanced sense of time, regardless of age.

Conclusion: Living More by Feeling Time Differently

The sensation that time accelerates with age is not inevitable—it’s a product of habit, biology, and attention. By understanding the mechanisms behind this phenomenon, we gain the power to reshape our experience. Time cannot be extended, but it can be deepened.

Every moment holds the potential for novelty, connection, and presence. Whether it’s savoring a morning coffee without distraction, learning something new, or simply pausing to notice the light through the trees, these acts build memory and meaning. They don’t add years to life, but they add life to years.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?