The fact that the three interior angles of any triangle add up to exactly 180 degrees is one of the first mathematical truths many people encounter in geometry class. It’s often presented as a given—something to memorize rather than explore. But behind this simple rule lies a deeper understanding of space, lines, and logic. Understanding why triangles behave this way not only strengthens your grasp of geometry but also reveals how mathematics builds consistent systems from foundational principles.

This article unpacks the reasoning behind the 180-degree rule for triangles using accessible explanations, logical proofs, and practical insights. Whether you're revisiting high school geometry or seeking clarity on a long-accepted fact, this breakdown will help you see triangles—and Euclidean space—in a new light.

The Role of Parallel Lines and Transversals

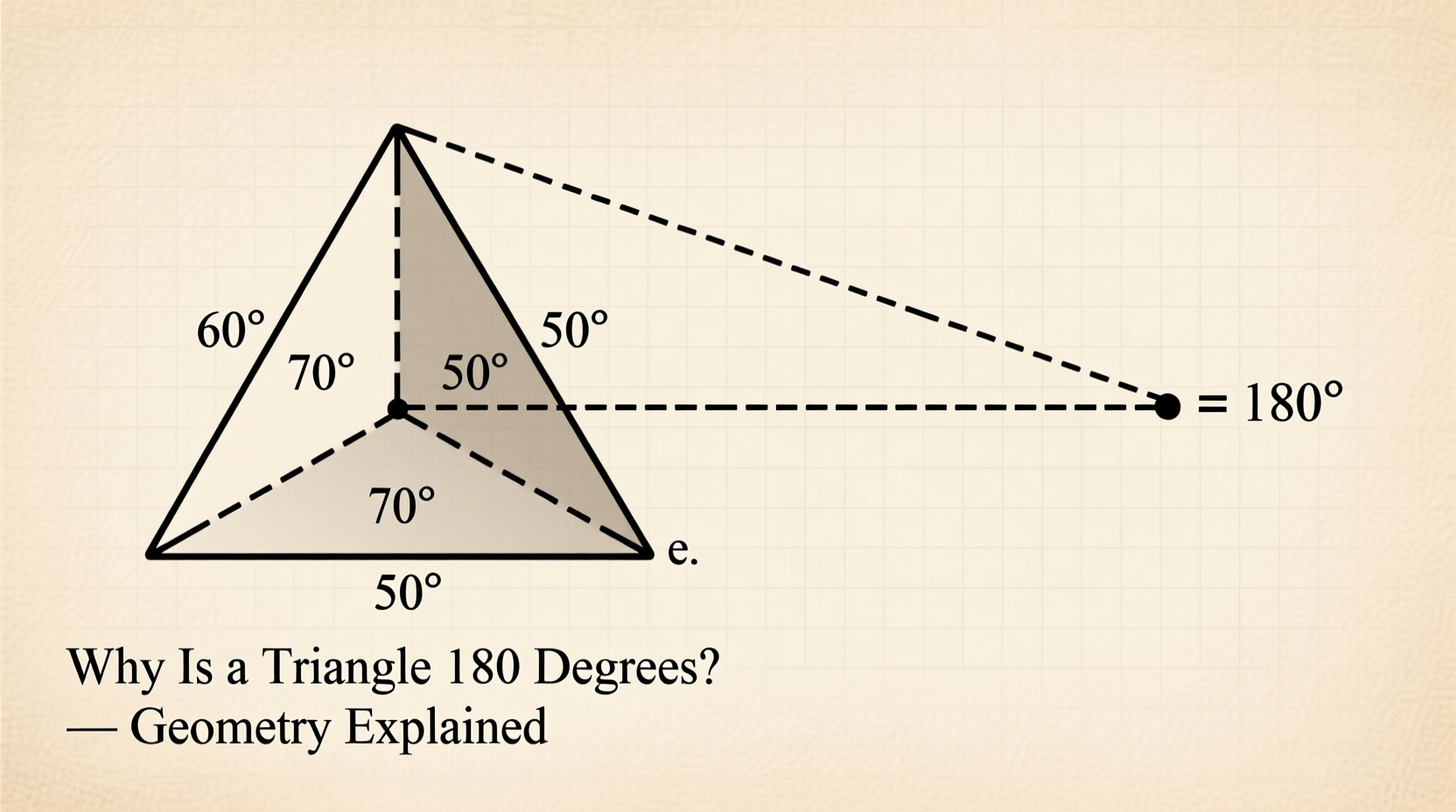

The key to understanding why a triangle’s angles sum to 180° lies in the properties of parallel lines and transversals. When two parallel lines are intersected by a third line (a transversal), several angle relationships emerge: corresponding angles are equal, alternate interior angles are congruent, and consecutive interior angles are supplementary (they add up to 180°).

To apply this to a triangle, imagine drawing a line through one vertex of the triangle that is parallel to the opposite side. This construction allows us to “slide” the other two angles over to sit adjacent to the third angle, forming a straight line—which, by definition, measures 180 degrees.

A Step-by-Step Geometric Proof

Let’s walk through a classic proof that demonstrates why the sum of the interior angles of a triangle equals 180 degrees. Consider triangle ABC, with vertices A, B, and C.

- Draw triangle ABC with base BC.

- Construct a line through point A that is parallel to side BC.

- Extend sides AB and AC past point A so they intersect the parallel line, forming two new angles outside the triangle.

- Label the angle at A as ∠A, the angle at B as ∠B, and the angle at C as ∠C.

- Because the constructed line is parallel to BC and AB acts as a transversal, the alternate interior angle formed at the intersection with the parallel line equals ∠B.

- Likewise, since AC is another transversal, the alternate interior angle on the other side equals ∠C.

- Now, observe the three angles meeting at point A: the original ∠A, plus the two transferred angles equal to ∠B and ∠C.

- These three angles lie on a straight line—therefore, their sum must be 180°.

- Hence, ∠A + ∠B + ∠C = 180°.

This proof doesn’t depend on the type of triangle—scalene, isosceles, equilateral, or right-angled. As long as we’re working within Euclidean geometry (flat planes), the result holds universally.

Euclidean vs. Non-Euclidean Geometry: When Triangles Break the Rule

An important nuance often overlooked is that the 180-degree rule applies specifically to flat, two-dimensional surfaces known as Euclidean planes. In non-Euclidean geometries—such as spherical or hyperbolic spaces—this rule no longer holds.

On a sphere, for example, consider a triangle formed by starting at the North Pole, traveling down the Prime Meridian to the equator, moving along the equator one-quarter of the way around Earth, then returning to the North Pole. Each corner of this triangle forms a 90° angle. The total? 270°—well over 180°.

In contrast, in hyperbolic geometry (a negatively curved space), the sum of a triangle’s angles is always less than 180°. These exceptions highlight that the 180-degree sum isn’t a universal law of nature, but rather a consequence of the assumptions built into Euclidean geometry—particularly the parallel postulate.

“Geometry is not just about shapes; it's about the underlying assumptions we make about space.” — Dr. Evelyn Reed, Mathematician and Geometry Educator

Real-World Applications of Triangle Angle Sums

Understanding why triangles sum to 180° has practical implications far beyond textbooks. Architects use this principle when designing roof trusses, ensuring load distribution aligns with angular stability. Surveyors rely on triangulation methods to map land accurately, knowing that measured angles must conform to geometric rules to detect measurement errors.

In navigation and astronomy, angular sums help verify observations. If three sightlines form a triangle and their angles don’t sum to approximately 180° (accounting for minor error margins), it may indicate instrument miscalibration or atmospheric distortion.

Mini Case Study: Detecting Errors in Land Surveying

A civil engineering team was mapping a triangular plot of land using theodolites. They recorded angles of 58°, 61°, and 60°—summing to 179°. Recognizing that the total should be 180° in flat terrain, they rechecked their instruments and discovered a slight misalignment in one device. After recalibrating, the corrected measurements were 58.5°, 61°, and 60.5°, totaling exactly 180°. This small correction prevented future layout errors in construction planning.

Common Misconceptions About Triangle Angles

Several misunderstandings persist about triangle angle sums. Clarifying these helps reinforce true comprehension:

- Misconception: All triangles have a right angle.

Truth: Only right triangles do. Most triangles are acute or obtuse. - Misconception: The 180° rule works on all surfaces.

Truth: It fails on curved surfaces like spheres or saddles. - Misconception: You need to measure all three angles to know the third.

Truth: Knowing two angles lets you calculate the third via subtraction from 180°.

| Triangle Type | Angle Sum | Surface |

|---|---|---|

| Equilateral | 180° | Flat (Euclidean) |

| Spherical Triangle | Greater than 180° | Curved (e.g., Earth) |

| Hyperbolic Triangle | Less than 180° | Negatively Curved Space |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a triangle have more than 180 degrees?

Yes—but only if it's drawn on a curved surface like a sphere. In standard flat-plane (Euclidean) geometry, no triangle can exceed 180 degrees. On a globe, however, large triangles can have angle sums reaching nearly 540° under extreme conditions.

Why does folding a triangle’s corners make a straight line?

This hands-on classroom demonstration works because each interior angle is physically aligned next to the others. When placed together without gaps or overlaps, they form a straight angle—180°—visually confirming the mathematical rule. It’s a tactile version of the parallel-line proof.

Does the size of the triangle affect the angle sum?

No. Whether the triangle spans millimeters or kilometers, as long as it lies on a flat plane, its internal angles will always sum to 180°. Scale does not impact angular relationships in Euclidean geometry.

Actionable Tips for Teaching and Learning Triangle Angles

- Practice estimating missing angles in triangles before calculating them.

- Use protractors to measure angles in hand-drawn triangles and verify the sum.

- Explore paper-folding activities where students cut out triangle corners and align them on a straight edge.

- Compare results on flat paper versus a balloon or ball to introduce non-Euclidean ideas.

- Encourage questioning: \"What if we changed the surface?\" to spark deeper inquiry.

Conclusion: Embrace the Why Behind the Rule

The reason a triangle’s angles sum to 180 degrees is not arbitrary—it emerges logically from the structure of parallel lines and the nature of flat space. By exploring the proof, recognizing its limits in non-Euclidean contexts, and applying it practically, we move beyond rote memorization to genuine understanding.

Mathematics thrives when we ask “why” instead of accepting facts at face value. The next time you see a triangle, remember: its angles form a perfect half-turn, a harmony of lines and logic rooted in centuries of geometric thought.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?