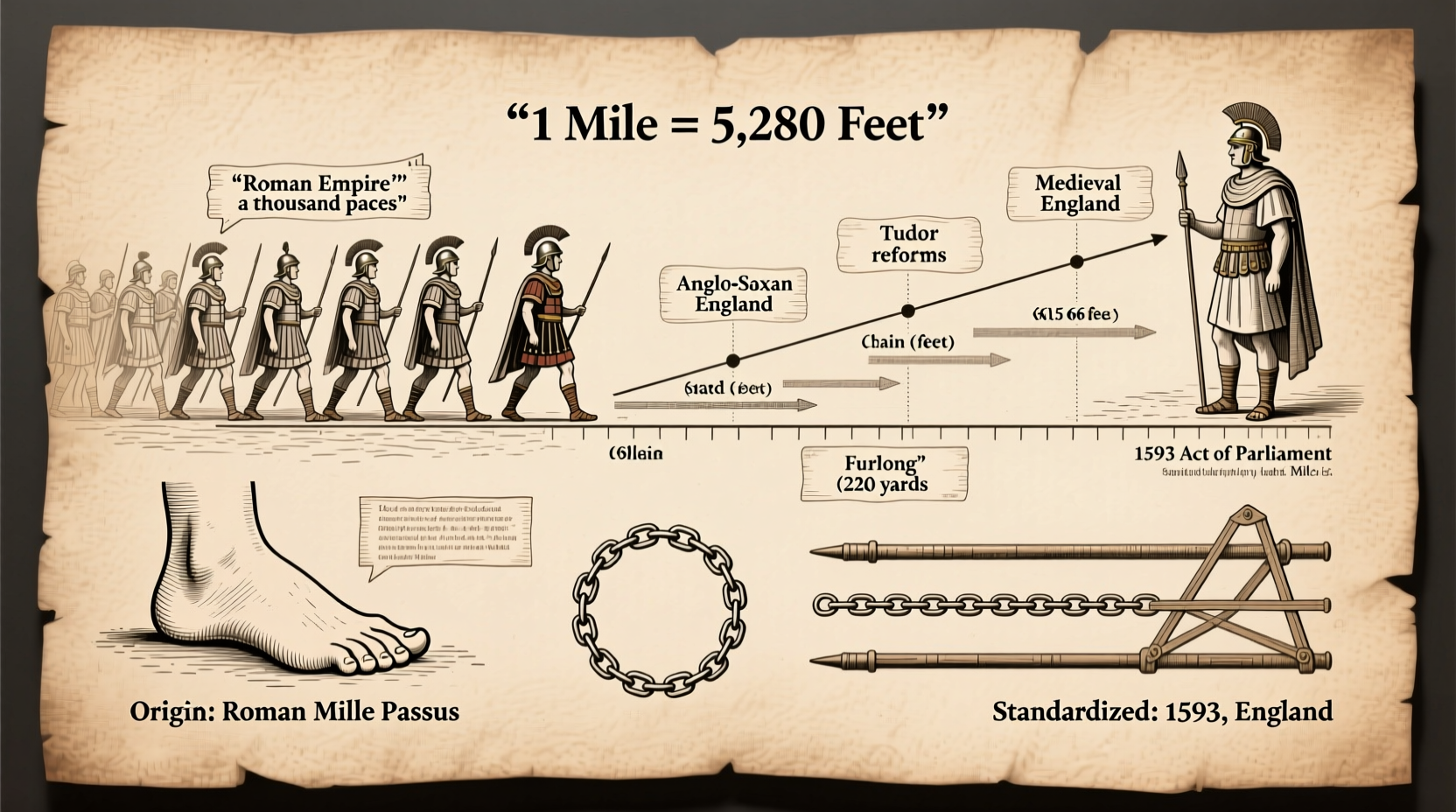

The mile is a unit of measurement so deeply embedded in daily life—used for road signs, track events, and fitness tracking—that few stop to ask why it’s exactly 5,280 feet long. It doesn’t divide neatly into round numbers, nor does it align with the metric system’s base-10 logic. So how did this seemingly arbitrary number become the standard? The answer lies in centuries of evolving measurement systems, political decisions, and practical compromises that ultimately shaped the mile as we know it today.

Roman Roots: The Mile Begins with \"Mille Passus\"

The concept of the mile originated in ancient Rome, where distance was measured by pace. The Latin term *mille passus* translates to “a thousand paces.” Each pace was considered two steps—one for each foot—making a single pace about 5 Roman feet. Therefore, a Roman mile equaled 1,000 paces or 5,000 Roman feet.

This system was highly effective for military use. Roman legions relied on consistent measurements to plan marches, construct roads, and maintain supply lines across the vast empire. Milestones were placed along major routes, marking each *mille passus*. These markers helped standardize travel and administration throughout Europe.

However, the Roman foot was shorter than the modern foot—approximately 11.6 inches compared to today’s 12 inches. This means a Roman mile was roughly 4,850 modern feet, significantly shorter than the current 5,280.

The Evolution of English Measurement Systems

After the fall of the Roman Empire, standardized measurement declined across Europe. In England, local customs governed units of length, leading to regional inconsistencies. By the Middle Ages, various definitions of the mile existed, often based on agricultural or geographical references rather than military pacing.

One such variation was the “London mile,” used in trade and city planning, which measured around 5,000 feet. Another was the “geographical mile,” tied to latitude calculations, while the “Irish mile” reached 6,720 feet. This lack of uniformity created confusion, especially as trade and transportation expanded.

To bring order, English authorities began attempting standardization. In the 13th century, King Edward I introduced reforms emphasizing consistency in weights and measures. His efforts laid groundwork for future unification, though no definitive mile was established during his reign.

The Statute Mile: A Royal Decision in 1593

The moment the mile became exactly 5,280 feet occurred under Queen Elizabeth I in 1593, through an act of Parliament known as the *Statute of 35 Elizabeth I, Cap. 6*. Officially titled “An Act against the Multiplying of Buildings within the Verge of the Court of Westminster,” this law aimed to control urban sprawl—but included a crucial definition of distance.

The statute defined the mile in relation to another traditional unit: the furlong. One furlong equaled 660 feet, a length derived from the typical size of a plowed field in medieval agriculture (one furrow long). There were eight furlongs in a mile. Simple math reveals the result: 8 × 660 = 5,280 feet.

This decision wasn’t arbitrary. It reconciled existing land surveying practices with older traditions. Surveyors had long used chains—specifically Gunter’s chain, developed by Edmund Gunter in 1620—which measured 66 feet and fit evenly into both the furlong (10 chains) and the mile (80 chains). Adopting 5,280 feet preserved compatibility with these tools and methods.

“Standardizing the mile at 5,280 feet was less about scientific precision and more about bureaucratic pragmatism—it kept the land records consistent.” — Dr. Alan Prescott, Historian of Science and Measurement

A Timeline of Mile Development

The journey from Roman pacing to the modern statute mile spans nearly two millennia. Here's a concise timeline showing key milestones:

- 29–23 BCE: Romans introduce the *mille passus*, approximately 4,850 modern feet.

- 5th–10th Century CE: Post-Roman Europe sees fragmented use of miles; England uses variable local standards.

- 13th Century: Edward I promotes standardization but stops short of defining a national mile.

- 1593: English Parliament legally defines the mile as 8 furlongs (5,280 feet).

- 1620: Edmund Gunter introduces the surveyor’s chain, reinforcing the 66-foot chain and 660-foot furlong system.

- 1959: International agreement standardizes the foot as exactly 0.3048 meters, fixing the mile at 1,609.344 meters globally.

Why Not 5,000 Feet? The Practical Compromise

Given the Roman precedent, one might expect the mile to remain at 5,000 feet. But the shift to 5,280 reflects a deeper tension between tradition and practicality. While 5,000 would have aligned better with classical ideals, it clashed with England’s agrarian measurement framework.

The furlong was central to land ownership and taxation. Changing its length would have disrupted property records, maps, and legal documents. Instead of overhauling the entire system, lawmakers chose to extend the mile slightly to accommodate eight full furlongs. This ensured continuity in surveying and reduced resistance from landowners and officials.

In essence, 5,280 feet wasn’t chosen because it was elegant—it was chosen because it worked within an already entrenched system.

| Mile Type | Length in Feet | Region/Use |

|---|---|---|

| Roman Mile | ~4,850 | Ancient Rome, military roads |

| London Mile | ~5,000 | Medieval England, urban areas |

| Statute Mile | 5,280 | England (1593), later international standard |

| Irish Mile | 6,720 | Ireland until 19th century |

| Nautical Mile | 6,076 | Maritime navigation, based on Earth's circumference |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why don’t we switch to the metric system?

Many countries have adopted the metric system, including the kilometer (1,000 meters) as the standard distance unit. However, the United States, Liberia, and Myanmar still primarily use miles. Cultural inertia, infrastructure costs, and public familiarity contribute to the continued use of miles in everyday contexts like driving and athletics.

Is the mile used anywhere besides the U.S.?

Yes. The United Kingdom officially uses kilometers for road signs but retains miles in common speech and legislation. Canada uses kilometers nationally, but many older citizens still reference miles informally. Additionally, international aviation and maritime industries use nautical miles, which are different from statute miles.

How accurate was Gunter’s chain?

Edmund Gunter’s 66-foot chain, composed of 100 links, was remarkably accurate for its time. It allowed surveyors to measure large plots efficiently and consistently. Its design directly supported the 5,280-foot mile by making calculations divisible and repeatable—proving that good engineering can shape measurement policy.

Conclusion: A Number Shaped by History

The number 5,280 may seem random, but it’s actually a product of historical negotiation between Roman legacy, agricultural practice, and English law. More than just a figure, it represents centuries of human effort to quantify space in ways that serve society. From Roman soldiers marching in step to surveyors laying chains across open fields, the mile evolved not through theory, but through necessity.

Understanding why a mile is 5,280 feet offers more than trivia—it reveals how culture, politics, and practicality shape even the most basic elements of our world. The next time you see a mile marker or complete a 5K run, remember: you're engaging with a tradition nearly 2,000 years in the making.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?