Most people reach a point in life—often in their 30s or 40s—when they begin to notice something unsettling: years seem to vanish almost overnight. Birthdays arrive with alarming speed, holidays blur together, and entire seasons pass without leaving much of an imprint. This isn’t just nostalgia or sentimentality. There’s a growing body of scientific research explaining why time feels like it accelerates with age. The phenomenon is rooted not in physics, but in psychology, neurology, and the way our brains process memory and novelty.

The sensation that time moves faster as we grow older is nearly universal. Children often complain that summer vacation can't come fast enough, yet when they're in it, each day stretches endlessly. By contrast, adults frequently remark how January feels like yesterday, even as December looms. Understanding this shift requires examining how perception, routine, and cognitive development interact across the lifespan.

The Proportional Theory: A Mathematical View of Time

One of the earliest explanations for time's apparent acceleration comes from 19th-century philosopher Paul Janet, who proposed what is now known as the “proportional theory.” According to this idea, each passing year represents a smaller fraction of your total life. When you’re five years old, one year is 20% of your existence. That’s a massive proportion—no wonder it feels long. But at 50, a single year is just 2% of your life. Mathematically, it makes sense that it would subjectively feel shorter.

This theory doesn’t rely on memory or brain chemistry—it’s purely perceptual. Your mind may be subconsciously comparing new experiences to the totality of what you’ve lived through. As that total grows, new slices of time become proportionally smaller, making them feel fleeting.

While elegant, the proportional theory has limitations. It assumes consistent perception, which neuroscience shows isn’t the case. Still, it offers a foundational framework: time doesn’t change, but our relationship to it does.

Neurological Changes and Cognitive Load

As we age, structural and functional changes in the brain influence how we perceive duration. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), located in the hypothalamus, regulates circadian rhythms and internal timekeeping. Over decades, neural firing rates in this region—and others involved in attention and memory—can decline.

Additionally, dopamine levels decrease with age. Dopamine plays a key role in the brain’s internal clock. Studies show that higher dopamine activity correlates with a slower subjective sense of time. Children, who have rapidly firing dopamine systems due to constant learning and exploration, may literally experience time more slowly. As dopamine production stabilizes and declines in adulthood, the internal metronome speeds up.

Cognitive load also affects time perception. When the brain is processing large amounts of new information—such as during travel, learning, or emotional events—time seems to slow down. This is why accidents or emergencies often feel like they unfold in slow motion. In contrast, routine reduces cognitive demand. An average Tuesday commute requires little attention, so the brain compresses the experience into a brief memory—or none at all.

The Role of Memory and Novelty

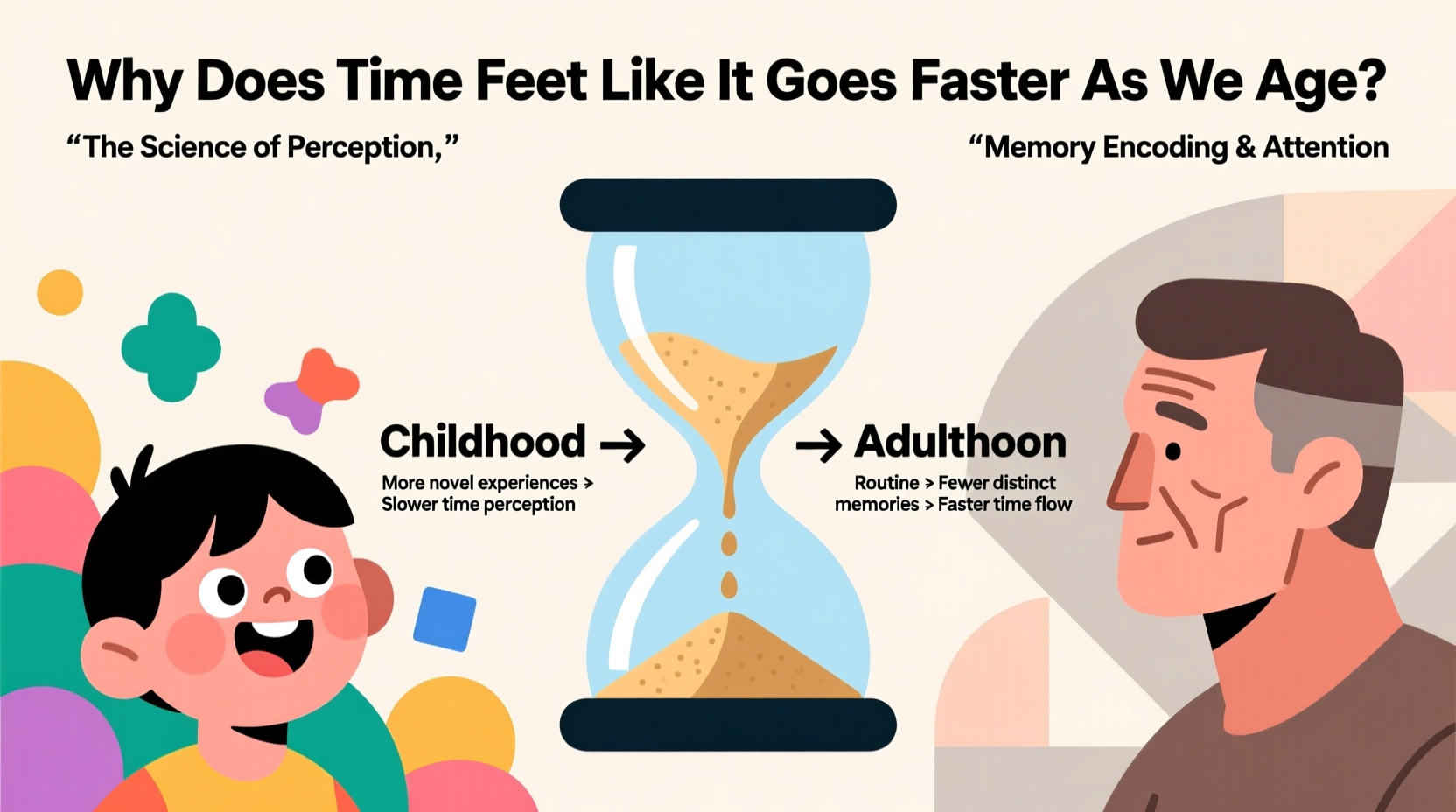

Perhaps the most compelling explanation for time’s acceleration lies in memory formation. Our sense of how long a period lasted is heavily influenced by how many new memories were formed during it. Periods rich in novel experiences—first jobs, college, travel, parenthood—are packed with distinct, emotionally charged memories. These create dense mental timelines that, upon reflection, make those years feel longer.

Adult life, especially after age 30, tends to settle into predictable patterns. Work schedules, family routines, and familiar environments reduce the number of unique experiences. Fewer new memories mean fewer \"bookmarks\" in time. When you look back on a year of repetition, there’s little to distinguish one month from another. The result? A feeling that the year vanished.

Psychologists refer to this as the “holiday paradox.” A two-week trip abroad feels incredibly long while it’s happening due to constant novelty. Yet, months later, it occupies a large space in memory. Meanwhile, six months of routine work might collapse into a single vague recollection: “Yeah, I went to the office, did my job.”

“Time appears to pass quickly not because we age, but because we stop noticing. The richness of time is measured in moments remembered, not seconds elapsed.” — Dr. Laura Simmons, Cognitive Psychologist, University of Edinburgh

Strategies to Slow Down Your Perception of Time

You can’t reverse aging, but you can reshape how you experience time. By intentionally increasing novelty, mindfulness, and memory encoding, you can counteract the brain’s tendency to compress familiar periods. Here are actionable strategies grounded in psychological research:

1. Seek Novel Experiences Regularly

The brain marks time through difference. Doing new things—learning an instrument, visiting unfamiliar places, meeting new people—forces the brain to form detailed memories. Even small changes help. Try a new restaurant, walk in a different park, or read outside your usual genre.

2. Practice Mindful Awareness

Mindfulness meditation trains attention and deepens sensory awareness. When you pay close attention to the present moment—the taste of coffee, the sound of rain, the rhythm of breathing—you create richer memories. These serve as anchors when looking back, giving the past more texture and depth.

3. Keep a Journal or Photo Log

Writing about your days, even briefly, strengthens memory retention. Reviewing entries months later reveals how much actually happened, countering the illusion of time loss. Photos serve a similar function, though passive scrolling is less effective than active reflection.

4. Break Routines Strategically

Routines are efficient but memory-poor. Disrupt automatic behaviors occasionally. Work from a café, switch your workout schedule, or plan spontaneous outings. The goal isn’t chaos, but variation that signals to your brain: “This matters. Remember this.”

5. Learn Continuously

Learning forces focus and creates new neural pathways. Whether studying a language, taking an online course, or mastering a craft, the effort required slows subjective time. Children seem to live in slow motion partly because everything is new and being learned for the first time.

Mini Case Study: Reclaiming a Year Through Novelty

Mark, a 47-year-old accountant from Portland, noticed that his last few years had blurred into a haze of tax seasons and school pickups. “I’d blink and Christmas was here again,” he said. Concerned, he decided to experiment. He committed to trying one new activity per month for a year: kayaking, pottery class, a solo hiking trip, a silent retreat, and volunteering at an animal shelter.

At year’s end, Mark didn’t just feel more energized—he genuinely felt like he had lived a fuller, longer year. When asked to reflect, he could recall specific moments from each month. “I remember the smell of wet clay, the silence at dawn on the mountain, the dog that followed me around the shelter. Those aren’t just dates on a calendar.”

His experience aligns with research: intentional novelty increases episodic memory density, which elongates retrospective time. For Mark, the year didn’t pass faster—it passed meaningfully.

Do’s and Don’ts of Time Perception Management

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Introduce small surprises into your week | Live entirely on autopilot |

| Practice mindfulness or meditation regularly | Constantly multitask without presence |

| Keep a journal or memory log | Assume busyness equals meaningfulness |

| Learn new skills throughout life | Stop challenging your brain after formal education |

| Take breaks from digital distractions | Spend hours scrolling without awareness |

Frequently Asked Questions

Does stress affect how fast time feels?

Yes. Chronic stress narrows attention and impairs memory formation. When under pressure, people often report that time both drags in the moment and disappears in retrospect. This paradox occurs because stress heightens immediate awareness (making minutes feel long) but overwhelms the brain’s ability to store coherent memories (making weeks feel short).

Can medications alter time perception?

Certain drugs—including stimulants, sedatives, and psychedelics—can dramatically distort time perception. Stimulants like caffeine or amphetamines may speed up the internal clock, making external events seem slower. Conversely, depressants like alcohol can slow cognitive processing, leading to time compression. Always consult a physician before altering medication for non-medical reasons.

Is there a biological \"peak\" for time perception?

There’s no definitive peak, but research suggests that between ages 10 and 15, humans form the highest density of lasting memories—a phenomenon called “reminiscence bump.” This period overlaps with major life transitions, identity formation, and intense learning, all of which enhance memory encoding. As a result, many people recall adolescence with exceptional clarity, contributing to the feeling that life slowed down during those years.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Time Through Attention

Time doesn’t actually speed up. What changes is how we engage with it. Childhood feels longer because everything is new, unfiltered, and deeply observed. Adulthood, with its routines and responsibilities, risks becoming a series of repeated loops with few distinguishing features. But this isn’t inevitable.

By cultivating curiosity, embracing discomfort, and paying deliberate attention, you can restore richness to your experience of time. You don’t need grand gestures—just small acts of presence, learning, and variation. Each new memory you form becomes a foothold against the rush of years.

The goal isn’t to stop aging, but to ensure that when you look back, you see a life fully lived—not one that slipped away.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?