The abbreviation \"lb\" for pound is so familiar that most people use it without questioning its origin. Whether you're reading a nutrition label, weighing produce, or tracking your fitness goals, \"lb\" appears consistently across contexts. Yet, unlike other units such as \"kg\" for kilogram or \"oz\" for ounce, \"lb\" doesn’t seem to match the word “pound.” So why is this the case? The answer lies deep in linguistic history, stretching back over two millennia to ancient Rome.

To understand why \"pound\" is abbreviated as \"lb,\" we must trace the evolution of weight measurement through Latin, Roman commerce, medieval trade practices, and the adaptation of symbols into modern typography. This journey reveals not just a quirk of language but a testament to how deeply classical civilizations have influenced contemporary life—even in something as mundane as unit abbreviations.

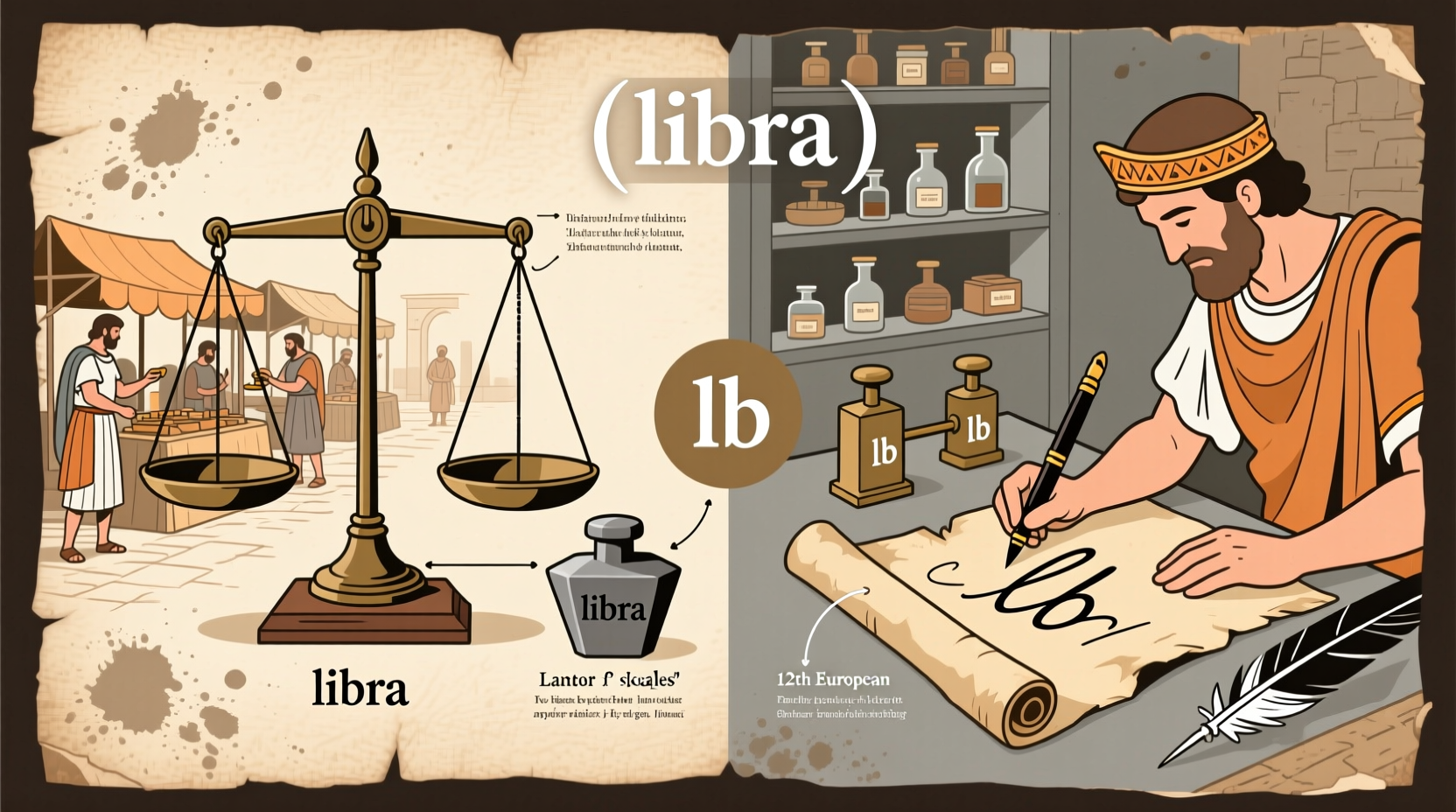

The Latin Roots: Libra and the Roman Weight System

The abbreviation \"lb\" comes from the Latin word libra, which means \"balance\" or \"scales.\" In ancient Rome, libra was also the term for a unit of weight roughly equivalent to 327 grams—close to today’s avoirdupois pound (453.6 grams). The Romans used a standardized system for trade, and the libra pondo (“a pound by weight”) was a common measure.

Breaking down the phrase: “pondo” meant “by weight,” while “libra” referred to the balance scale used to measure goods. Over time, “pondo” became associated with the weight itself, evolving into the English word “pound.” However, the symbol retained the initial from libra, not “pondo.” Thus, \"lb\" preserves the legacy of the instrument of measurement rather than the noun describing the quantity.

“Language carries history in its abbreviations. 'Lb' is a living relic of Roman metrology still used daily around the world.” — Dr. Elena Martinez, Historical Linguist, University of Cambridge

Medieval Adaptation and the Spread of lb

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, much of Europe continued using variations of Roman measurement systems. During the early Middle Ages, Charlemagne attempted to standardize weights and measures across his empire, reinforcing the use of Roman-derived units. Manuscripts from monasteries and merchant records frequently used \"lb\" as shorthand for libra in accounting and trade ledgers.

By the 12th century, the term had entered Old French as *livre*, which also meant both a unit of currency and weight. Although the French livre as a monetary unit eventually disappeared, its symbolic representation persisted in written form. English traders adopted many of these conventions, especially after the Norman Conquest, further entrenching \"lb\" in commercial documentation.

Crucially, scribes and bookkeepers favored brevity. Writing out full words was time-consuming, so abbreviations like \"lb,\" \"oz\" (from *uncia*), and \"dr\" (*dram*) became standard. The lowercase \"l\" with a horizontal stroke through it (℔) was often used in manuscripts to denote libra—a practice that gradually simplified to \"lb\" with the rise of printing in the 15th century.

Standardization in Trade and Science

As international trade expanded during the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods, consistency in measurement grew increasingly important. While different regions maintained local definitions of the pound—ranging from 373 grams in Venice to over 500 grams in parts of Germany—the abbreviation \"lb\" remained remarkably consistent in notation.

The British Imperial system, formalized in the 19th century, defined the avoirdupois pound as exactly 7,000 grains or 0.45359237 kilograms. Despite this precise definition, the symbol stayed rooted in tradition: \"lb\" was already entrenched in legal documents, scientific texts, and commercial invoices. Changing it would have caused confusion and resistance.

In contrast, newer metric units introduced in France after the Revolution were designed with rational prefixes and symbols (e.g., kg, g, mg), reflecting Enlightenment ideals of clarity and universality. But even as the metric system gained global traction, \"lb\" endured in countries resistant to full metrication—particularly the United States, Liberia, and Myanmar.

A Comparative Look: Units and Their Symbols

Understanding \"lb\" becomes clearer when compared to other measurement abbreviations. Many originate from Latin terms, preserving historical roots rather than phonetic spelling:

| Unit | Abbreviation | Origin | Original Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pound | lb | Latin: *libra* | Balance or scales |

| Ounce | oz | Italian: *onza* (from Latin *uncia*) | One-twelfth part |

| Inch | in | From Latin *uncia* | Twelfth of a foot |

| Pennyweight | dwt | From Latin *denarius* | Ancient Roman coin |

| Hundredweight | cwt | Latin: *centum pondus* | Hundred pounds |

This table illustrates a broader pattern: many English measurement symbols are derived not from the modern word, but from their classical ancestors. Like \"lb,\" they reflect centuries of linguistic continuity in science, commerce, and everyday life.

Real-World Example: Grocery Labeling and Global Confusion

Consider a typical grocery store in the United States. A package of ground beef might be labeled “1.5 lb” — instantly recognizable to American consumers. But an international visitor might find this confusing, expecting “pd” or “pnd” instead. Meanwhile, the same product in Canada displays both “1.5 lb” and “680 g,” highlighting the coexistence of imperial and metric systems.

In one documented case, a U.S.-based online retailer shipped products to Europe using only “lb” on packaging, leading to customer complaints about unclear labeling. After analysis, the company added metric equivalents and briefly experimented with “pounds” spelled out—but reverted due to space constraints and brand familiarity. Ultimately, they kept “lb,” adding a footnote explaining the abbreviation. This real-world scenario underscores how historical abbreviations remain functionally dominant despite potential ambiguity.

Common Misconceptions About lb

Several myths surround the origin of \"lb\":

- Misconception: \"LB stands for 'lead weight' because early scales used lead.\"

- Reality: There's no etymological link between \"lb\" and lead (whose chemical symbol is Pb, from Latin *plumbum*).

- Misconception: \"It’s short for 'London pound,' referencing British standards.\"

- Reality: While Britain standardized the pound, the symbol predates national standards by over a thousand years.

- Misconception: \"The slash through 'ℓb' means 'pound per...'\"

- Reality: The barred 'l' (℔) was simply a scribal abbreviation, not a unit modifier.

These misconceptions reveal how unfamiliarity with Latin-based abbreviations can lead to creative but inaccurate explanations.

FAQ

Why isn't 'pound' abbreviated as 'pd' or 'pnd'?

Because the abbreviation derives from the Latin *libra*, not the English word “pound.” Historical usage took precedence over phonetic logic, and \"lb\" was already standardized in European writing long before modern English fully developed.

Is 'lb' used outside the United States?

Yes. Countries like the UK, Canada, and Australia still use \"lb\" informally, especially in contexts like body weight or informal market pricing, even though the metric system is official. Road signs may show speed in km/h, but someone might say they weigh “150 lb.”

Does the plural change the abbreviation?

No. Whether singular or plural, the abbreviation remains \"lb.\" For example, “He weighs 180 lb” is correct; “lbs” is commonly seen but technically redundant since abbreviations of units don’t pluralize in formal writing.

Conclusion: Embracing the Legacy of lb

The abbreviation \"lb\" for pound is far more than a typographical oddity—it’s a direct line connecting modern society to ancient Rome. Every time you see \"lb\" on a recipe, a gym machine, or a shipping label, you’re encountering a fragment of Latin embedded in daily life. Its persistence speaks to the power of tradition in measurement, where practicality and historical continuity outweigh the urge for linguistic consistency.

Understanding the origin of \"lb\" enriches our appreciation of language and history. It reminds us that even small symbols carry layers of meaning forged over centuries of trade, scholarship, and human connection.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?