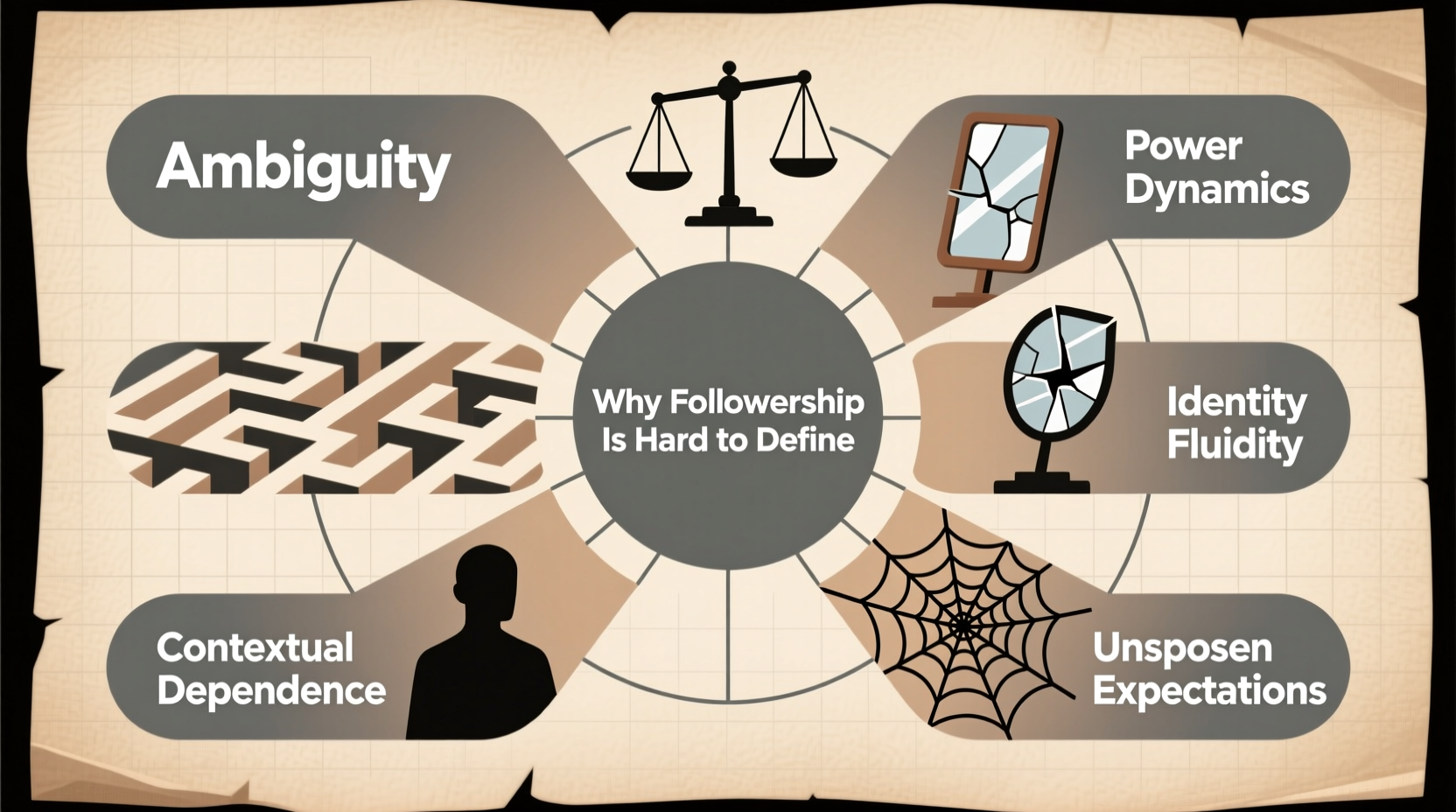

Few concepts in organizational behavior are as quietly influential yet intellectually elusive as followership. While leadership has been dissected across decades of research, books, and training programs, followership remains in the shadows—often assumed, rarely examined. When scholars and practitioners attempt to define what it means to be a follower, they quickly encounter contradictions, context dependence, and shifting expectations. The difficulty in pinning down a universal definition isn't accidental; it reflects deeper structural, cultural, and psychological complexities inherent in how people engage with authority, contribute to teams, and navigate power.

This ambiguity matters. Without a clear understanding of followership, organizations risk undervaluing critical contributors, misdiagnosing team dysfunction, and designing leadership development programs that ignore half the equation. To truly grasp why followership resists easy definition, we must explore the core challenges that make it such a slippery concept.

The Fluid Nature of Follower Roles

One of the primary reasons followership defies definition is its dynamic and context-sensitive nature. Unlike formal job descriptions or hierarchical titles, being a follower isn’t a fixed role. It shifts moment by moment based on expertise, situation, and objectives. In one meeting, an employee may follow a manager’s lead; in the next, they may become the de facto leader due to their technical knowledge.

This fluidity undermines attempts to create static models of followership. Consider a software development team: during sprint planning, developers follow the product owner’s vision. But when debugging a critical issue, the most junior developer with niche experience might suddenly guide senior colleagues. Followership here isn’t about rank—it’s about relevance.

Lack of Universal Standards Across Cultures

Cultural norms profoundly shape how followership is perceived and enacted. In hierarchical cultures—such as those common in parts of Asia, the Middle East, or traditional corporate structures—followers are expected to show deference, avoid public disagreement, and execute directives without question. Initiative may be seen as overstepping.

In contrast, Western, particularly Scandinavian and North American, organizational cultures often encourage followers to challenge ideas, offer feedback, and co-create solutions. Here, “good” followership includes speaking up, even if it means contradicting a superior.

This divergence makes it impossible to establish a single, globally applicable definition. What constitutes respectful engagement in Tokyo might be interpreted as disengagement in Stockholm or insubordination in Seoul.

“Followership cannot be understood outside the cultural grammar of authority and participation.” — Dr. Lena Moretti, Organizational Psychologist, ETH Zurich

The Misconception That Followers Are Passive

A persistent myth equates followership with passivity. This stereotype paints followers as compliant, unthinking recipients of orders—mere cogs in a leadership-driven machine. This view not only distorts reality but also devalues the cognitive and emotional labor involved in effective following.

Research by Kelley (1992) challenged this assumption by introducing the concept of the “effective follower,” someone who is both independent and committed, capable of critical thinking while remaining aligned with group goals. Yet, popular discourse—and many organizational reward systems—still favor visible leadership behaviors over quieter forms of contribution.

The consequence? Employees suppress dissent, withhold ideas, or disengage because they believe initiative belongs only to those with titles. Organizations lose out on innovation and early warning signals simply because they fail to recognize active followership when they see it.

Power Asymmetry and Fear of Consequence

Even in environments that claim to value open communication, real or perceived power imbalances make authentic followership risky. Employees may possess crucial insights but remain silent due to fear of retaliation, marginalization, or career stagnation. This gap between willingness and ability to engage defines one of the central paradoxes of modern followership.

In hierarchical organizations, subordinates often interpret “being a good follower” as agreeing with superiors, regardless of personal judgment. Psychological safety—the belief that one won’t be punished for speaking up—is a prerequisite for meaningful followership, yet it remains absent in many workplaces.

Without safety, followership becomes performative rather than substantive. People follow scripts, not principles.

Multiple Dimensions of Followership Behavior

Scholars have proposed various typologies to categorize followers, but none have achieved consensus. One widely cited model by Robert Kelley identifies five follower types:

| Follower Type | Key Traits | Organizational Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Exemplary | Independent, critical thinker, highly engaged | Drives innovation and accountability |

| Conformist | Reliable but passive, follows rules without questioning | Maintains stability, may resist change |

| Passive | Low engagement, minimal initiative | Risks groupthink and inertia |

| Alienated | Critical but disengaged, cynical | Can identify flaws but doesn’t help solve them |

| Pragmatic Survivor | Adaptable, plays politics, self-protective | Navigates complexity but may lack integrity |

The existence of multiple models highlights the difficulty of reducing followership to a single behavioral profile. Is a follower defined by loyalty? Initiative? Alignment? Critical thinking? The answer depends on organizational priorities and situational demands.

Mini Case Study: The Silent Analyst

In a mid-sized financial firm, a junior data analyst noticed inconsistencies in a quarterly report flagged for executive presentation. Though confident in her findings, she hesitated to speak up during the review meeting. Her manager had a reputation for dismissing input from junior staff, and past attempts at feedback had been met with subtle reprimands.

She chose to share her concerns privately with a peer, who later mentioned them in passing to a director. The error was corrected hours before the board meeting. While the mistake was avoided, the system failed: the most qualified person to raise the issue felt unable to do so in the moment. Her followership was technically accurate—she didn’t disrupt the meeting—but substantively inadequate because the organization’s culture suppressed constructive challenge.

This case illustrates how structural and interpersonal dynamics can distort followership, making it less about competence and more about survival.

Tips for Rethinking Followership in Practice

- Evaluate followership not by obedience, but by contribution quality and alignment with shared goals.

- Create rituals for dissent, such as “red team” reviews or anonymous feedback channels.

- Recognize and reward employees who ask tough questions or surface risks.

- Train managers to distinguish between respectful challenge and insubordination.

- Encourage role rotation where team members take turns leading and following projects.

Checklist: Building a Healthier Followership Culture

- Assess psychological safety using anonymous surveys.

- Clarify expectations: what does “active followership” look like in your team?

- Model vulnerability by leaders admitting mistakes or asking for help.

- Include followership competencies in performance evaluations.

- Rotate meeting facilitation roles to distribute leadership opportunities.

FAQ

Is followership just the opposite of leadership?

No. Followership is not the inverse of leadership but a complementary dynamic. Effective followers often display leadership qualities like initiative and accountability, just within a different scope of influence.

Can someone be a good follower without being a good leader?

Yes. Excellence in followership requires distinct skills—listening, alignment, constructive feedback, execution discipline—that don’t always overlap with leadership traits like vision-setting or delegation.

Why don’t organizations train people in followership?

Most organizations prioritize leadership development due to historical bias and visibility. However, this oversight limits team effectiveness. Training in active followership can improve decision-making, reduce errors, and enhance collaboration.

Conclusion

Followership resists definition not because it lacks substance, but because it is too rich, too contextual, and too human to be reduced to a simple formula. Its complexity arises from cultural variation, shifting roles, power dynamics, and the quiet courage required to contribute meaningfully without authority. Recognizing these challenges is the first step toward building organizations where contribution is valued regardless of title.

To move forward, leaders must stop seeing followership as the default state of those not in charge and start treating it as a skilled practice worthy of attention, cultivation, and respect. Only then can teams achieve true interdependence—where leading and following flow naturally, based on need, not hierarchy.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?