Body Mass Index (BMI) has long been a cornerstone in public health and clinical medicine for evaluating weight relative to height. While not a direct measure of body fat or overall health, BMI serves as a practical screening tool that helps identify potential weight-related health risks. In an era where obesity rates continue to rise globally, understanding the importance of BMI—and its limitations—can empower individuals to make informed decisions about their health.

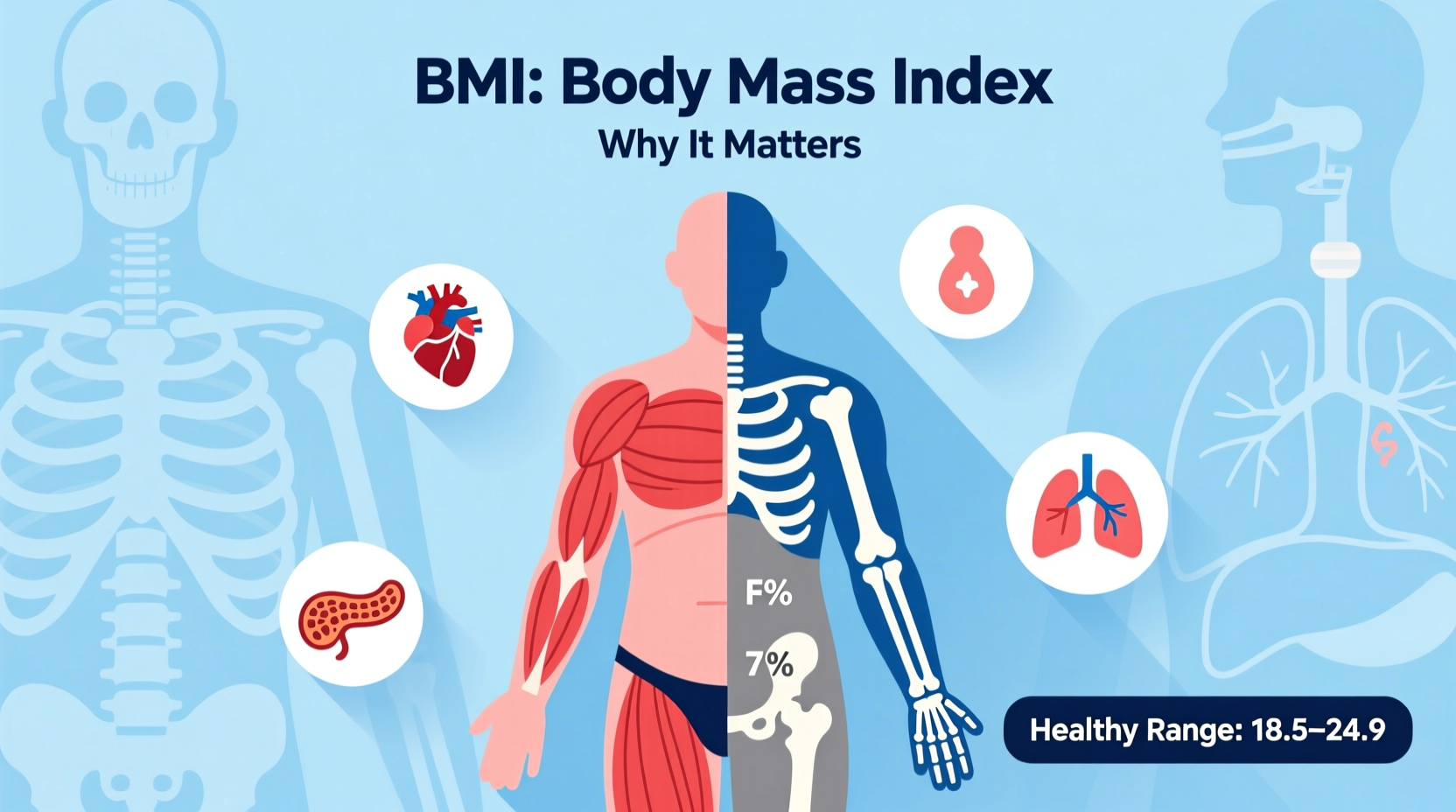

BMI is calculated using a simple formula: weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m²). Despite its simplicity, this metric provides a standardized way to categorize individuals into underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese groups. These categories correlate with varying degrees of health risk, making BMI a valuable starting point in conversations about weight management and preventive care.

How BMI Reflects Health Risk

One of the primary reasons BMI remains widely used is its strong correlation with certain chronic conditions. Research consistently shows that higher BMI values are associated with increased risks of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, sleep apnea, and some cancers. For example, individuals with a BMI in the obese range (30 or above) are statistically more likely to develop insulin resistance and elevated cholesterol levels than those within the normal range (18.5–24.9).

This does not mean that every person with a high BMI will develop these conditions, nor that someone with a \"normal\" BMI is free from risk. However, BMI acts as an early warning system—a red flag that prompts further investigation. A high BMI may lead a healthcare provider to order blood tests, assess waist circumference, or evaluate lifestyle factors such as diet and physical activity.

“While BMI doesn’t tell the whole story, it’s a useful population-level tool for identifying individuals who may benefit from deeper metabolic evaluation.” — Dr. Linda Chen, Preventive Medicine Specialist

Limitations of BMI: What It Doesn’t Measure

Despite its utility, BMI has well-documented limitations. It does not differentiate between muscle mass and fat mass, which can lead to misclassification. For instance, a professional athlete with high muscle density may have a BMI in the overweight or obese range despite having low body fat and excellent cardiovascular health. Conversely, someone with a “normal” BMI but high visceral fat (fat around internal organs) could still face significant metabolic risks—a condition sometimes referred to as \"skinny fat.\"

BMI also fails to account for fat distribution, which is critical in assessing health risk. Abdominal fat, particularly around the waist, is more strongly linked to heart disease and insulin resistance than fat stored in the hips or thighs. This is why waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio are often used alongside BMI for a more complete picture.

BMI Categories and Their Health Implications

The standard BMI classifications, established by the World Health Organization (WHO), provide a general framework for interpreting results:

| BMI Range | Category | Associated Health Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Below 18.5 | Underweight | Nutritional deficiencies, osteoporosis, weakened immunity |

| 18.5 – 24.9 | Normal weight | Lowest average risk of weight-related diseases |

| 25.0 – 29.9 | Overweight | Moderately increased risk of heart disease, diabetes |

| 30.0 and above | Obese | High to very high risk; may require medical intervention |

These ranges apply primarily to adults aged 18 and older. They are less accurate for children, pregnant women, older adults with muscle loss, and certain ethnic groups. For example, people of Asian descent tend to experience higher health risks at lower BMI levels, prompting some countries to adopt lower thresholds for overweight classification.

Real-World Application: A Case Study

Consider Maria, a 42-year-old office worker who visits her doctor for a routine check-up. At 5'5\" and 165 pounds, her BMI calculates to 27.4—placing her in the overweight category. She feels healthy and exercises moderately but has noticed occasional fatigue and elevated blood pressure readings at home.

Her doctor uses the BMI result as a conversation starter, recommending blood work that reveals prediabetes and elevated LDL cholesterol. With this information, Maria begins a structured program involving dietary changes, increased physical activity, and regular monitoring. Over six months, she loses 12 pounds, brings her BMI down to 25.3, and normalizes her blood sugar and blood pressure.

In this case, BMI was not the sole diagnostic tool but served as a critical trigger for early intervention—preventing progression to full-blown diabetes and reducing long-term cardiovascular risk.

Using BMI as Part of a Broader Health Assessment

To maximize its value, BMI should never be used in isolation. A comprehensive health assessment includes:

- Waist circumference measurement

- Blood pressure and lipid profile

- Fasting glucose or HbA1c levels

- Physical activity levels and dietary habits

- Mental health and sleep quality

Healthcare providers increasingly adopt a holistic approach, combining BMI with other markers to avoid stigmatizing patients based on weight alone. The goal is not to achieve a specific number on the scale, but to improve metabolic health, mobility, and quality of life.

Action Plan: How to Use Your BMI Wisely

If you’ve recently calculated your BMI or received it during a medical visit, here’s how to respond constructively:

- Don’t panic over the number. Remember, BMI is a screening tool—not a diagnosis.

- Assess your overall lifestyle. Are you physically active? Do you eat whole foods? How’s your stress level?

- Measure your waist. Stand and place a tape measure around your abdomen just above the hip bone. Breathe out and record the number.

- Consult a professional. A doctor or registered dietitian can interpret your BMI in context and recommend next steps.

- Set realistic goals. Focus on sustainable habits like walking daily or reducing added sugars, rather than rapid weight loss.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is BMI accurate for everyone?

No. BMI may misclassify muscular individuals, older adults with low muscle mass, and people of certain ethnic backgrounds. It should always be interpreted alongside other health indicators.

Can I be healthy with a high BMI?

Yes. Some individuals with higher BMIs exhibit normal blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels—often referred to as \"metabolically healthy obesity.\" However, long-term studies suggest they may still face elevated risks over time.

Should I rely on BMI to track weight loss progress?

It can be one tool among many. For better insight, combine BMI with measurements like waist size, body composition analysis (if available), and how your clothes fit. Progress isn’t solely defined by numbers.

Conclusion: Taking Control of Your Health Journey

Understanding why BMI is important means recognizing its role as a starting point—not the final word—in assessing health. It offers a quick, accessible way to gauge whether your weight might be impacting your long-term well-being. When combined with other clinical and lifestyle data, BMI becomes part of a smarter, more personalized approach to prevention and care.

Instead of viewing BMI as a judgment, use it as motivation. Whether you’re aiming to maintain a healthy weight or make meaningful changes, small, consistent actions add up. Talk to your healthcare provider, set achievable goals, and focus on building habits that support lifelong vitality.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?