Molecular compounds form the foundation of much of the matter we interact with daily—from the water we drink to the oxygen we breathe. Unlike ionic compounds, which transfer electrons between atoms, molecular compounds rely on the sharing of electrons. This process, known as covalent bonding, is essential for understanding how nonmetal atoms achieve stability. But why do electrons get shared in the first place? The answer lies in atomic structure, energy minimization, and the universal drive toward chemical stability.

The Drive for Stability: The Octet Rule

Atoms are most stable when their outermost electron shell is full. For most elements, this means having eight valence electrons—a condition known as the octet rule. Noble gases like neon and argon naturally possess this configuration, making them chemically inert. Other elements, however, must gain, lose, or share electrons to reach this stable state.

Nonmetal atoms—such as hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and fluorine—tend to have high ionization energies, meaning they resist losing electrons. At the same time, their electron affinities make gaining electrons difficult unless paired with metals. Instead of transferring electrons, these atoms find a middle ground: sharing.

“Covalent bonding allows atoms to achieve noble gas configurations without forming ions, enabling the formation of stable, neutral molecules.” — Dr. Linda Park, Physical Chemist

How Electron Sharing Forms Covalent Bonds

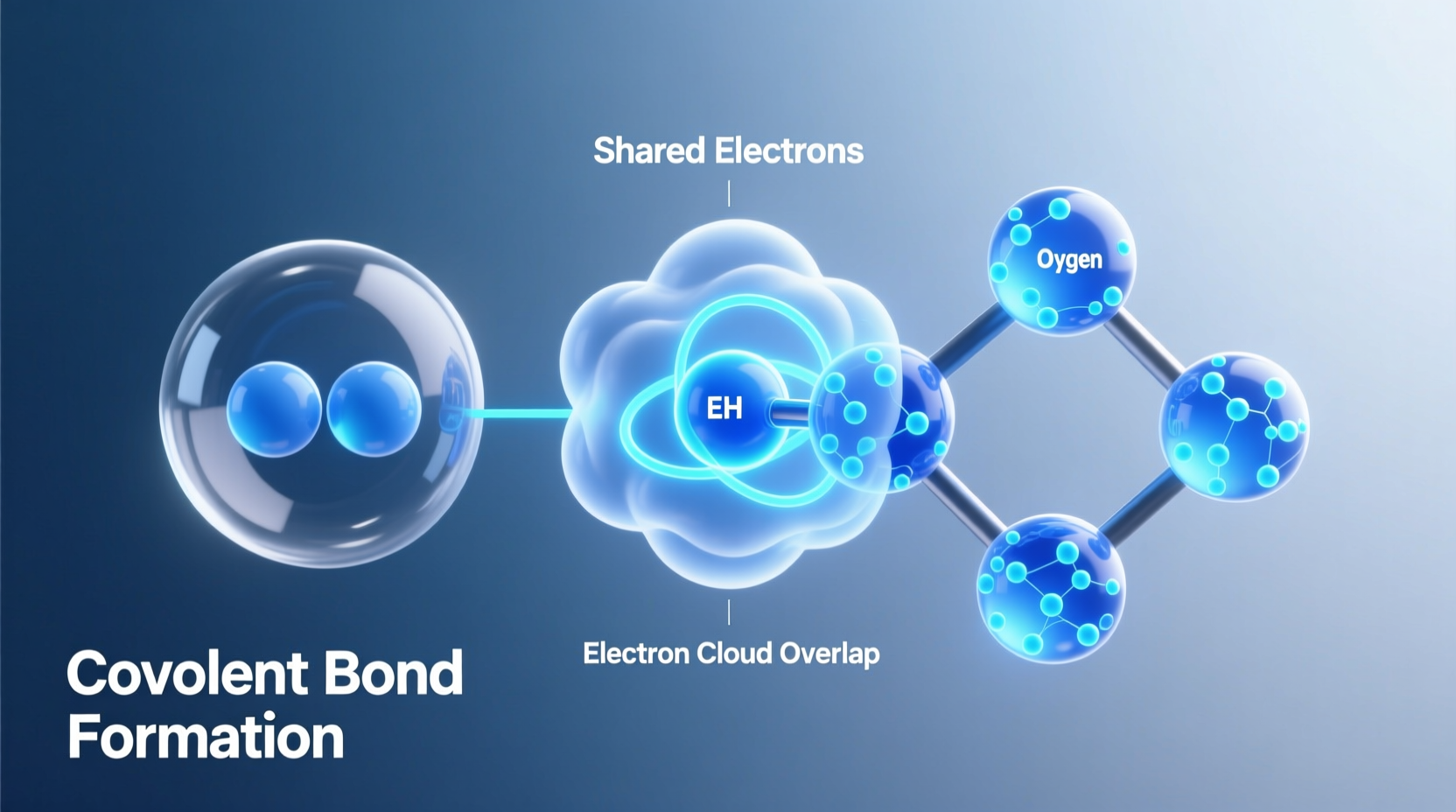

When two nonmetal atoms approach each other, their partially filled valence orbitals overlap. Each atom contributes one unpaired electron to form a shared pair. This shared pair effectively counts toward the octet (or duet, in hydrogen’s case) of both atoms involved.

For example, in a hydrogen molecule (H₂), each hydrogen atom has one electron. By sharing their electrons, both atoms achieve a stable duet configuration—similar to helium. Similarly, in a water molecule (H₂O), oxygen shares one electron with each of two hydrogen atoms, allowing oxygen to complete its octet and each hydrogen to complete its duet.

Types of Covalent Bonds: Single, Double, and Triple

Not all covalent bonds are equal. The number of shared electron pairs determines bond type and strength:

- Single bond: One shared pair (e.g., H–H in H₂)

- Double bond: Two shared pairs (e.g., O=O in O₂)

- Triple bond: Three shared pairs (e.g., N≡N in N₂)

As the number of shared pairs increases, so does bond strength and decreases bond length. Triple bonds are shorter and stronger than double or single bonds, making molecules like nitrogen gas exceptionally stable and less reactive under normal conditions.

Energy Efficiency in Bond Formation

Electron sharing isn’t just about fulfilling electron shells—it’s also about energy. When atoms form covalent bonds, the system releases energy, resulting in a more stable, lower-energy state. The energy released during bond formation is called bond energy. Breaking those bonds later requires an equivalent input of energy.

This principle explains why some molecules are highly stable (like methane, CH₄) while others are more reactive (like ozone, O₃). The balance between bond strength and molecular geometry dictates reactivity and physical properties.

Polarity and Unequal Sharing

While covalent bonds involve electron sharing, not all sharing is equal. Differences in electronegativity—the ability of an atom to attract shared electrons—can lead to polar covalent bonds.

In a water molecule, oxygen is more electronegative than hydrogen. As a result, the shared electrons spend more time near the oxygen atom, giving it a partial negative charge (δ⁻) and leaving the hydrogens with partial positive charges (δ⁺). This creates a polar molecule with distinct positive and negative ends, influencing properties like solubility and boiling point.

| Bond Type | Electronegativity Difference | Example | Electron Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonpolar Covalent | 0.0 – 0.4 | H₂, O₂ | Equal sharing |

| Polar Covalent | 0.5 – 1.6 | H₂O, HCl | Unequal sharing |

| Ionic | >1.7 | NaCl | Electron transfer |

This spectrum of bonding illustrates that electron sharing exists on a continuum. Pure covalent bonds occur between identical atoms, while increasing electronegativity differences shift the interaction toward ionic character.

Real-World Example: Carbon Dioxide Formation

Consider the formation of carbon dioxide (CO₂). Carbon has four valence electrons and needs four more to complete its octet. Oxygen has six and needs two. To satisfy both, one carbon atom forms double bonds with two oxygen atoms (O=C=O).

In this arrangement, each double bond consists of two shared electron pairs. Carbon shares four electrons (two with each oxygen), and each oxygen shares two with carbon. All atoms achieve stable electron configurations through mutual sharing—no electron transfer occurs.

This molecular compound is gaseous at room temperature, dissolves moderately in water, and plays a vital role in respiration and photosynthesis. Its properties stem directly from the nature of covalent bonding and linear molecular geometry.

Step-by-Step: How a Covalent Bond Forms

Understanding the sequence of events in covalent bond formation clarifies why sharing occurs:

- Approach: Two nonmetal atoms come close enough for their valence orbitals to overlap.

- Attraction: The nuclei of both atoms attract the valence electrons of the other.

- Sharing: Each atom contributes one electron to form a shared pair localized between the nuclei.

- Stabilization: The shared electrons lower the potential energy of the system, creating a stable bond.

- Equilibrium: The atoms settle at an optimal distance (bond length) where attractive and repulsive forces balance.

This process is governed by quantum mechanics, but the outcome is predictable: a stable molecule with lower energy than the separated atoms.

Checklist: Identifying Covalent Compounds

Use this checklist to determine if a compound involves electron sharing:

- ✅ Composed of two or more nonmetals

- ✅ No metal atoms present

- ✅ Low melting and boiling points

- ✅ Often exists as gases, liquids, or soft solids

- ✅ Poor electrical conductivity in all phases

- ✅ Formed via electron sharing, not transfer

- ✅ Represented by molecular formulas (e.g., CO₂, NH₃)

Frequently Asked Questions

Why don’t atoms just transfer electrons like in ionic compounds?

Nonmetals have high ionization energies, making it energetically unfavorable to lose electrons. They also lack the strong tendency to gain multiple electrons required for ionic bonding. Sharing offers a lower-energy path to stability.

Can more than two atoms share electrons?

Yes. In molecules like benzene (C₆H₆), electrons are delocalized across multiple atoms in resonance structures. This extended sharing increases stability and is common in organic chemistry.

Do all covalent bonds require two atoms?

While most covalent bonds are between two atoms, network covalent solids like diamond or silicon dioxide involve extensive three-dimensional networks where each atom is covalently bonded to several others.

Conclusion: The Power of Shared Electrons

Electron sharing is not a compromise—it’s a strategic solution evolved by nature to allow nonmetal atoms to achieve stability efficiently. Through covalent bonding, atoms form diverse and complex molecules essential to life and industry. From DNA to plastics, the world of molecular compounds thrives on the quiet cooperation of shared electrons.

Understanding why electrons are shared deepens appreciation for the invisible forces shaping our visible world. Whether you're studying chemistry, teaching it, or simply curious about how things work, recognizing the logic behind covalent bonds opens a window into the elegant design of matter.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?