If you’ve ever shaken a bottle of salad dressing or watched rain fall through motor oil in a puddle, you’ve seen oil and water refuse to blend. Despite vigorous mixing, they always separate. This common observation has deep roots in chemistry and physics. The reason oil and water don’t mix isn’t magic—it’s molecules behaving according to fundamental scientific principles. Understanding this phenomenon doesn’t require a lab coat, just a curiosity about how the world works at the smallest scale.

The Role of Molecular Polarity

All matter is made of molecules, and how those molecules interact depends largely on their electrical charge distribution. Water (H₂O) is a polar molecule. This means it has an uneven distribution of electrons: the oxygen atom pulls more strongly on shared electrons than the hydrogen atoms do. As a result, the oxygen end carries a slight negative charge, while the hydrogen ends are slightly positive.

This polarity allows water molecules to form strong attractions with each other—what scientists call hydrogen bonds. These bonds are responsible for many of water’s unique properties, including its high boiling point and surface tension.

In contrast, most oils are nonpolar. They’re typically long chains of carbon and hydrogen atoms (like hydrocarbons), where electrons are shared almost equally. Without regions of strong positive or negative charge, nonpolar molecules can’t form hydrogen bonds. Instead, they interact through much weaker dispersion forces.

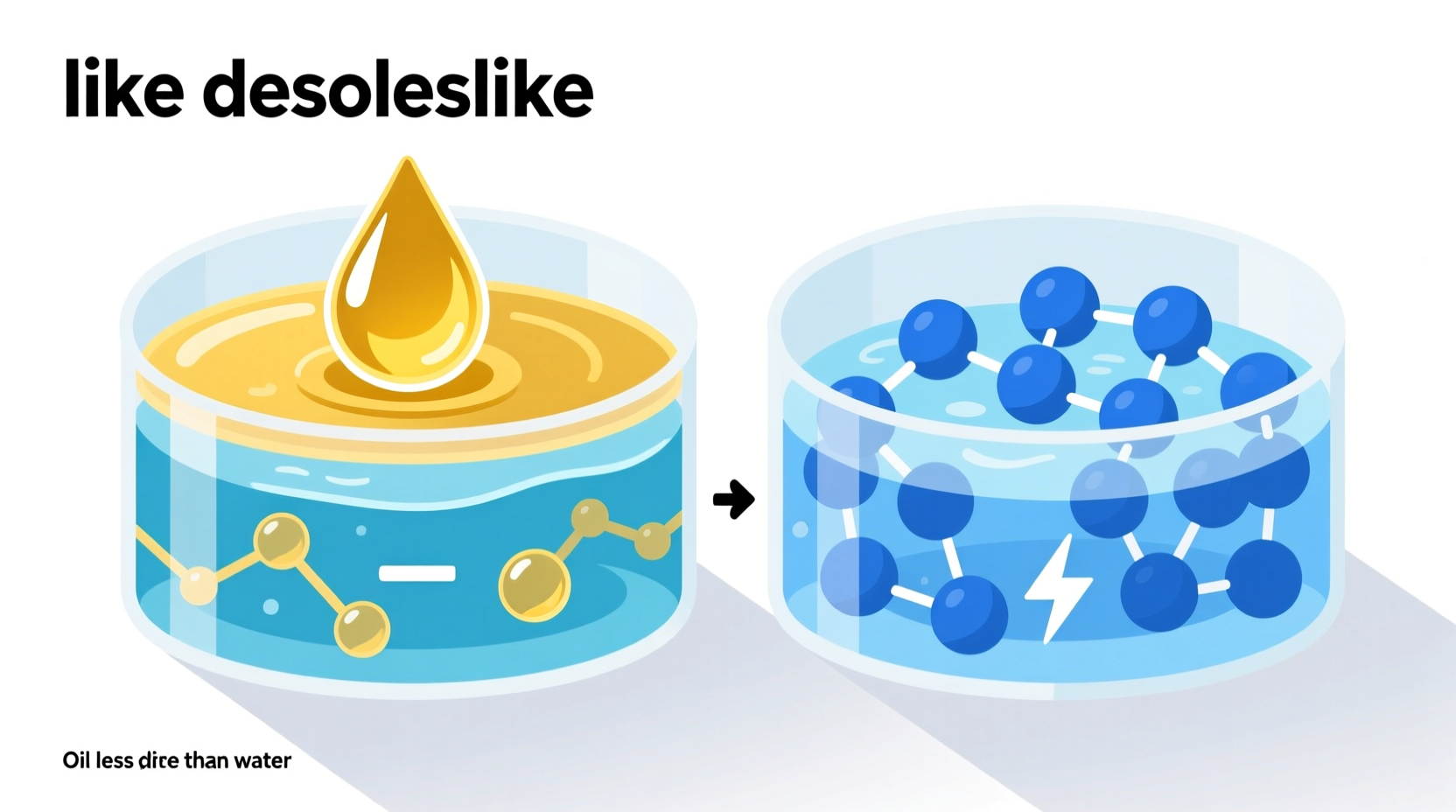

Like Dissolves Like: The Solubility Principle

One of the foundational rules in chemistry is “like dissolves like.” Polar substances dissolve well in polar solvents (like salt in water), and nonpolar substances dissolve in nonpolar solvents (like grease in gasoline). When you try to mix oil (nonpolar) with water (polar), the two liquids resist blending because their molecular personalities clash.

Water molecules prefer to stick tightly to one another, excluding oil molecules from their network. Meanwhile, oil molecules cluster together to minimize contact with the hostile, polar environment. This mutual rejection leads to phase separation—the formation of distinct layers.

The energy required to break water’s hydrogen bonding network to accommodate oil molecules is not offset by any favorable interactions. In thermodynamic terms, the process is not spontaneous because it increases the system’s overall energy without providing stability.

Intermolecular Forces at Work

To understand why the mixture fails, consider the types of intermolecular forces involved:

- Hydrogen bonding – Strong attraction between polar molecules like water.

- Dipole-dipole interactions – Moderate forces between polar molecules.

- London dispersion forces – Weak, temporary attractions in nonpolar molecules like oil.

When oil is introduced into water, there’s no dipole-dipole or hydrogen bonding possible between them. The only potential force—dispersion—is too weak to overcome water’s internal cohesion. So instead of mixing, the oil forms droplets that eventually coalesce into a separate layer, usually floating on top due to its lower density.

“Oil and water separation is a classic example of thermodynamic immiscibility driven by polarity mismatch.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Physical Chemist, University of Colorado

Real-World Example: Kitchen Chemistry

Imagine making a vinaigrette. You pour olive oil into a jar of vinegar (which is mostly water with acetic acid). At first, shaking creates tiny oil droplets suspended in the liquid—a temporary emulsion. But within seconds, the droplets begin merging. Within a minute, a clear layer of oil sits atop the vinegar.

This happens because agitation provides mechanical energy to disperse the oil, but once the energy stops, the system returns to its lowest-energy state: separated phases. To make the mixture last longer, cooks add an emulsifier—like mustard or egg yolk. These contain molecules with both polar and nonpolar regions (amphiphilic), which act as bridges between oil and water, stabilizing the emulsion.

How Emulsifiers Make Mixing Possible

While oil and water won’t mix on their own, humans have learned to cheat nature using emulsifiers. Mayonnaise, for example, combines oil and water (from lemon juice or vinegar) using egg yolk as an emulsifier. The key component in egg yolk is lecithin, a phospholipid with a hydrophilic (water-loving) head and a hydrophobic (water-fearing) tail.

Here’s how it works:

- Lecithin molecules surround oil droplets.

- Their hydrophobic tails embed into the oil.

- The hydrophilic heads face outward, interacting with water.

- This creates a protective barrier that prevents droplets from merging.

This principle is used widely in food science, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. Without emulsifiers, products like lotions, dressings, and sauces would quickly separate.

Common Emulsifiers in Daily Life

| Emulsifier | Found In | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Lecithin | Egg yolks, soybeans | Stabilizes mayonnaise, chocolate |

| Mustard | Condiments | Natural vinaigrette stabilizer |

| Polysorbate 80 | Ice cream, cosmetics | Prevents oil separation |

| Casein | Milk, cheese | Keeps fat dispersed in dairy |

Environmental and Industrial Implications

The immiscibility of oil and water isn’t just a kitchen curiosity—it has serious consequences in environmental science and engineering. Oil spills at sea demonstrate this dramatically. Crude oil, being less dense and nonpolar, spreads rapidly across the ocean surface, forming slicks that devastate marine ecosystems.

Cleanup efforts rely on this same principle of separation. Skimmers collect oil from the surface, while dispersants—chemical emulsifiers—are sometimes sprayed to break oil into tiny droplets, enhancing microbial degradation. However, these solutions are imperfect and can introduce new ecological risks.

In industrial processes, such as wastewater treatment, separating oil from water is critical. Gravity separators, coalescers, and centrifuges exploit density and polarity differences to purify water before discharge. Understanding the science behind immiscibility helps engineers design better systems for pollution control.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can oil and water ever truly mix?

No, not without assistance. On their own, oil and water remain immiscible due to polarity differences. However, with emulsifiers or high-shear mixing (like in homogenizers), stable emulsions can be created temporarily.

Why does oil float on water?

Most oils are less dense than water. For example, the density of water is about 1 g/mL, while vegetable oil is around 0.92 g/mL. Because of this difference, oil rises and forms a layer on top.

Are all oils nonpolar?

Virtually all common oils—vegetable, mineral, and essential oils—are predominantly nonpolar. However, some modified oils or those containing polar functional groups (like castor oil, which has hydroxyl groups) show limited polarity and can mix slightly better with water.

Practical Checklist: Working with Oil and Water

Whether you're cooking, cleaning, or conducting a science experiment, use this checklist to manage oil-water interactions effectively:

- ✅ Shake vigorously to create a temporary emulsion.

- ✅ Add an emulsifier (mustard, egg yolk, honey) when making dressings.

- ✅ Store oil-based products separately if long-term stability is needed.

- ✅ Use warm water to help loosen oily residues (heat increases kinetic energy).

- ✅ Avoid pouring oil down drains—use disposal containers to prevent clogs and pollution.

Conclusion: Respecting Nature’s Boundaries

The refusal of oil and water to mix is a perfect example of how molecular structure dictates macroscopic behavior. It’s not a flaw—it’s a feature of nature’s design. From the cells in our bodies (where lipid membranes separate aqueous environments) to the foods we eat and the environment we protect, this simple rule has profound implications.

Understanding the science empowers us to work with, not against, these natural tendencies. Whether you’re crafting the perfect sauce or responding to an ecological crisis, knowing why oil and water separate gives you the insight to find smarter solutions.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?