Alcohol is one of the most widely consumed psychoactive substances in the world. Unlike many illicit drugs, it’s socially accepted, legally available, and deeply embedded in cultural rituals. Yet despite its normalization, alcohol has a powerful grip on the human brain—one that can lead to dependency, compulsive use, and long-term health consequences. The question isn't just whether alcohol is addictive, but *why* it holds such a strong influence over behavior. Understanding the neuroscience behind alcohol addiction reveals how this substance hijacks the brain’s reward system, alters neurochemistry, and rewires decision-making processes over time.

The Brain’s Reward System and Dopamine Release

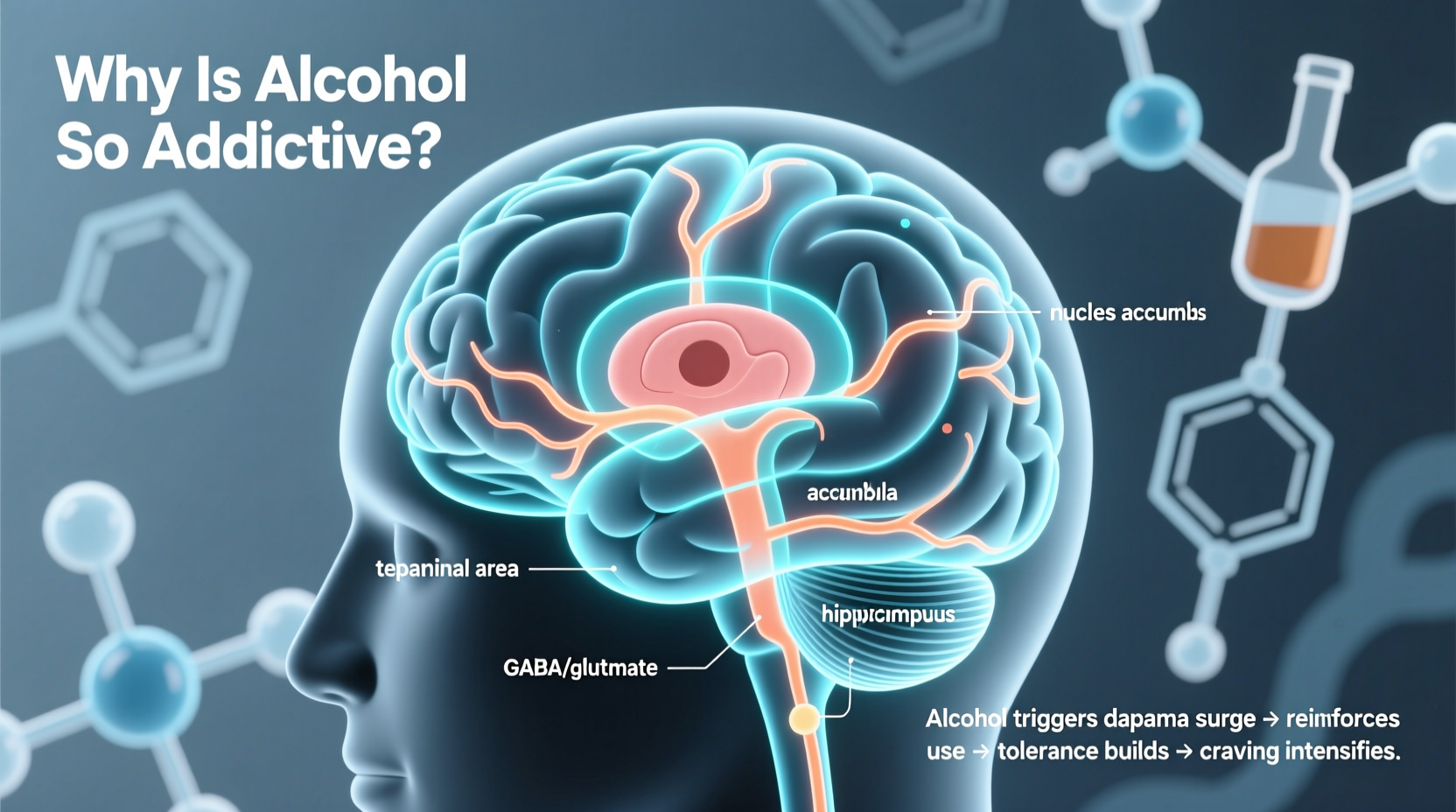

At the heart of alcohol’s addictiveness lies the brain’s reward circuitry, primarily governed by the neurotransmitter dopamine. When alcohol enters the bloodstream and reaches the brain, it stimulates a surge of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens—the region associated with pleasure, motivation, and reinforcement of behaviors. This flood creates a sense of euphoria, relaxation, or confidence, depending on the individual and context.

What makes this process particularly dangerous is its similarity to other addictive substances like nicotine or opioids. The brain begins to associate alcohol consumption with positive outcomes, reinforcing the behavior through a feedback loop. Over time, the brain learns to crave alcohol not for intoxication alone, but as a shortcut to feeling good. This conditioning becomes stronger with repeated use, especially when drinking occurs during stressful or emotionally charged situations.

Neuroadaptation and Tolerance Development

With regular alcohol use, the brain adapts to maintain balance—a process known as neuroadaptation. It responds to the constant presence of alcohol by reducing natural dopamine production and altering receptor sensitivity. GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), which calms neural activity, becomes less effective because alcohol mimics its effects. Simultaneously, glutamate, the brain’s primary excitatory neurotransmitter, increases in response to alcohol’s depressant action, leading to hyperexcitability when alcohol wears off.

This adaptation results in tolerance: more alcohol is needed to achieve the same effect. But it also sets the stage for withdrawal symptoms when drinking stops. These can range from mild anxiety and tremors to severe complications like seizures or delirium tremens. The discomfort of withdrawal drives many individuals to continue drinking—not for pleasure, but to avoid feeling unwell. At this point, addiction shifts from being reward-driven to relief-driven.

“Alcohol doesn’t just alter mood—it remodels the brain’s wiring. Chronic use impairs prefrontal cortex function, weakening impulse control and judgment.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Neuroscientist at Boston Addiction Research Institute

Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors

Not everyone who drinks develops an addiction, and genetics play a significant role in vulnerability. Studies show that up to 50–60% of the risk for alcohol use disorder (AUD) is hereditary. Specific gene variants affect how quickly alcohol is metabolized and how strongly the brain responds to its effects. For example, people with certain polymorphisms in the *ADH1B* and *ALDH2* genes experience unpleasant reactions like flushing and nausea, which naturally protect against heavy drinking.

However, environment often determines whether genetic predisposition manifests into actual addiction. Childhood trauma, chronic stress, social isolation, and peer pressure all increase the likelihood of problematic drinking. Adolescents are especially vulnerable; their brains are still developing, particularly the prefrontal cortex responsible for self-regulation. Early exposure to alcohol can disrupt normal development and increase lifelong addiction risk.

| Risk Factor | Impact on Addiction Likelihood |

|---|---|

| Family history of AUD | Doubles to triples risk |

| Early onset of drinking (before age 15) | Increases risk by 4x |

| History of trauma or PTSD | Strongly correlated with binge drinking |

| Social environments where drinking is normalized | Encourages habitual use |

| Mental health disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety) | Common co-occurring conditions; may lead to self-medication |

Breaking the Cycle: A Step-by-Step Guide to Recovery

Recovery from alcohol addiction is challenging but entirely possible with the right approach. The brain’s plasticity allows it to heal and rewire itself after prolonged abstinence. Here’s a practical, evidence-based timeline for breaking free from alcohol dependence:

- Recognize the problem: Acknowledge patterns of increased tolerance, failed attempts to cut down, or continued use despite negative consequences.

- Seek medical evaluation: Especially if drinking heavily, consult a healthcare provider before quitting cold turkey due to seizure risks.

- Detox under supervision: Medically managed detox can ease withdrawal symptoms using medications like benzodiazepines or anticonvulsants.

- Engage in therapy: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) helps identify triggers and develop coping strategies. Motivational Interviewing enhances commitment to change.

- Build support systems: Join groups like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), SMART Recovery, or online communities to reduce isolation.

- Adopt healthy routines: Exercise, sleep hygiene, and nutrition stabilize mood and reduce cravings.

- Monitor progress: Use journals or apps to track sobriety milestones and emotional states.

Real-Life Example: From Dependence to Long-Term Sobriety

James, a 38-year-old project manager, began drinking socially in college. By his early 30s, he found himself having wine every night to cope with work stress. What started as two glasses grew to half a bottle, then a full one. He noticed he felt irritable and fatigued on weekends unless he drank. After missing a family event due to a hangover, he decided to stop—but experienced insomnia, anxiety, and intense cravings within days.

He reached out to a therapist specializing in addiction and entered a short-term outpatient program. With CBT, he identified his stress triggers and learned mindfulness techniques. He replaced evening drinking with running and joined a local recovery group. Two years later, James remains sober. “I didn’t realize how much control alcohol had until I tried to let go,” he says. “Now I feel present in my life again.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Can moderate drinking turn into addiction?

Yes. While moderate drinking doesn’t guarantee addiction, it can escalate, especially in high-risk individuals. Life changes like job loss, divorce, or illness can shift casual use into dependency. Regular monitoring of drinking habits is essential.

Is alcohol more addictive than other substances?

Addiction potential depends on multiple factors, including method of use, frequency, and individual biology. Alcohol is highly addictive due to its widespread availability, social acceptance, and potent effect on both reward and inhibition systems. Its legal status often masks its danger compared to illicit drugs.

How long does it take for the brain to recover after quitting alcohol?

Some improvements begin within weeks—better sleep, clearer thinking, stabilized mood. Structural brain recovery, including regrowth of gray matter volume, can occur within 6–12 months of sustained abstinence. However, full cognitive restoration varies by duration and severity of past use.

Action Plan: Reducing Alcohol Dependence

- Track your drinking for one week using a journal or app

- Set clear limits or consider a dry month to reset tolerance

- Replace drinking occasions with alternative activities (e.g., coffee dates, walks)

- Talk to a doctor or counselor about concerns

- Remove alcohol from your home to reduce temptation

- Practice saying no confidently in social settings

- Explore underlying emotional reasons for drinking

Conclusion: Taking Back Control

Alcohol’s addictiveness stems from its profound impact on the brain’s chemistry, structure, and function. It exploits natural reward pathways, dulls emotional pain temporarily, and gradually undermines autonomy. But awareness is power. By understanding the science of addiction, recognizing personal risk factors, and taking deliberate steps toward change, it’s possible to regain control. Whether you’re seeking to reduce consumption or pursue full recovery, the journey begins with a single choice—to see alcohol clearly, not just socially, but biologically.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?