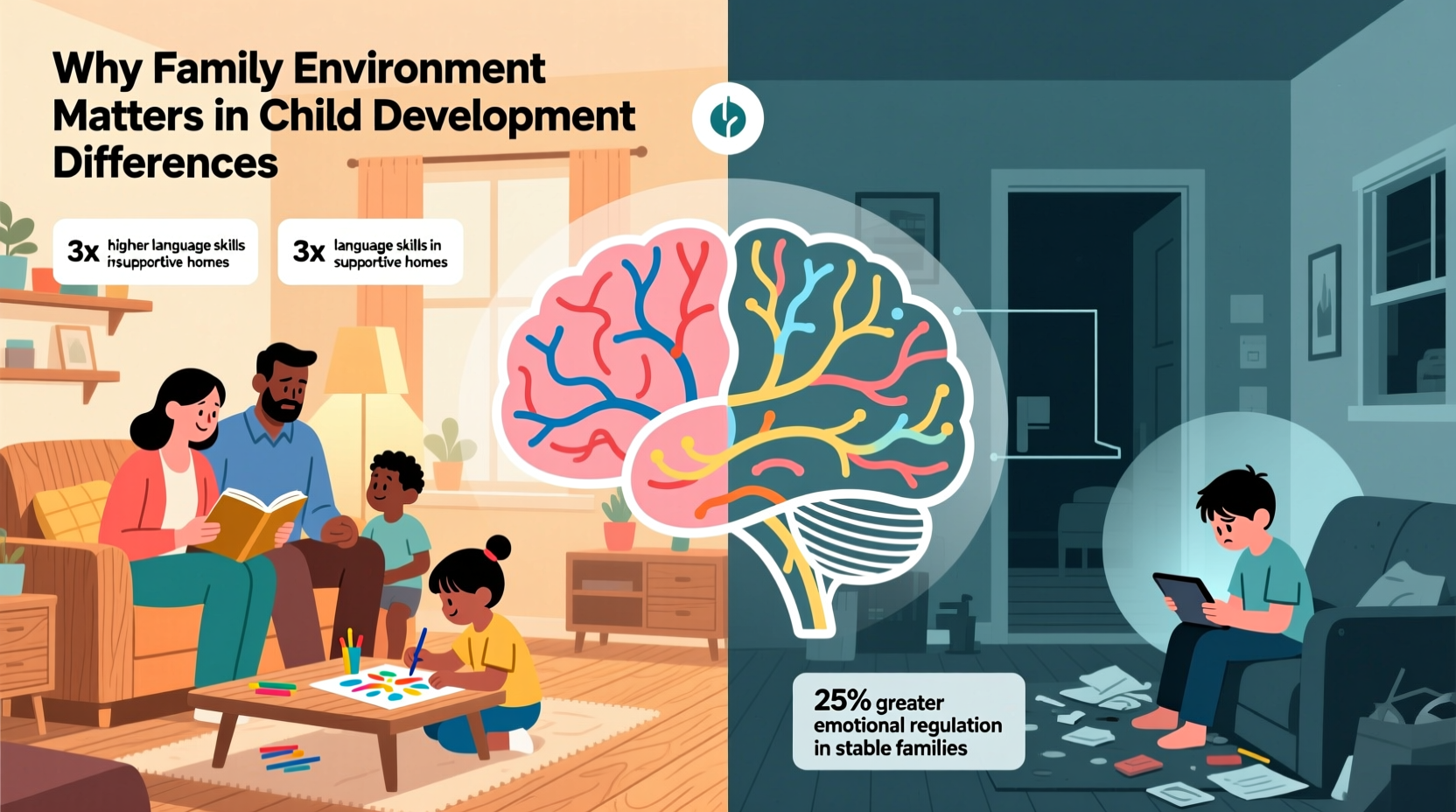

The earliest years of a child’s life are profoundly shaped by the world within their home. While genetics lay the biological foundation, it is the family environment that actively constructs the framework for emotional regulation, cognitive ability, social behavior, and long-term mental health. Research consistently shows that children raised in supportive, stable, and stimulating households tend to outperform peers from chaotic or neglectful backgrounds—not just academically, but across psychological and behavioral domains. The nuances of parenting styles, communication patterns, emotional availability, and socioeconomic conditions all converge within the family unit to create vastly different developmental trajectories.

The Role of Emotional Security in Early Development

Emotional security, primarily fostered through consistent caregiving and responsive interactions, is one of the most critical components of a healthy family environment. When children feel safe expressing emotions without fear of rejection or punishment, they develop stronger self-regulation skills and resilience. Secure attachment—formed when caregivers reliably meet a child’s physical and emotional needs—acts as a buffer against stress and supports brain development, particularly in regions responsible for emotion and decision-making.

In contrast, environments marked by emotional neglect, inconsistency, or hostility can lead to heightened cortisol levels, impairing neural connectivity and increasing vulnerability to anxiety, depression, and behavioral disorders. Children in such settings may struggle with trust, exhibit withdrawal or aggression, and face challenges forming healthy relationships later in life.

Parenting Styles and Their Long-Term Impact

Developmental psychologist Diana Baumrind identified four primary parenting styles, each linked to distinct outcomes in child development. These styles—authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and uninvolved—vary based on levels of responsiveness and demandingness.

| Parenting Style | Key Traits | Child Development Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Authoritative | High warmth, clear boundaries, open communication | Higher self-esteem, better academic performance, strong social skills |

| Authoritarian | Strict rules, low warmth, little flexibility | Compliance but lower creativity; higher risk of anxiety and rebellion |

| Permissive | High warmth, few rules, indulgent | Poor self-discipline, difficulty with authority, impulsivity |

| Uninvolved | Low warmth, minimal guidance, emotionally detached | Low motivation, poor emotional regulation, increased risk of delinquency |

Children raised under authoritative parenting—characterized by balance between structure and empathy—consistently demonstrate the most favorable developmental outcomes. This approach fosters autonomy while providing necessary guidance, teaching children that their voices matter within respectful limits.

“Children thrive not in perfection, but in predictability and love. A home where expectations are clear and affection is unconditional builds lifelong confidence.” — Dr. Elena Martinez, Child Psychologist

Socioeconomic Factors and Access to Resources

While emotional dynamics are central, material conditions significantly influence a family’s capacity to support optimal development. Families with greater financial stability often provide enriched learning environments: access to books, educational toys, extracurricular activities, quality childcare, and nutritious food. These resources directly contribute to cognitive stimulation and school readiness.

Conversely, economic hardship can introduce chronic stress into the home. Parents working multiple jobs may have limited time for engagement, and unstable housing or food insecurity can disrupt routines essential for child well-being. It's crucial to note that poverty does not equate to poor parenting—many low-income families foster exceptional emotional support—but systemic constraints can limit opportunities regardless of parental effort.

Language exposure is one stark example. Studies show that by age three, children from professional families hear roughly 30 million more words than those from welfare-supported homes—a gap strongly correlated with vocabulary size, literacy rates, and academic achievement.

A Real Example: Two Siblings, Different Environments

Consider Maria and her younger brother, Javier. Both born to the same parents, they experienced markedly different early environments due to shifting family circumstances. When Maria was young, her mother worked night shifts and was often emotionally drained. Communication was minimal, routines inconsistent. By contrast, when Javier was born, the family had moved to a safer neighborhood, and her mother had transitioned to daytime work with flexible hours. She engaged more actively—reading nightly, establishing rituals, attending parent groups.

By kindergarten, Javier displayed stronger language skills, greater emotional awareness, and smoother peer interactions. Maria, though intelligent and creative, struggled with attention and exhibited anxiety around authority figures. Their genetic makeup was similar, but environmental timing and stability created divergent developmental paths.

Communication Patterns That Shape Identity

How families talk—or don’t talk—shapes a child’s sense of self. Open dialogue where opinions are valued nurtures critical thinking and self-worth. In homes where criticism dominates or emotional topics are avoided, children learn to suppress feelings and doubt their perceptions.

Active listening, using “I” statements, and resolving conflicts constructively model healthy interpersonal skills. For instance, saying “I felt worried when you didn’t call after school” instead of “You never think about anyone but yourself!” teaches accountability without blame. These subtle linguistic habits accumulate over time, influencing how children interpret relationships and manage conflict.

- Encourage children to express opinions during family discussions.

- Avoid dismissive phrases like “You’re too sensitive” or “Stop crying.”

- Validate emotions before offering solutions (“I see you’re upset. Want to tell me what happened?”).

Step-by-Step Guide to Strengthening Family Environment

- Establish Daily Routines: Predictable schedules for meals, bedtime, and homework reduce anxiety and build structure.

- Practice Active Listening: Put down devices, make eye contact, and reflect back what your child says.

- Create a Calm-Down Space: Designate a quiet corner with comforting items for emotional regulation.

- Hold Weekly Family Meetings: Discuss upcoming events, resolve minor conflicts, and celebrate wins together.

- Model Emotional Intelligence: Narrate your own feelings (“I’m feeling frustrated, so I’ll take deep breaths”).

Checklist: Building a Supportive Family Climate

- ✅ Prioritize quality time (even 15 minutes of focused attention daily)

- ✅ Set consistent, fair boundaries with natural consequences

- ✅ Encourage curiosity and independent problem-solving

- ✅ Limit screen time during meals and before bed

- ✅ Express affection verbally and physically (hugs, praise)

- ✅ Address conflicts calmly, avoiding yelling or sarcasm

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a positive school environment overcome a negative family background?

To some extent, yes. Supportive teachers, mentors, and structured programs can mitigate adverse home experiences. However, sustained improvement usually requires coordinated efforts between school and family. A child spends far more waking hours at home, making family dynamics foundational even when external support is strong.

Is it too late to improve family environment if my child is already older?

No. While early childhood is a critical window, the brain remains malleable throughout adolescence. Changes in communication, emotional availability, and consistency can still significantly impact a teenager’s self-concept and behavior. It’s never too late to rebuild trust and strengthen bonds.

What if one parent uses harsh discipline while the other is nurturing?

Inconsistency confuses children and undermines security. Unified parenting approaches are ideal. Couples should discuss values privately and present a united front. If conflict persists, family counseling can help align strategies and reduce mixed messages.

Conclusion: Shaping Futures One Home at a Time

The family environment is not merely a backdrop to child development—it is an active architect of who a child becomes. From the tone of voice used during disagreements to the presence of bedtime stories, every interaction contributes to neural pathways, emotional intelligence, and worldview. Differences in these everyday experiences explain why two children with similar potential can grow into vastly different adults.

Improving family dynamics doesn’t require perfection. It demands awareness, intention, and small, consistent actions. Whether you're reinforcing routines, choosing empathy over control, or simply being present, each step fosters a healthier developmental ecosystem. The ripple effects extend beyond individual homes—they shape classrooms, workplaces, and communities.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?