The common housefly buzzes around homes, parks, and picnic tables with an annoying persistence that few insects match. But have you ever paused mid-swat to wonder: why is it called a *fly* in the first place? The answer might seem obvious—flies fly—but language is rarely that straightforward. Behind this simple word lies a rich tapestry of etymology, evolution, and historical coincidence that stretches back thousands of years.

Understanding why we call this insect a \"fly\" isn't just about entomology; it's a journey into how languages shape our perception of the natural world. From Proto-Indo-European roots to Old English poetry, the story of the word “fly” reveals how human observation, grammar, and even metaphor influence naming conventions across time.

The Linguistic Roots of “Fly”

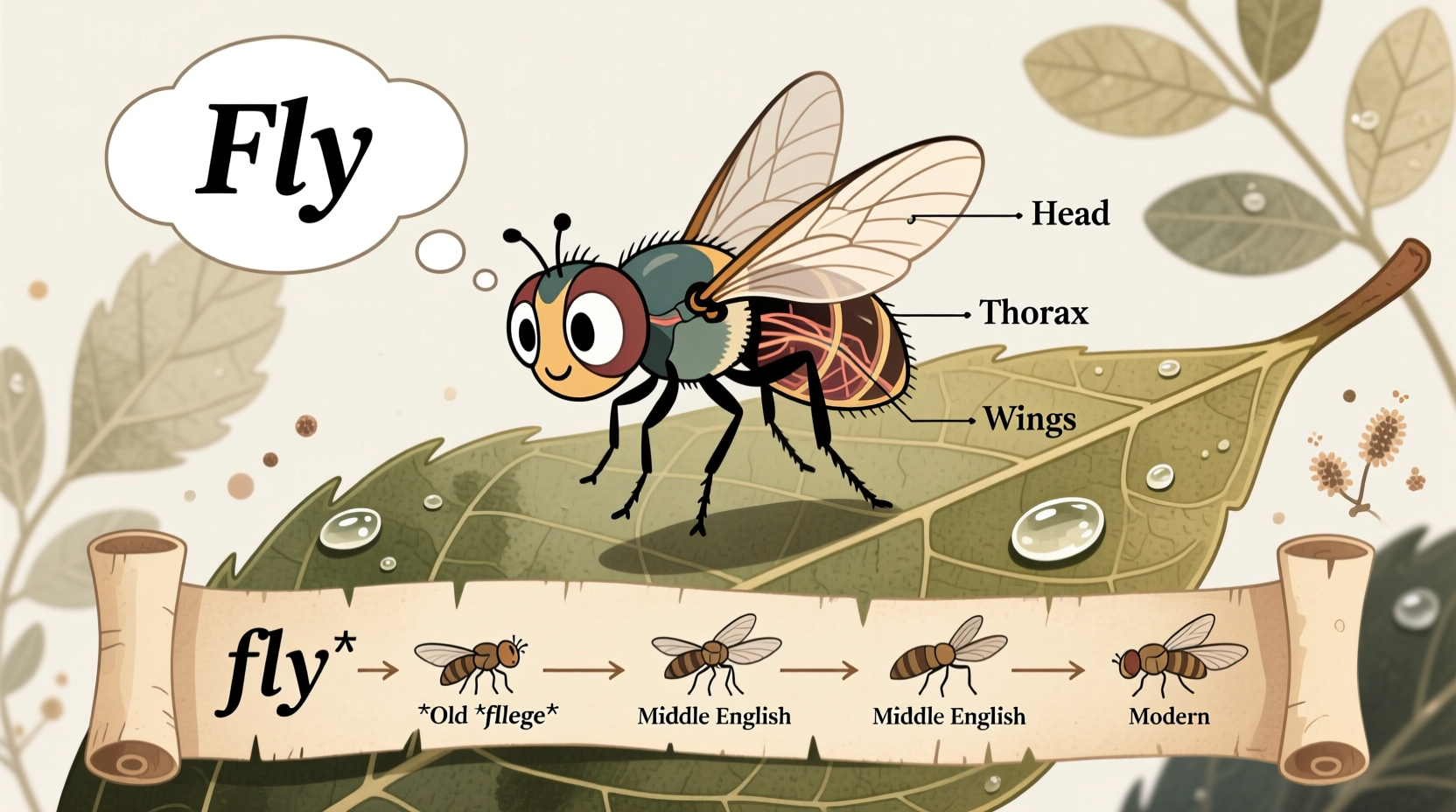

The word “fly” as a noun referring to the winged insect comes from the Old English *flēoge*, which itself derives from the Proto-Germanic *fleugōn*. This ancient root is tied to the verb “to fly,” originating from *fleuganą*, meaning “to soar” or “to move through air.” In fact, the noun and verb were once more closely linked in form and function.

Interestingly, in early Germanic languages, the same root was used both for the creature and the action. Over time, the noun diverged slightly in pronunciation but retained its phonetic core. Compare Old English *flēogan* (to fly) with *flēoge* (a fly)—the connection is unmistakable.

This pattern isn’t unique. Many animals are named after their most distinctive behavior: spiders “spin,” larks “lark,” and fleas “flee.” The fly earns its name not by appearance, but by motion—the defining trait that sets it apart from crawling insects like ants or beetles.

“Language often prioritizes movement over morphology when naming creatures. A fly is named for what it does, not what it looks like.” — Dr. Lydia Chen, Historical Linguist, University of Cambridge

From Verb to Noun: Grammatical Evolution

In Old English, many animal names emerged as deverbal nouns—words derived from verbs. This process helped speakers quickly categorize animals based on observable behaviors. For example:

- Bear – from “to bear” (cub-bearing)

- Hound – related to “to hunt”

- Fly – from “to fly”

The transformation from verb to noun followed a common grammatical rule: add a suffix like *-a*, *-e*, or *-u* to denote the agent performing the action. So, something that *flies* becomes a *fly*. It’s a concise, functional naming system rooted in utility rather than taxonomy.

A Name Shared Across Species

While “fly” today commonly refers to the housefly (*Musca domestica*), the term technically applies to any member of the order Diptera—“two-winged” insects. This includes mosquitoes, gnats, midges, and crane flies. All share the ability to fly, though some do so more gracefully than others.

The scientific classification reinforces the behavioral logic behind the name. Diptera comes from Greek: *di-* (two) and *pteron* (wing). Even in Latin-based taxonomy, flight remains central to identity.

Yet colloquially, not all flying insects are called flies. Bees, wasps, and butterflies aren’t referred to as “flies,” despite being more agile fliers than many true flies. This inconsistency highlights how cultural context shapes language. “Fly” became reserved for small, fast-moving, often pest-like insects associated with decay or annoyance.

Common Misconceptions About the Name

Some assume “fly” was chosen because these insects are difficult to catch—“they’re so quick, they just fly away!” While poetic, this folk etymology lacks historical support. The name predates such figurative interpretations and is firmly grounded in literal locomotion.

Another myth suggests the word originated from the idea that flies “fly around garbage,” linking “fly” to filth. However, the term existed long before sanitation science, and many non-pest species also carry the name (e.g., fruit flies, hoverflies).

Parallels in Other Languages

The link between motion and naming appears globally. Consider these examples:

| Language | Word for “Fly” | Literal Meaning / Root |

|---|---|---|

| German | Fliege | From *fliegen* – “to fly” |

| Dutch | Vlieg | Related to “vliegen” – “to fly” |

| Swedish | Fluga | From *flyga* – “to fly” |

| Russian | муха (mukha) | No direct link to flight; possibly imitative of buzzing |

| Japanese | ハエ (hae) | Possibly derived from archaic words for “hovering” |

Notice that Germanic languages mirror English in deriving the noun from the verb of flight. Slavic and East Asian languages often use onomatopoeia or descriptive terms instead, showing different cognitive approaches to categorization.

Historical Usage and Cultural Impact

Early English texts frequently mention flies, not just as pests but as metaphors. In Shakespeare’s *King Lear*, the character Edgar says: “…as flies to wanton boys, are we to th’ gods—they kill us for their sport.” Here, the fly symbolizes fragility and insignificance, yet its name remains rooted in mobility.

Medieval bestiaries rarely classified insects systematically, but they noted the fly’s constant motion. One 12th-century manuscript describes the *flēoge* as “ever in flight, never at rest,” reinforcing the behavioral basis of its name.

Even in religious symbolism, the fly’s name influenced its role. In some traditions, Beelzebub—the “Lord of the Flies”—derives from a mocking title given to a Philistine god, where “Ba’al Zebub” may have been misheard or reinterpreted as “Lord of the Flies” due to the association of flies with decay and corruption. Again, the name’s connotation evolved beyond mere locomotion.

Mini Case Study: The Naming of the Fruit Fly

In biological research, *Drosophila melanogaster*—commonly known as the fruit fly—is a cornerstone of genetic studies. Despite having “fly” in its common name, it shares the same etymological origin: it flies. But unlike the housefly, it’s drawn to fermenting fruit, not waste.

When scientists in the early 20th century began using *Drosophila* in labs, they adopted the familiar term “fruit fly” for clarity. The name stuck, demonstrating how practicality and existing linguistic patterns guide scientific vernacular—even when precision might suggest otherwise.

This case shows that while taxonomy uses Latin, public understanding relies on accessible, behavior-based names. Calling it a “small dipteran insect attracted to fruit” would be accurate but impractical. “Fruit fly” works because it aligns with how people already think and speak.

FAQ

Why isn’t a butterfly called a fly if it flies?

Although butterflies fly, their name emphasizes transformation (“butter” may be a corruption of “flutter,” or unrelated to dairy). Unlike “fly,” which centers on motion alone, “butterfly” reflects appearance and folklore. Additionally, butterflies belong to a different insect order (Lepidoptera), and their graceful flight contrasts with the erratic movement of true flies.

Are all insects called ‘flies’ actually flies?

No. Mayflies, dragonflies, and fireflies are not true flies (Diptera). They have four wings and different anatomies. These names use “fly” poetically, describing appearance or behavior, not biological classification. True flies have only two wings and belong to the order Diptera.

Did the verb “to fly” come before the insect name?

Linguistically, the verb likely predates the noun. Early humans would have observed birds and wind before naming specific insects. The concept of flight existed first; the insect was later named after the action it performs.

Conclusion: Why Names Matter

The word “fly” seems trivial until you trace its path through centuries of speech and thought. It’s a testament to how humans simplify complexity by focusing on key traits—flight, in this case. We don’t name creatures solely by DNA or anatomy, but by what we see them *do*.

Next time you swat at a fly, remember: its name isn’t arbitrary. It’s a linguistic fossil, preserving ancient ways of seeing the world. Language evolves, but some words remain anchored in motion, memory, and meaning.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?