The ladybird, with its bright red shell and distinctive black spots, is one of the most recognizable insects in gardens across Europe, North America, and beyond. But despite its cheerful appearance, few pause to consider why it's called a \"ladybird\"—a name that seems oddly formal for such a tiny creature. The answer lies not in modern naming conventions but in centuries-old religious beliefs, linguistic evolution, and cultural reverence for nature’s helpers.

This seemingly whimsical name has deep roots in medieval Europe, where language, faith, and agriculture intertwined to shape how people perceived even the smallest creatures. Understanding the origin of “ladybird” reveals more than just word history—it offers insight into how humans have historically viewed the natural world as both practical and sacred.

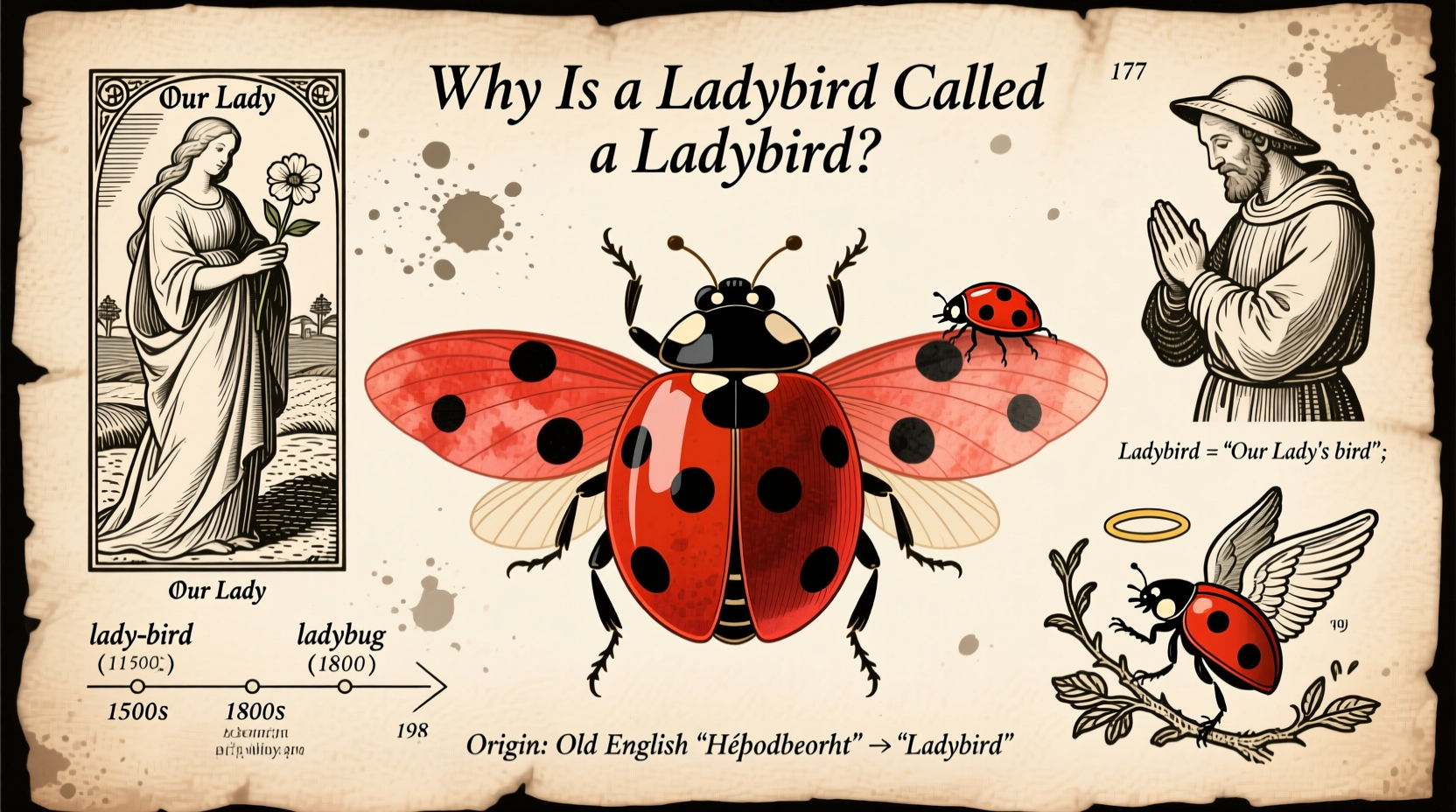

The Religious Roots: “Our Lady’s Bird”

The term “ladybird” traces back to the Middle Ages in England and continental Europe. During this period, many common names for animals and plants were influenced by Christian symbolism. The ladybird was no exception.

Farmers noticed that these small beetles appeared during spring and summer, often coinciding with the decline of aphid populations—pests that devastated crops. Because the insects arrived at a time when fields needed protection and seemed to bring relief, they were seen as beneficial—and perhaps even divinely sent.

The “lady” in “ladybird” refers to the Virgin Mary, known in medieval Catholic tradition as “Our Lady.” Thus, the insect was originally called “Our Lady’s bird.” This name reflected gratitude: farmers believed that Mary had sent the beetle to protect their crops from destruction.

“Names like ‘Our Lady’s beetle’ reveal how deeply religion shaped rural life. These insects weren’t just useful—they were seen as messengers of divine care.” — Dr. Eleanor Hartman, Medieval Cultural Historian

Over time, “Our Lady’s bird” was shortened to “lady’s bird,” and eventually “ladybird.” In other European languages, similar references exist: the German *Marienkäfer* means “Mary’s beetle,” while the Dutch *lieveheersbeestje* translates to “dear little animal of our Lord.” Even French uses *bête à bon Dieu*, meaning “creature of God.” All point to a shared cultural narrative of spiritual blessing tied to agricultural prosperity.

Linguistic Evolution Across Regions

While “ladybird” dominates British English, American English typically uses “ladybug”—a variation that emerged in the 19th century. The shift from “bird” to “bug” reflects changing scientific literacy and colloquial preferences. “Bug” became a general term for small insects, even though ladybirds are technically beetles (family Coccinellidae), not true bugs (which belong to the order Hemiptera).

The original use of “bird” in “ladybird” may seem odd today, but in older English dialects, “bird” was sometimes used generically for small creatures, especially those that moved quickly or flew. It wasn’t meant literally. For example, the phrase “the young birds” could refer to children, and “bird” alone might describe any nimble animal. So “ladybird” likely followed this pattern—a poetic term for a small, fluttering creature associated with a holy figure.

Why the Seven Spots Matter: Symbolism and Superstition

Many species of ladybirds, particularly the seven-spot ladybird (*Coccinella septempunctata*), feature exactly seven black spots on a red background. This number held symbolic importance in medieval Christian thought—the seven joys, seven sorrows, or seven virtues. Some folk tales suggest the seven spots represent the seven sorrows of the Virgin Mary, reinforcing the religious connection.

Across cultures, the ladybird has been seen as a bearer of good luck. In parts of rural England, children were taught not to harm them, believing that killing a ladybird would bring rain or misfortune. Others believed that if a ladybird landed on you, it would grant a wish or signal an upcoming change in life.

In agricultural communities, the arrival of ladybirds was celebrated as a sign of healthy soil and balanced ecosystems. Their presence indicated that natural pest control was underway—long before modern science confirmed their role in biological control.

Scientific Classification vs. Common Names

Despite being called a “bird” or a “bug,” the ladybird is neither. It belongs to the order Coleoptera—beetles—and is part of the family Coccinellidae, which includes over 6,000 species worldwide. True bugs belong to a different order (Hemiptera) and have piercing-sucking mouthparts; ladybirds have chewing mouthparts and hardened forewings (elytra), classic traits of beetles.

The confusion between common names and scientific classification persists today. While “ladybug” is widely used in North America, entomologists prefer “ladybird beetle” to reflect accuracy. However, the informal name endures due to its cultural familiarity and child-friendly appeal.

| Term | Region | Accuracy | Cultural Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ladybird | UK, Ireland, Australia | Moderate (not a bird) | Medieval Christian tradition |

| Ladybug | United States, Canada | Low (not a true bug) | Colloquial simplification |

| Ladybird Beetle | Scientific, global | High | Entomological precision |

| Marienkäfer | Germany | N/A | “Mary’s beetle” – religious |

| Bête à bon Dieu | France | N/A | “Creature of God” – folk belief |

Modern Significance and Conservation

Today, the ladybird remains a symbol of ecological balance. Gardeners and farmers still welcome them as natural predators of aphids, mites, and scale insects. A single ladybird can consume up to 5,000 aphids in its lifetime, making it a powerful ally in sustainable agriculture.

However, some non-native species, like the harlequin ladybird (*Harmonia axyridis*), introduced for pest control, have become invasive. They outcompete native species and can invade homes in large numbers during winter. This duality—helper and potential pest—adds complexity to their legacy.

Conservation efforts now focus on protecting native ladybird populations through habitat preservation and reduced pesticide use. Citizen science projects, such as the UK’s “Ladybird Survey,” encourage the public to report sightings and help track population trends.

Mini Case Study: The Garden That Healed Itself

In Devon, UK, a community garden struggled with aphid infestations on kale and beans. After repeated organic sprays failed, volunteers planted yarrow, dill, and tansy around crop borders—plants known to attract ladybirds. Within weeks, native seven-spot ladybirds appeared. Over the next growing season, aphid levels dropped by 80%, and chemical interventions ceased. The gardeners credited the turnaround not to human effort alone, but to the return of nature’s own pest controllers.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is a ladybird really a bird?

No, a ladybird is not a bird. The name comes from the medieval term “Our Lady’s bird,” referring to the Virgin Mary. It has nothing to do with avian species.

Are all ladybirds red with black spots?

No. While the classic image is red with black spots, ladybirds come in many colors and patterns—yellow, orange, pink, or even black—with varying numbers of spots or none at all. Species differ widely in appearance.

Why do some people call it a ladybug instead of a ladybird?

“Ladybug” is primarily used in North America and reflects a shift toward simpler, more literal language. “Bug” became a catch-all term for insects, even though ladybirds are technically beetles.

Expert Insight: Bridging Language and Ecology

“The name ‘ladybird’ is a beautiful example of how culture shapes our relationship with nature. It reminds us that conservation isn’t just about data—it’s also about stories, names, and the meanings we attach to living things.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Environmental Linguist, University of Edinburgh

Actionable Checklist: Supporting Ladybirds in Your Environment

- Plant nectar-rich flowers like marigolds, cosmos, and fennel to attract adult ladybirds.

- Avoid using chemical pesticides that harm beneficial insects.

- Leave some leaf litter or install insect hotels to provide overwintering habitats.

- Learn to identify native vs. invasive ladybird species in your area.

- Participate in local biodiversity surveys or citizen science programs.

Conclusion: A Name Steeped in History and Hope

The name “ladybird” carries centuries of meaning—from medieval prayers whispered over crops to modern gardeners rejoicing at the sight of a spotted beetle. It is a testament to how language preserves cultural memory, blending reverence, utility, and folklore into a single word.

Understanding the etymology of “ladybird” does more than satisfy curiosity; it deepens our appreciation for the interconnectedness of language, belief, and ecology. As we face growing environmental challenges, remembering the stories behind names can inspire greater respect for even the smallest members of our ecosystem.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?