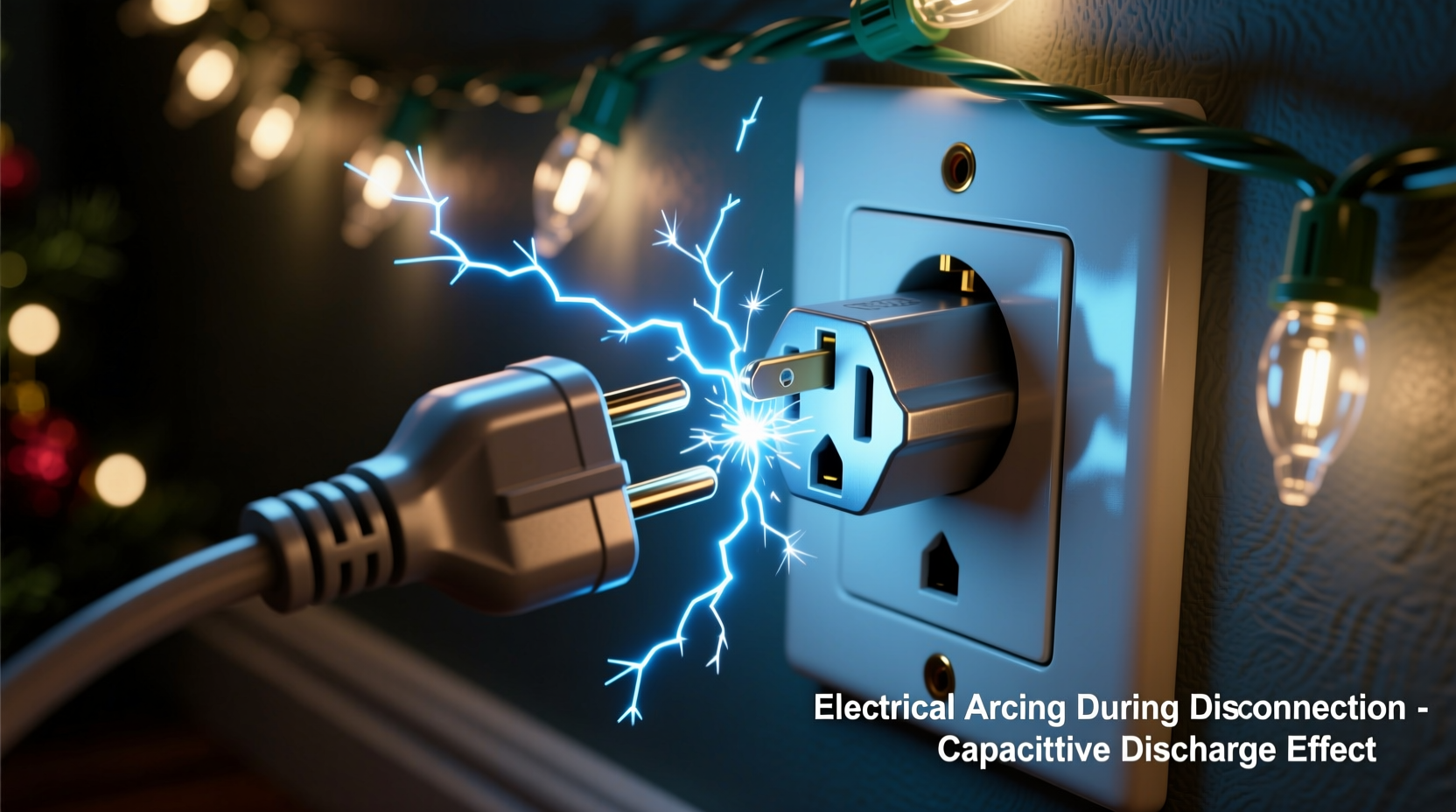

That brief, blue-white flash you see—and sometimes hear—as you yank the plug from the wall socket while your holiday lights are still glowing isn’t imagination or faulty wiring alone. It’s electricity behaving exactly as physics predicts. While most people dismiss it as harmless “static” or “just how lights are,” this phenomenon sits at the intersection of fundamental electromagnetic principles, real-world circuit design, and tangible household safety risks. Understanding why it happens—and when it signals something more serious—is essential for anyone decorating with string lights, especially in homes with older wiring, children, pets, or flammable décor.

The Physics Behind the Spark: It’s All About Inductance and Current Interruption

Christmas light strings—especially incandescent and many LED sets with built-in transformers or rectifiers—contain components that store energy in magnetic fields. When current flows through a wire coil (like those inside power adapters, dimmer circuits, or even the internal windings of some LED drivers), it creates an inductor. Inductors resist changes in current flow. So when you abruptly disconnect power by pulling the plug, the current doesn’t stop instantly—it tries to keep flowing. The collapsing magnetic field converts stored energy into a brief high-voltage surge across the opening contacts of the plug.

This voltage spike can exceed 100–300 volts momentarily—even if the circuit operates at only 120 V AC—sufficient to ionize the tiny air gap between the plug’s prongs and the socket’s metal contacts. Ionized air becomes conductive, allowing a miniature arc: the visible spark. It lasts microseconds, but it’s real, measurable, and repeatable under load.

Crucially, the spark is far more likely when the lights are *on* and drawing current. If the switch on the cord or the outlet is turned off first—cutting current before physical disconnection—the spark is nearly eliminated. That distinction matters deeply for both safety and longevity.

Why Some Lights Spark More Than Others

Not all light strings behave identically. Spark intensity and frequency depend on three interrelated factors: circuit topology, load type, and power delivery method. Here’s how common configurations compare:

| Light Type | Likelihood of Sparking | Primary Reason | Safety Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Incandescent Mini-Lights (Series-Wired) | Moderate | Low inductance, but high inrush current when cold filament heats rapidly; arcing occurs mainly at plug due to mechanical interruption | Low (but repeated sparking degrades contacts) |

| LED Lights with AC/DC Adapter (Wall-Wart Style) | High | Adapter contains transformer + rectifier + smoothing capacitor—significant inductive and capacitive energy storage; abrupt disconnection releases stored energy violently | Moderate (capacitor discharge can stress outlet contacts over time) |

| LED Lights with Integrated Driver (No External Adapter) | High to Very High | Often include active switching regulators and EMI filters with chokes and capacitors—designed for efficiency, not plug-pull resilience | Moderate–High (repeated arcing accelerates oxidation and pitting) |

| Battery-Powered LED Strings | Negligible | No mains connection; no sustained current flow to interrupt | None |

| Smart Lights with Wi-Fi/Zigbee Modules | Very High | Multiple power conversion stages, standby circuits, and communication chips retain microcurrents; complex impedance profiles increase transient sensitivity | Moderate (potential for cumulative contact damage and fire hazard in compromised outlets) |

Note: Vintage or damaged cords—especially those with frayed insulation, corroded prongs, or loose internal connections—amplify sparking due to increased resistance and inconsistent contact separation. A spark that used to be faint may become louder, brighter, or accompanied by a burning smell: clear warning signs.

Real-World Implication: When a Spark Stops Being Normal

Consider the case of Maria R., a schoolteacher in Portland, Oregon, who decorated her century-old home each November for over fifteen years. In December 2022, she noticed her outdoor LED icicle lights produced an unusually loud “snap” and visible 5-mm arc each time she unplugged them—even after turning off the outdoor GFCI breaker. She dismissed it until the plug’s brass prongs developed black scorch marks and the outlet faceplate felt warm to the touch. An electrician found two issues: (1) the GFCI was failing internally—allowing residual current to linger—and (2) the outlet’s screw terminals were corroded, increasing resistance and heat buildup during arcing. Replacing both the GFCI and the outlet resolved the problem. Her experience underscores a critical truth: a spark isn’t inherently dangerous—but its evolution *is* diagnostic.

According to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), electrical distribution and lighting equipment accounted for an estimated 19,700 home structure fires annually (2018–2022 data), with faulty cords and outlets contributing to nearly 12% of those incidents. While most holiday-light-related fires stem from overheating or overloading—not sparking alone—the cumulative effect of repeated arcing degrades metal contacts, increases resistance, and raises localized temperatures. That degradation creates a feedback loop: more resistance → more heat → more oxidation → poorer contact → larger sparks → more heat.

“Every time you unplug under load, you’re performing a micro-welding operation in reverse—burning away microscopic layers of metal. Do it hundreds of times, and you’ve essentially sandblasted your outlet’s integrity.” — Dr. Lena Cho, Electrical Engineering Professor, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, author of *Practical Electromagnetics for Home Systems*

7 Actionable Safety Tips to Prevent Hazardous Sparking

- Use switched outlets or power strips: Plug lights into a strip with a clearly labeled, easily accessible toggle switch. Flip it off first—then unplug.

- Inspect plugs and outlets quarterly: Look for discoloration (brown/black marks), melted plastic, warmth, or loose fit. Replace any component showing these signs immediately.

- Avoid daisy-chaining power strips: Each added connection point multiplies resistance and potential failure points. Plug directly into a wall outlet—or use one high-quality, UL-listed strip rated for your total load.

- Unplug gently and steadily: Yanking creates faster contact separation, increasing peak voltage across the gap. A slow, firm withdrawal reduces spark intensity.

- Choose lights with “soft-start” or “zero-crossing” circuitry: Higher-end commercial or professional-grade LED strings incorporate controllers that cut power precisely when AC voltage crosses zero—minimizing inductive kickback.

- Install AFCI/GFCI protection: Arc-Fault Circuit Interrupters detect dangerous arcing patterns (including sustained or high-energy arcs) and shut off power within milliseconds. Required by NEC in most new residential circuits since 2014.

- Retire cords older than 5 years: PVC insulation becomes brittle, copper oxidizes, and strain relief degrades. Even if they “still work,” their safe spark tolerance has diminished.

Step-by-Step: How to Safely Decommission Holiday Lights Without Sparking

- Verify the lights are illuminated — Confirm they’re powered and drawing current (so you know interruption matters).

- Locate and operate the nearest switch — This could be a wall switch controlling the outlet, the GFCI test/reset button, or the switch on your power strip. Press or flip it to the OFF position. Wait 3 seconds.

- Confirm power is off — Check that lights go dark. If using a multimeter, verify 0 V AC at the plug’s prongs (optional but definitive).

- Grip the plug firmly by its insulated body — Never pull by the cord. Position your thumb and forefinger around the plug’s plastic housing.

- Withdraw steadily and perpendicularly — Apply even pressure straight out from the socket. Avoid twisting or angling, which can scrape contacts and increase friction-induced heat.

- Inspect the plug and outlet — Before storing, examine both for scorch marks, debris, or bent prongs. Clean metal contacts with isopropyl alcohol and a soft cloth if lightly tarnished.

- Store coiled loosely in climate-controlled space — Avoid tight wraps or plastic bags, which trap moisture and accelerate corrosion.

FAQ: Addressing Common Concerns

Is a tiny spark when unplugging ever completely safe?

Yes—if it’s consistently faint (barely visible in daylight), silent or faintly hissing, occurs only when lights are on, and leaves no residue or odor. It reflects normal inductive behavior in low-power (<50W) loads. However, safety isn’t binary: repeated occurrences accelerate wear. Treat even “normal” sparking as a prompt to adopt safer disconnection habits—not as permission to ignore it.

Can sparking damage my lights or outlet over time?

Absolutely. Each spark vaporizes nanograms of copper and nickel from both plug and socket contacts. Over dozens of cycles, this creates microscopic pits and carbon deposits, increasing electrical resistance. Higher resistance means more heat during operation—a leading cause of outlet failure, melting, and fire ignition. UL testing shows standard residential outlets degrade significantly after ~500 load-interruption cycles without switching; smart switches extend that to 10,000+.

Why do newer LED lights seem to spark more than old incandescent strings?

It’s not the LEDs themselves—it’s the supporting electronics. Modern LED strings require precise DC voltage regulation. Their drivers contain high-frequency switching transistors, ferrite chokes, and electrolytic capacitors—all of which store energy and react strongly to sudden current cutoff. Incandescents are purely resistive loads with minimal stored energy, making them inherently less prone to energetic arcing.

Conclusion: Respect the Spark—Then Eliminate It

A spark is electricity’s way of saying, “I wasn’t ready to stop.” It’s a visible reminder that our holiday traditions interface with powerful physical forces—forces we can neither ignore nor wish away, but which we absolutely can manage with knowledge and intention. Unplugging lights shouldn’t be a reflexive tug at a cord; it should be a deliberate, two-step safety protocol: break the circuit first, then break the connection. That small pause—three seconds to flip a switch—preserves your outlets, extends the life of your lights, protects your home, and models mindful energy use for everyone in your household.

This isn’t about fear—it’s about fluency. Fluency in how electricity moves, stores, and releases energy empowers better decisions, prevents costly repairs, and transforms seasonal decoration from a potential hazard into a calm, controlled ritual. Start this year: add a labeled switch to your main light outlet, inspect every plug before hanging, and teach your family the two-step disconnect. Your future self—and your home’s electrical system—will thank you.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?